I dreamed of a ruined laboratory. Inside the ruins, a single machine still worked: a device that could diagnose and fix whatever was wrong with your eyes. As I put my face up to the machine, my right eye was seized. I watched it being corrected by the device’s many small arms that manoeuvred tiny tools. As the machine slowly made my eye mechanical, the eye became the central image of the dream. The transformation was unsettling but not painful nor frightening. Instead, I seemed to anticipate the conversion. When it was complete, my eye looked the same, but I could feel that something had changed. I was told I could now see things more clearly.

I dreamed this eye-correcting dream one night in 2016 while living in Johannesburg, South Africa. I had come to research how this post-apartheid city was being transformed as it attempted to shed or redevelop the material infrastructure of its segregated past. It was during this research that I came upon fafi, a popular and informally regulated street-based lottery game played throughout the townships and urban areas of South Africa. The game is played by around 100,000 gamblers each day, primarily low-income Black South Africans on street corners throughout Johannesburg. Fafi, I would discover, is not a minor phenomenon. The Impact of Illegal Lotteries (2019), a report put out by a South African municipal government, suggests that fafi’s monthly turnover in one province alone is somewhere around 25 million rand (1.6 million US dollars) even though the average daily bet is only around R2 ($0.13). But what does any of this have to do with dreams of ruined laboratories and machine-corrected eyes?

Fafi is a game of chance, but playing it well involves more than simply choosing the right number, it requires careful interpretation of your dreams and the world around you. Through fafi, images from waking life and the world of dreams blur. The significance of a dream is equally weighted with a chance waking encounter – each produces meaningful data points through which a player can interpret winning numbers. What fafi offers is a way of thinking about how we interpret, calculate and anticipate the world.

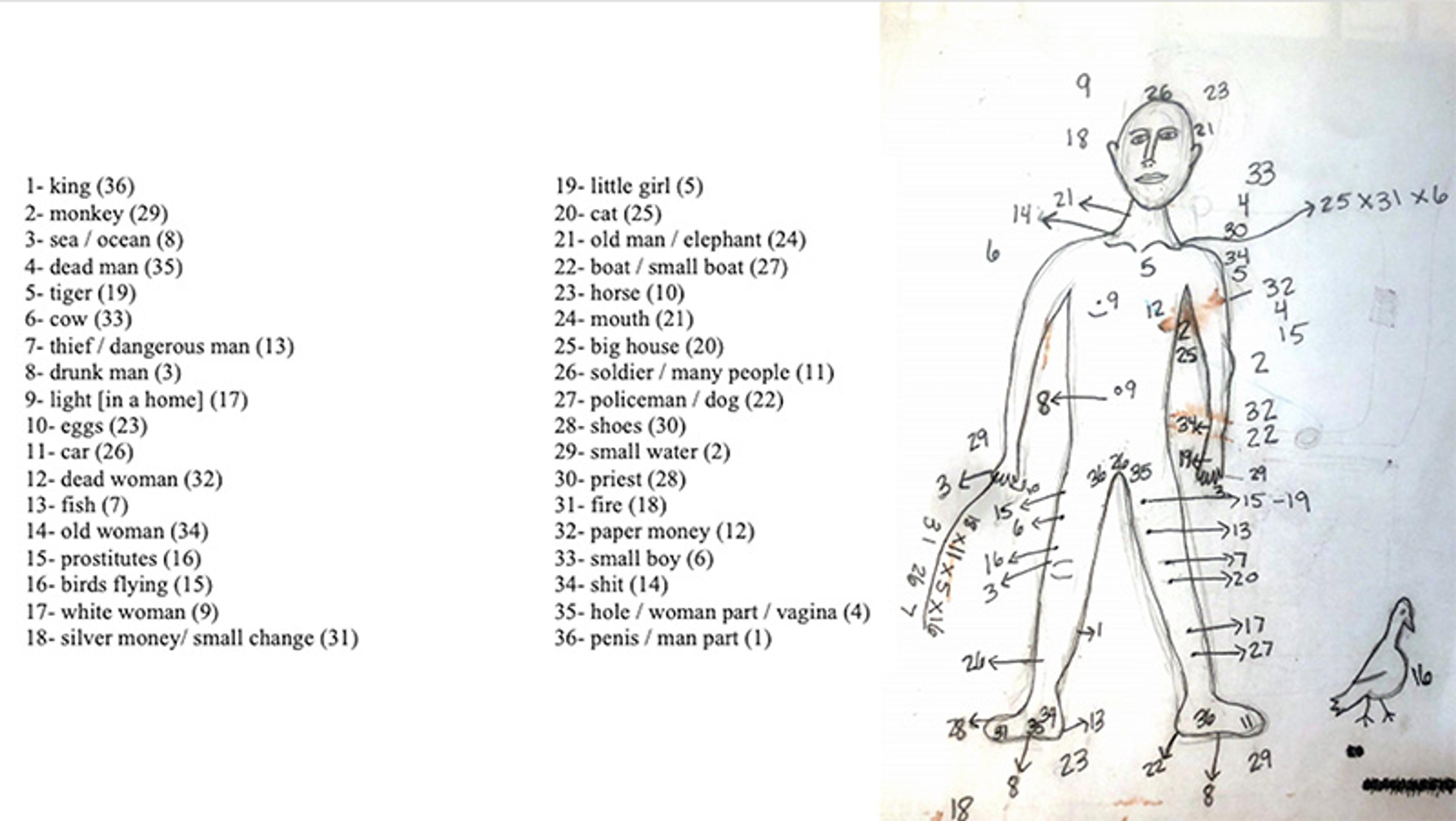

The mechanics of the game are simple: it’s a lottery with 36 possible winning numbers. To play, gamblers bet on one of those numbers, which each correspond to a particular image or figure. These images range from the seemingly mundane (shoes, eggs, cat, car, birds flying) to the more sinister (dead woman, fire, police, thief, drunk man). One winning number is selected each time. For every R1 bet, winners receive a different amount depending on whether they’ve pooled their bets: if they are a serious gambler and betting ‘in their own bag’, they’ll receive R28 in return; if they are betting in someone else’s bag, they’ll receive only half that.

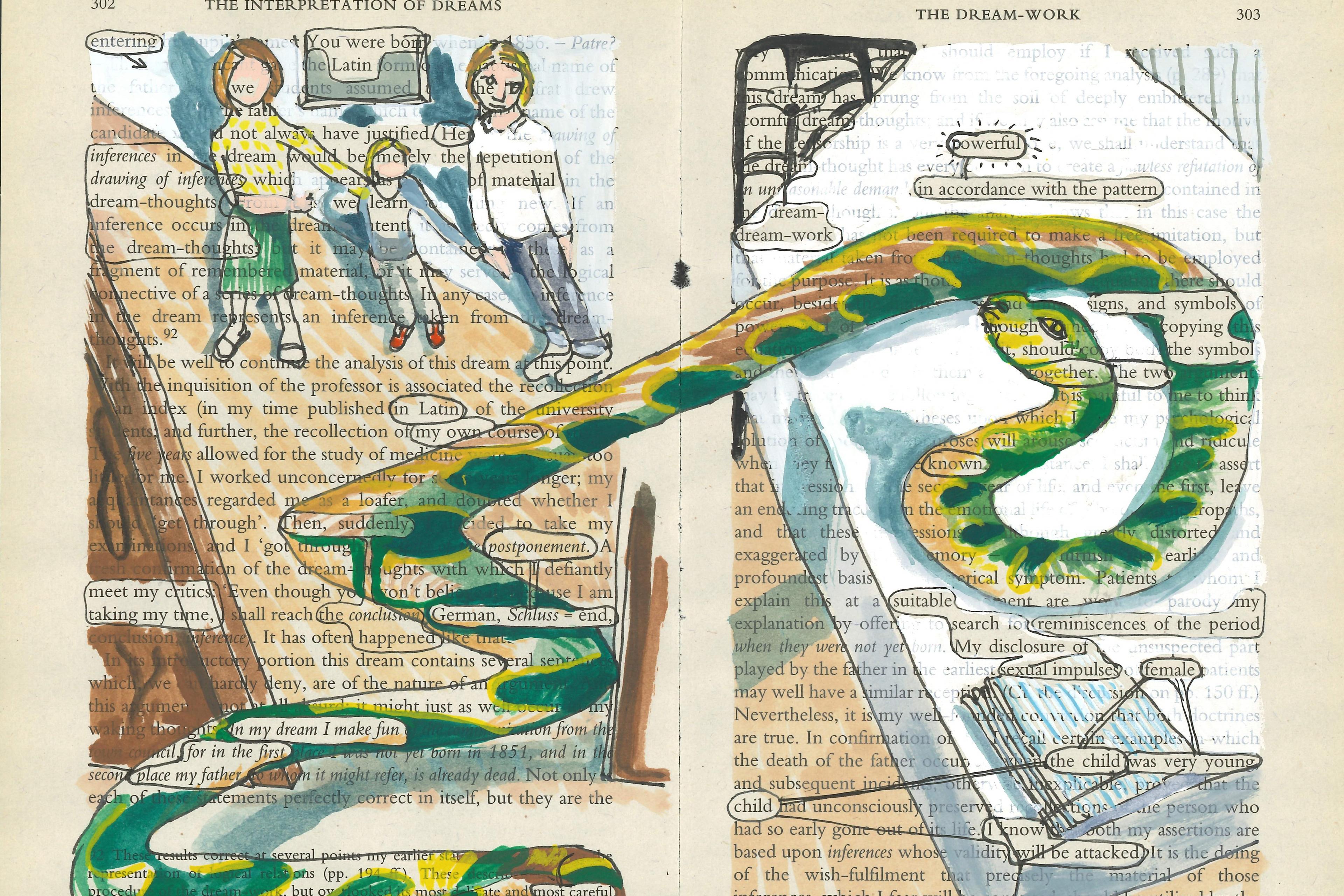

Image supplied by the author

From these simple basics, fafi quickly becomes complex through the cultural practices that surround it, including the way numbers are picked, the sites where gambling takes place, the placing of bets and the relationship between gamblers and those who run the game. These practices have evolved since the game became established in the 1930s. The precise origin of fafi is unknown, but it has ties to the Chinese community in South Africa, and these ties are rumoured to have connections to the Chinese mafia and Chinese migrants who arrived in South Africa in the early 1900s.

The winning number is announced, or rather performed, in real time to a group of dedicated players on street corners across the city. The game I participated in has taken place for many years on a corner in Jeppestown, a neighbourhood just east of central Johannesburg. It has a morning and an afternoon ‘pull’ – when the winning fafi number is revealed by the ‘fafi man’ who delivers it in person by driving from spot to spot in a large truck with bulletproof windows (necessary to prevent robberies). There are always two people in the truck, and they approach the ‘bank’ – the designated spot where gamblers have assembled – only once the local manager (the ‘head runner’) of the fafi game arrives. In every pull I observed, all bets are finalised and bags collected by the runner before the truck arrives. Once the runner is in place, the fafi man approaches in his truck. The bags with bets and money wagered are exchanged for a small slip of paper with the winning number written on it. Then, the runner stands before the assembled gamblers and performs a gesture that correlates to one of the 36 numbers. Upon seeing the gesture, whispers of the winning number, cries of excitement or frustrated sighs can be heard among the players.

After a winning number is pulled in one gambling site, there’s a collective understanding that it will not be pulled again at that site for the next two days. If you know the last number pulled, the odds of a win slightly increase – but there are other ways to ‘get ahead of the fafi man’. The relationships between numbers and their correspondence to different images make up the cosmology of fafi. Within this web of meaning is a set of strategies used to divine what a player should bet on next.

There are many strategies for choosing numbers to bet on, but the most common is the interpretation of dreams. Through fafi’s elaborate number scheme, dream images become wagers in the next game once they’ve been transformed into numerals through interpretation. But fafi is not only about dreams being taken seriously. In the game of fafi, everything has the potential to be interpreted through the number scheme – everything can be interpreted like a dream.

One Sunday, at the park where my local fafi game was played, I watched a large dance competition. Another woman who played fafi, and who knew I had become interested in the game, grabbed me by the arm and pointed to the people who surrounded us. ‘Many people,’ she whispered in my ear. ‘Number 26.’ The image before me, of men in costumes performing dances and many more seated or standing to watch the performance, was to be interpreted as a sign of how to bet the following day. Images from dreaming and waking life were to be weighed alongside one another. What fafi offers is a way of thinking about how we interpret, calculate and anticipate the world – through the game and its strategies, we see a model for engaging the world and its meaning, one that encompasses our conscious and unconscious states.

To truly engage in fafi, one must freely share one’s dreams and experiences. Withholding details from a dream or failing to interpret correctly is believed to directly correspond to the money, or lack of money, in one’s gambling bag. The question remains though, how do players interpret their dreams? And how do they know which dreams to take seriously? Did my eye-changing machine mean anything?

Johannesburg is not the only place where gamblers bet on dream images. The prevalence of lottery games tied to images and dreaming is a phenomenon across the globe: la smorfia in Naples, Italy; hua-hui across China; and ‘the numbers’ in the US. In each iteration, dreams serve as guides for navigating a variety of variables – charts, patterns, number sequences or events of waking life – deemed significant for divining the near future, the winning bet.

The South African journalist and author Ufrieda Ho has written about her childhood as the daughter of a fafi man, which was not a prestigious position in the Chinese South African community during apartheid. It remains a precarious position today. Ho depicts her father, who was seen as a kind of gangster, moving between the worlds of her suburban Chinese community to the inner city and townships where Black South Africans congregated to witness him delivering the winning number. In her memoir Paper Sons and Daughters: Growing up Chinese in South Africa (2011), she writes in detail about the different processes of num ju (the practices of thinking up the winning fafi number) and cheow ju (recording the numbers of each of the players at the different banks):

Occasionally my dad could not settle on the number he wanted to play and then he would call on Lady Luck with everything from throwing a few dice to folding up pieces of paper with possible good numbers and then selecting a random number from the small origami of folded squares. But even when he did this, it was not all random; it was as if chance and luck had to be part of the perfect recipe to guide him to the right number to play. Sometimes we were asked about our dreams and my mother also told what she had dreamt about. Those dreams were meant to spark something meaningful for my father as he sat and tapped his feet, sucked hard on a cigarette and worked through the record books again; sometimes there was just no way to connect a pattern of coincidence.

Just like the gamblers who take careful note of past winning numbers, construct extravagant number schemes and consult their dreams, the fafi man also attends to a series of calculations and rituals to make his decision. He is betting directly against the fafi players on the other side of this equation. But the two opponents, Ho writes, ‘needed each other’. It’s important to remember that economic inequality is worse today than during the apartheid regime. For those living at the edges of the new economic order in South Africa, fafi provides an opportunity to make extra money. But the odds, of course, favour the fafi man, and he is no doubt making a profit off the low-income gamblers. But, despite the dismal odds, fafi players continue to track the numbers and interpret their dreams. For better or worse, in many South African communities, fafi remains tightly woven into the fabric of daily life.

Fafi is a pure lottery. To place a bet, you must have your own bag or access to someone else’s – someone who is willing to take your bet. These bag-owners often work as informal interpreters of dreams and numbers, a position once allocated exclusively to sangomas, traditional Zulu healers and herbalists. To receive a bag, the runner of the fafi game you want to play must deem you a reliable player: someone who will calculate the bets in their bag correctly and play consistently. Because players earn more if they have their own bag, those who are serious about fafi have their own bag (or multiple bags). Serious players also keep careful records of ‘good numbers’. What makes a ‘good number’ is a confluence of signs that suggest the next winner. For this reason, talk of dreams circulates at the fafi bank.

While sitting at a fafi bank on a street corner, waiting for the runner to appear so that I could turn in my bag, a veteran player, Mama kaseBuko, requested that I share not only my numbers but my dreams, too. ‘Tell us your dreams,’ she said, ‘we play around you.’ After I recounted my eye-correcting dream, she smiled. ‘Eyes. We will bet on eye numbers,’ but she did not begin to list these numbers (1, 9, 18, 21, 23, 26). Rather, she asked the other women she organised bags with what they thought: were these good numbers? Were any of them already being played? My dream became an additional data point in approximating the winning number.

Dream interpretation was once the role of sangomas, but dreaming and its interpretation, along with the tracking of numbers and charts, is now cultivated at the fafi bank. However, the dream interpretation used by fafi players still retains some trace of the sangomas’ practices and their training of initiates. At times, the discussion of dreams and patterns at fafi banks resembles the kind of dialogue between trainee and teacher that takes place during preparation to become a sangoma.

Mama kaseBuko, in asking me to retell my dream, was attempting to train me, and she was not shy about letting me know my shortcomings as a gambler. ‘You have good numbers but bad money,’ she would tell me, disappointed that I was not investing more in the game. After our exchange, I waited at the bank until the white truck of the fafi man pulled around the corner. I watched the fafi bags being handed off and the performance of the gesture correlating to the winning number: 9. Associated with the image of ‘a light’, 9 is also closely associated with the head and eyes. I had won – as had all the women who had listened and bet on eye numbers, too. I ran into Mama kaseBuko a few days later after another number corresponding to eyes had won the morning pull. ‘The winning number was 1 today. You are lucky with your eyes,’ she said.

But what does this tell us about dreaming? It means that dreams are interpreted through dialogue, through exchange. It means that only in those moments of exchange can we comprehend their significance to waking life or determine how seriously to take them. My dream of the eye-correcting machine, which seemed impossible to tether to my waking life, became meaningful the moment it was solicited by Mama kaseBuko and recounted to the women at the fafi bank. It was a dream about learning to see, learning to think with dreams. It is only through engagement, a training of sorts, that one learns what dreams mean – and which dreams to bet on.