Nike has just released its first ever range of ‘mind-altering’ shoes. Its glitzy marketing campaign features a chief science officer, brain scan results and dramatic music. The shoes, which have an array of bobbles (sorry, ‘nodes’) on their soles, promise to help connect your body with your brain and tune you in to the present moment. I’m sceptical about the scientific claims, but I’m impressed by the storytelling.

In medicine, it’s well known that positive expectations about an intervention, even an inert one, can produce real physiological benefits – this is the placebo effect. As the neuroscientist and placebo expert Fabrizio Benedetti explained in his paper ‘Placebos and Movies: What Do They Have in Common?’ (2021) , it is the therapeutic rituals around a placebo treatment that magnify its effects. White coats, needles, pill colours, authoritative reassurance – all these factors can trigger associations that contribute to a patient’s belief that a treatment will work.

I’m reminded of Nathan Hill’s satirical novel Wellness (2023), in which the psychologist Elizabeth starts out investigating products that make dubious claims, but comes to realise the effects are real even if they’re purely a placebo. The key to their success is the ‘story surrounding the thing’, she observes; later, she becomes a consultant for multinational corporations, helping them to craft convincing fictions.

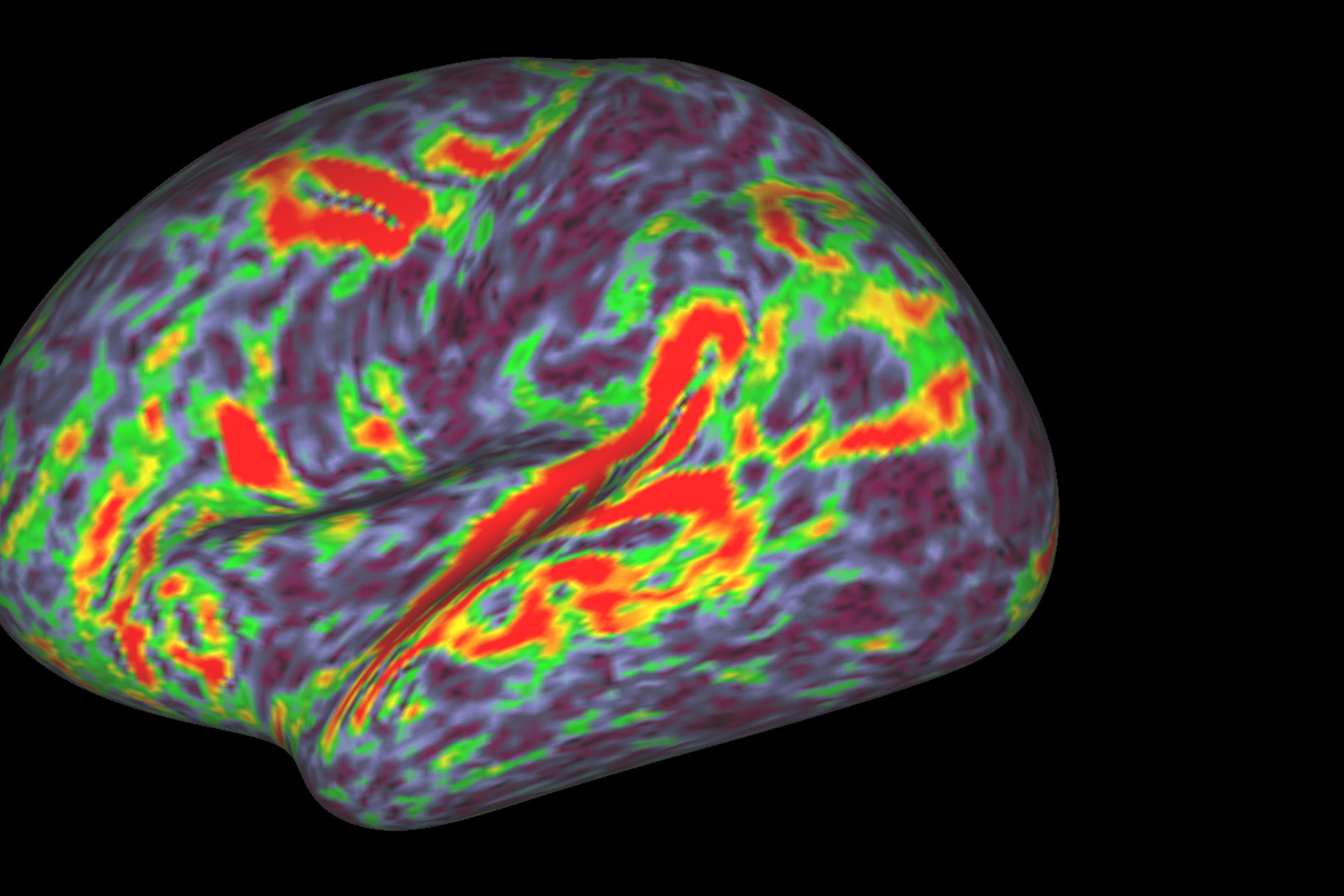

I suspect this is exactly what Nike has done with its new range of shoes. They’ve created an elaborate, compelling narrative tailored for an athletic audience looking to gain an edge: a ‘Mind Science Department’ staffed with neuroscientists who have developed shoes that ‘disengage the default mode network’ and engage the ‘sensorimotor network of the brain’. Is any of it real? The remarkable thing about the placebo effect – and Nike’s canny marketing exploits this fully – is that it doesn’t really matter.