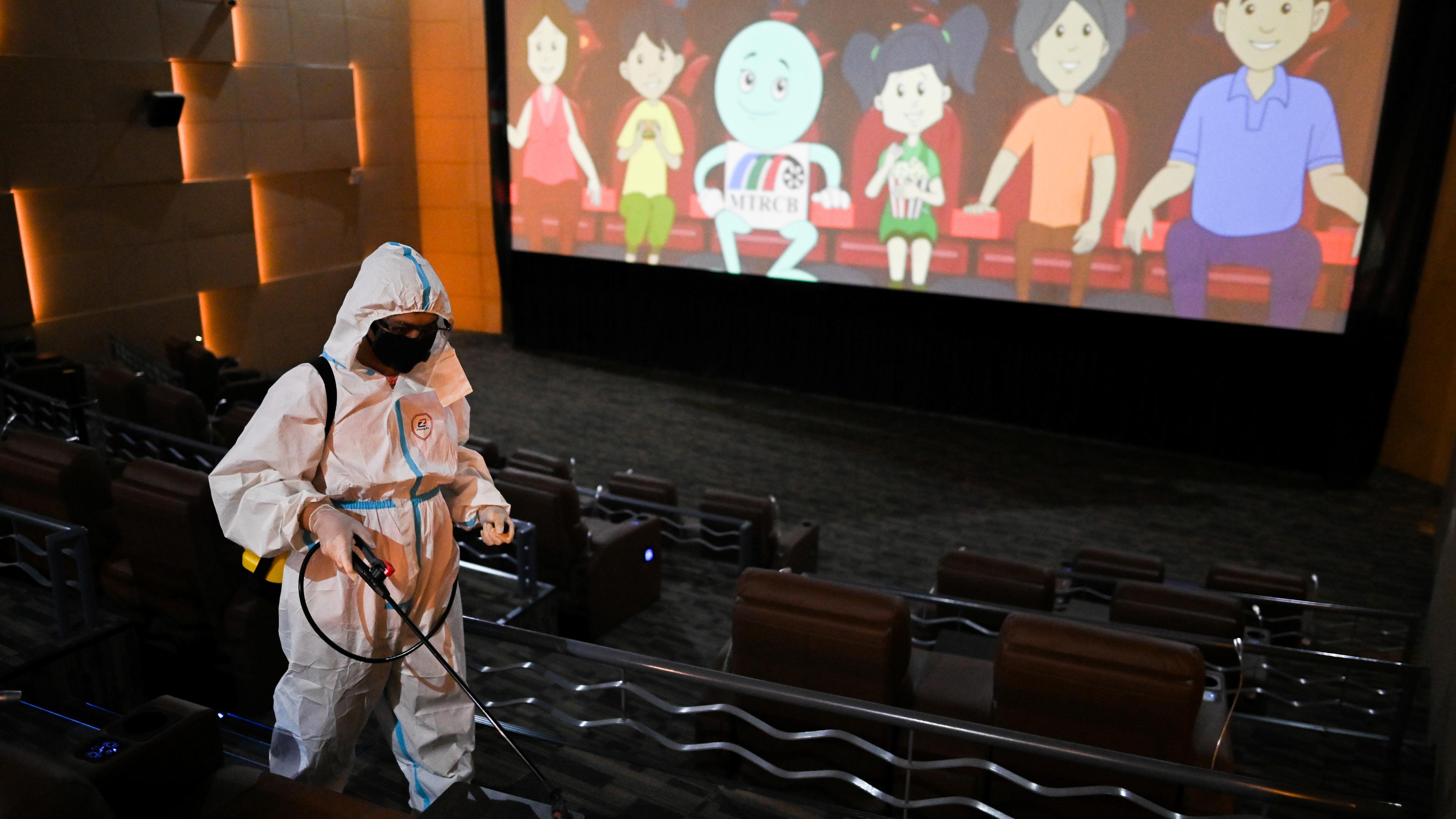

Mary is on her daily walk around the neighbourhood. Suddenly, she breaks into a fit of wheezing and coughing. Her chest feels constricted as she tries to regain her breath. She grabs a seat on a nearby bench to gather herself.

Now, I’ll add one last detail to the story: Mary is living in the year 2050. Her suffering is no different because of this fact. But perhaps it now feels a bit harder to empathise with her.

Warnings about the future peril facing humanity – which, of course, will be made up of specific people like Mary – are common these days, and for good reason. The harms of the climate crisis are poised to ramp up, while pandemics worse than COVID-19, threats of nuclear conflict, and safety risks from advancements in AI loom large. Experts estimate the odds of a catastrophe that kills at least one in 10 humans within a five-year span at 20 per cent this century – basically a roll of the dice. Yet most of the world remains insufficiently focused on mitigating the gravest threats to our species’ future wellbeing.

How should we balance our focus on immediate, shorter-term problems versus more gradually developing and future threats? It’s very difficult to say. But in a world where people could more easily empathise with future generations, public pressure to address those catastrophic risks would be greater. This, in turn, might lead to relevant safety policies moving closer to the front of political parties’ agendas. Government agencies that focus on such policies could receive much more funding to establish larger research teams and regulatory capacities for risk mitigation.

Public discourse has been gradually filling up with philosophical arguments and statistical information to marshal action to reduce the risks to our collective future. However, while presenting persuasive logic and convincing data is absolutely critical, it’s just not enough. To win the hearts and minds of policymakers and society at large, we also need to overcome emotional hurdles.

People reported less empathy toward the future sufferer (depending on how far in the future it was)

It’s already difficult for many of us to care about our future selves, let alone future generations. Many of us don’t save enough for retirement or exercise as much as we think we should, in large part because we find it hard to sufficiently empathise with the person we’ll eventually become. Present bias is pervasive. Passing the societal version of the marshmallow test may prove even more challenging, as it involves forms of favouritism that are both temporal (present vs future) and interpersonal (me vs you). In order to set humankind up for a flourishing future, we need to push against the psychological tendency to value our present selves far more than we value future others.

Other scholars have argued that there is no inherent moral distinction between someone’s suffering now or in the future. In a series of studies, David DeSteno and I recently investigated differences in how people actually feel when thinking about future versus present pain – and what, if anything, can be done to make future suffering more emotionally evocative.

We used a simple experimental design in which we randomly assigned participants to imagine a person suffering – from a respiratory disease, a broken ankle, etc – either in the present or at least 25 years in the future. Besides a brief description of the suffering (as in the case of Mary), participants weren’t told much else about this hypothetical person. We found that participants rated the amount of suffering the person experienced as nearly the same whether it was in the present or the future. However, when asked about their level of distress and concern, people reported 8 to 16 per cent less empathy toward the future sufferer (depending on how far in the future it was). That is, there was a mismatch between what people understood at an intellectual level (the amount of pain experienced by someone else) and their felt experience when imagining someone else’s suffering.

In everyday life, people often talk about future generations in a broader, more collective sense than we did in these studies. This introduces another pernicious computation of the mind: people find it easier to empathise with a single individual than with groups, plausibly because individuals are easier to conjure in one’s imagination. Therefore, the difference in empathy toward a present person and future others in general is likely even greater than what we’ve found.

Though empathy guides us to help others, psychologists have warned about how it drives us to preferentially help people we already know or who are similar to us, often at the expense of strangers or dissimilar others. Our findings illustrate that an empathy deficit applies not only across social and geographical distance, but across temporal distance, as well.

Does this empathy deficit matter, in practical terms? Yes, it does. We found that the lower level of empathy toward future others had real-world consequences. In one study, we framed the Clean Air Task Force, a nonprofit addressing climate change, as either helping people in the present day or helping people who will live 200 years from now. Compared with those who saw the present framing, those responding to the future framing donated 6 per cent less – and this difference was explained by reduced empathy. While this may seem like a small effect, the stakes are large when you consider the hundreds of billions donated to charity annually in the United States alone.

Promoting richer mental simulations of the future eliminated the empathy gap

Of course, supporting present-oriented causes isn’t a bad thing. There’s no lack of suffering from actively occurring problems that are worth addressing. Yet the effect of merely indicating that present (as opposed to future) people will benefit from a donation suggests a potential strategy for future-oriented nonprofits: if they emphasise their organisation’s benefits for people today, prospective donors should feel more empathy towards the beneficiaries and, in turn, be more willing to donate.

Fortunately, empathy is malleable. It can be redirected and expanded to those whom one might not naturally tend to care about very much. In our final study, we deployed a simple intervention that asked participants to imagine another person’s future suffering in vivid, concrete detail. Before reading about the suffering of someone like Mary, they were asked to take 30 seconds to imagine the situation in as much detail as possible, contemplating the expression on her face and any sounds she might make. We found that engaging in this brief exercise ramped up the study participants’ empathy for future others so that it resembled what they felt toward present others. In other words, promoting richer mental simulations of the future eliminated the empathy gap.

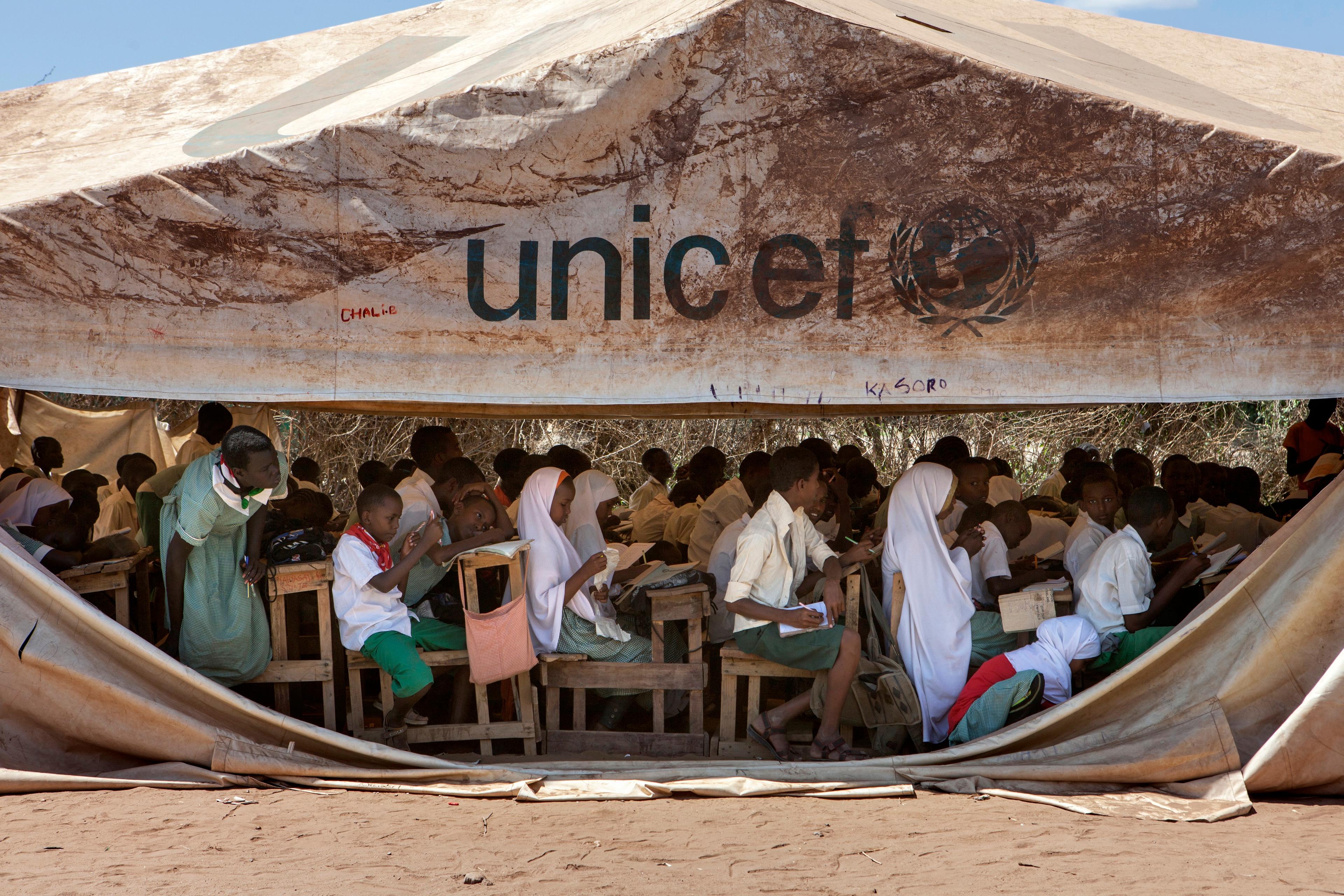

Communicators in many different professions could leverage this insight to motivate their audiences to help future generations (such as by donating to nonprofits or supporting political candidates who seriously address long-term global problems). Filmmakers and authors can ‘reel in’ the future, so to speak, by depicting relatable characters facing future problems in clear, vivid detail. Public officials can tell powerful stories to their constituents about the consequences of our present bias for the soon-to-be very real people inheriting the world we’ve left them. Experts on catastrophic risks can complement their data-driven science communication with emotionally engaging rhetoric of this kind.

This is a relatively new area of research, and there are many important unanswered questions. It’s conceivable that parents, for example, might feel more empathy for future people, given that they’re already invested in the future vis-à-vis their child’s wellbeing. Maybe the empathy deficit is less prevalent in cultures that explicitly value the welfare of future generations. Or, perhaps those who think major societal risks are imminent don’t require any more future-orientation, as their empathy for present people is already sufficient to get them to act. Further exploration of the impediments to empathising with future generations could inform other practical strategies for overcoming them.

Improving the quality of humanity’s future requires serious, significant action on the part of governments, businesses and everyday individuals. To inspire such action, we need to align economic incentives and deploy a healthy dose of political pressure. But let’s not neglect the importance of nudging the human mind. Coupled with sound evidence and well-reasoned logic, an enhanced level of feeling for the people of coming generations can give us the motivation we need to steer our collective future in the right direction.