To read someone’s intentions – or to know what they are feeling – we look instinctively into their eyes. In moments of negotiation or intimacy, we have an intuitive sense that the eyes convey more than their outward beauty. They offer something deeper, something unspoken yet powerful.

I am a psychologist and pupillometrist. I study the pupils – those small, seemingly black openings in the eye that expand and contract continuously. Research in my field shows the eyes really are a window into the psyche – in fact, they might be even more revealing than you realise.

You might have been taught that pupil-size changes are nothing more than a reflex response to changes in brightness. While it’s true that the pupils expand as it gets darker and constrict as brightness increases, they can give away much more information than that, subtly reflecting a person’s mental effort, their feelings – even the content of their imagination.

At a physiological level, the size of the pupil is determined by the two interacting muscles of the iris (the coloured part of the eye). These muscles are controlled by the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems – these are the two opposing branches of the body’s automatic control centre that manage relaxation and alertness, respectively.

Given this basic anatomy, perhaps the least surprising information revealed by the pupils is how awake someone is – their pupils will be smaller when they’re tired and larger when they’re wide awake. If you’ve ever looked into the bathroom mirror after a long tiring day, perhaps you have noticed how small your own pupils can be.

Any increase in mental effort, no matter how small, is accompanied by a measurable increase in pupil size

As well as revealing how awake someone is, their pupils can also tell you how intensely they are exerting mental effort. The Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman (re)discovered in the 1960s that the more digits a participant memorised, the larger their pupils became (I say rediscovered because a largely forgotten early literature anticipated many modern findings in this field). This effect isn’t bound to digits – any greater demand on memory will make the pupils dilate. The phenomenon is so reliable that it can be used to distinguish people based on their intelligence. For instance, if you give people arithmetic tasks of equal difficulty, those showing less pupil dilation (a sign of less mental effort) will be the ones who also tend to score higher on academic tests.

This connection between pupil size and mental effort is both sensitive and broad. Any increase in mental effort, no matter how small, is accompanied by a measurable increase in pupil size. Moreover, any kind of increased effort can cause the change – be that sexual interest, controlling body movements (or even just imagining making movements), being touched by others or experiencing intense emotions, such as surprise.

Perhaps even more remarkable is that changes in pupil size can reveal what a person is attending to mentally. This is because the pupil’s reflexive response to light can be triggered not only by what a person looks at directly, but also by what they are choosing to attend to with their mental spotlight (even if their gaze is directed elsewhere).

For instance, imagine staring straight ahead, but having a bright object such as a candle on one side of you, and a dark object such as a cup on the other. While keeping your eyes still, you can choose to attend covertly either to the candle or the cup. Your pupils will then respond to the attended brightness, without your eyes moving even a tiny bit – thus giving away where you are choosing to focus your mental spotlight.

But perhaps the most astonishing fact about pupil size is that it can reveal the content of a person’s imagination. In a 2013 study from the University of Oslo, participants imagined familiar scenarios, such as a bright sky, the sun, or a darkened room, all the while looking at the same grey background. Their pupils were smaller when imagining the bright scenes, compared with the dark scenes. This finding mimics a case report from the 1920s of a participant who lost his eyesight as a child, but who many years later was still able to recall the image of a glaring sun and, when he did so, his pupils became noticeably smaller.

When participants with aphantasia recalled the bright and dark shapes, their pupil sizes stayed unaltered

Because the pupils can give away what we’re imagining, this means they can also be used to study the vividness of a person’s mental imagery. A 2022 study focused on aphantasia, the self-reported inability to form visual imagery. Aphantasia is challenging to study for psychologists because it’s difficult to objectively verify a person’s subjective experiences. Are they truly unable to form imagery? Or do they simply label their imagery experiences differently than most other people?

Studying pupil size offers a brilliant way to explore these questions. In one task of the 2022 study that used a similar logic as the earlier research on the link between visual imagery and pupil size, participants with and without self-reported aphantasia first saw shapes of different brightnesses and later recalled these shapes while looking at an empty computer screen.

When the control participants recalled the shapes, the researchers saw they had a smaller pupil size when recalling the bright shapes than for dark shapes, suggesting that they were seeing the bright shapes in their mind’s eye. By contrast, when the participants with self-reported aphantasia recalled the bright and dark shapes, their pupil sizes stayed unaltered. This implies that they couldn’t visually reproduce the shapes and so there was no effect on their pupils. It’s as if their pupils were giving the researchers a window into the private world of their minds.

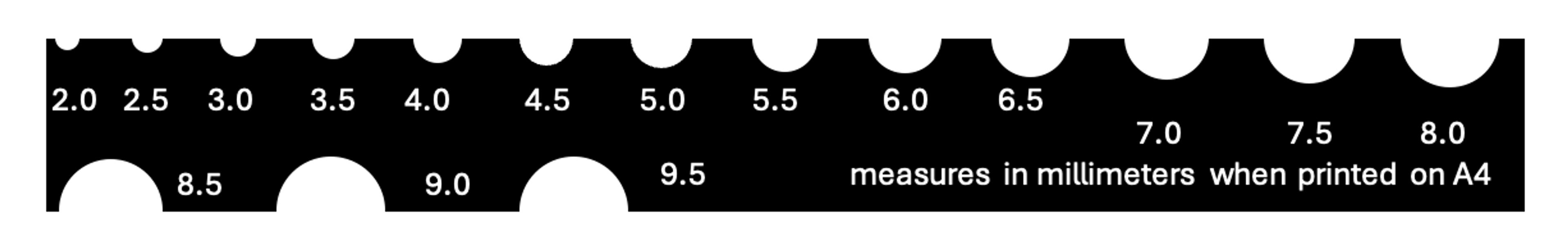

I hope I have convinced you that pupil-size changes are a fascinating marker of many aspects of the psyche. My academic peers and I study the finest pupil-size changes with expensive and specialised equipment. But if you’re intrigued to find out more, you can get started doing pupillometry with a very simple item of equipment called a Haab pupillometer.

With this and other simple tools, the Swiss ophthalmologist Otto Haab managed to measure pupil-size changes so well that he discovered the way that covert shifts in attention can affect the pupil’s light response – more than 100 years before its description by contemporary researchers. If you want to give it a try, the principle is easy:

- Print out the image below on A4 paper, then cut out the pupillometer as a rectangle (so make sure to leave the semi-circles in).

- Next, hold the basic pupillometer next to your participant’s eye (or your own eye if you are using a mirror). Select the half-circle that most closely matches your pupil size.

- Focus on a single spot with constant brightness and avoid blinking. Do this 10 times and measure your pupil size in each case. Take the average. This is your baseline measure.

- Now repeat: do the same another 10 times or so, but additionally perform some tricky mental calculations while you go along, such as multiplying the numbers 13 and 14, or 8 and 13. Write down all measurements (or ask a helper to write them down) and, again, take the average.

- Did you observe larger average pupil sizes for the calculation task than the baseline? If so, you just demonstrated the effect of mental effort on pupil size, replicating a 1964 paper in Science, using your own pupillometer.

Remember, changes might be subtle, but even minor pupil expansion reflects heightened mental effort. Congratulations, you’ve just joined the ranks of pupillometrists!

A Haab pupillometer; cut it out in a rectangle, then you can use the half circles as a way to measure pupil size

Even in the age of brain scans, pupillometry allows fascinating and even unique insights into our psyches. That’s why pupillometry is arguably more popular today than ever. Doing pupillometry is easy compared with brainscans. A brainscan is very expensive, participants can’t move in the scanner because it ruins the data, and data analysis is error-prone because of its high complexity. If the additional details a brainscan provides aren’t needed to answer a research question, an easier method such as pupillometry is therefore preferable.

Furthermore, pupil responses are quite reliable, meaning that one does not need to measure as long and you can still get good results. In fact, even some brainscan studies additionally measure the pupils because of this. The possibility to study what someone is imagining, and how vividly, is why I first fell in love with this field – that little dark opening to the eye really is a very special window.