In the film Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986) – the one with the whales – the crew of the USS Enterprise travels back in time and, of course, hilarity ensues as the familiar faces from the future try to blend in with the San Francisco of the 1980s. At one point, Scotty sits down to a (then state-of-the-art) Macintosh computer and tries to figure out how to get it to work. Frustrated, he picks up the mouse and holds it to his mouth like a communicator device, sassily asking: ‘Hello, computer?’ This is one of the funniest moments of the movie, solely because we the viewers know that the future world of Star Trek holds such fabulous technology as talking computers, while the 1980s of the film’s production held boxy, expensive machines that could barely run a word processor, let alone a whole spaceship.

Now, almost 40 years later, as I sit here writing this article, I have just asked my own version of the Enterprise computer to play that movie for me. Thank you, Siri.

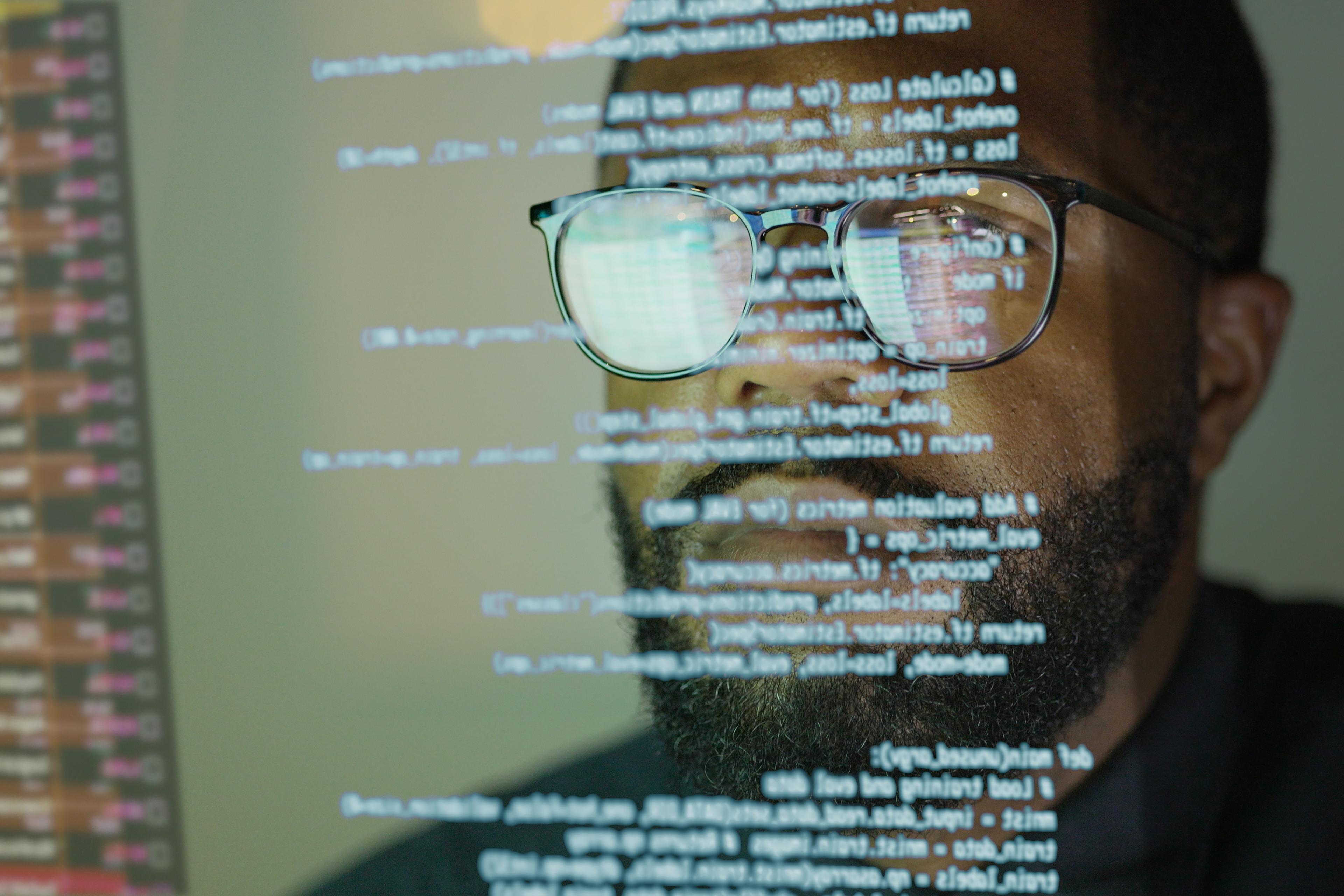

Siri, of course, wasn’t the first real voice-interactive computer to enter the popular consciousness. In early 2011, a team at IBM introduced Watson, the talking computer that defeated the champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter on the TV quiz show Jeopardy! Later that year, Apple introduced Siri for its iPhone 4S, a breakthrough in voice-interactive software. According to their creators, both Siri and Watson were directly inspired by Star Trek’s Enterprise computer. But, as with all cultural narratives, the path from science fiction to reality is a bit more circuitous than a scientist seeing a movie and saying: ‘I want to make that.’

Artificial intelligence itself is an illusion, one that comes straight out of science fiction. The term ‘artificial intelligence’ was first coined in 1955 by John McCarthy, then a mathematics professor at Dartmouth College, and his fellow mathematicians and computer scientists: ‘every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.’ In other words, AI is a simulation, a facsimile, of human intelligence. It’s basically the software version of René Magritte’s painting The Treachery of Images (1929), a representation of reality, rather than reality itself. Ceci n’est pas une pipe; ceci n’est pas une personne.

Likewise, media itself is an illusion. When you watch a movie, you’re watching the representation of people and props and sound, all recorded at a previous time and location. When image and sound are played together, it’s called synchronised sound, a process that’s designed to give the illusion of presence, or to make you feel like you’re really there with the people in front of you. For example, when you go to see the latest superhero movie, Chris Evans and Chris Hemsworth and all the other actors named Chris aren’t really in front of you. They’re off doing whatever they do with their time when not making movies. What’s in front of you is the illusion of their characters, all cut together and projected onto a screen using the magic of the movies.

Sometimes, however, you don’t see the character. Sometimes, there’s voiceover narration, or a disembodied character like the titular Wizard of Oz. In sound studies, we call this the acousmêtre, or the acousmatic character: a sound that one hears without seeing what causes it. The Great and Powerful Oz is great and powerful precisely because you see only the floating green head and hear only that booming voice. Once you look behind the curtain and see the body to which the voice belongs, the illusion of power disappears. He’s just a guy with a microphone and a smoke machine.

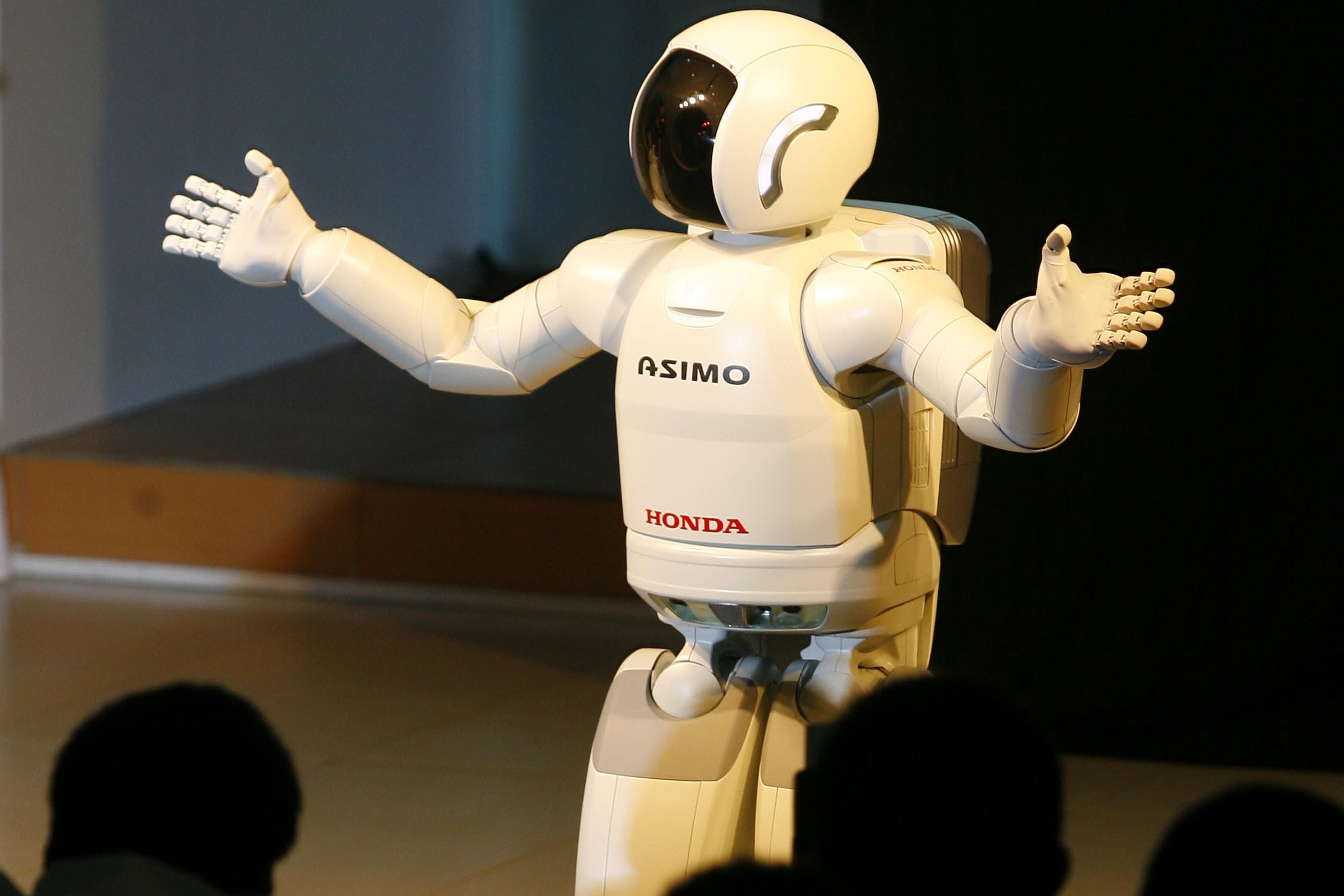

Talking computers, or ‘acousmatic computers’ as I call them in my book The Computer’s Voice (2020), work similarly, but there’s no body behind a curtain. The actor’s voice is recorded and then played over the image of a computer, creating the illusion of a living, talking computer like the Enterprise in Star Trek. Siri works exactly the same way: audio of a person’s voice emanates from your phone or watch or what have you, giving you the illusion of Siri’s presence in that computer object.

In fact, the first appearance of the Star Trek computer in the 1966 episode ‘Mudd’s Women’ shows an acousmatic computer doing exactly what Siri does for us now. Captain Kirk interrogates a notorious smuggler, Harry Mudd, by asking the ship’s computer to provide information from a networked database. Every command begins with ‘Computer’ just like we might say ‘Hey Siri’ today. The computer’s voice is mechanical and stilted, an auditory representation of the kind of clunky machines that really existed in the 1960s, somewhat reminiscent of the sound of old-timey phone operators. Behind the scenes, the Star Trek actress Majel Barrett recorded the lines of dialogue, the production crew shot the scene of Kirk and Mudd and the others sitting around a table talking to a little computer screen, and then it was all edited together to create the illusion of a talking computer.

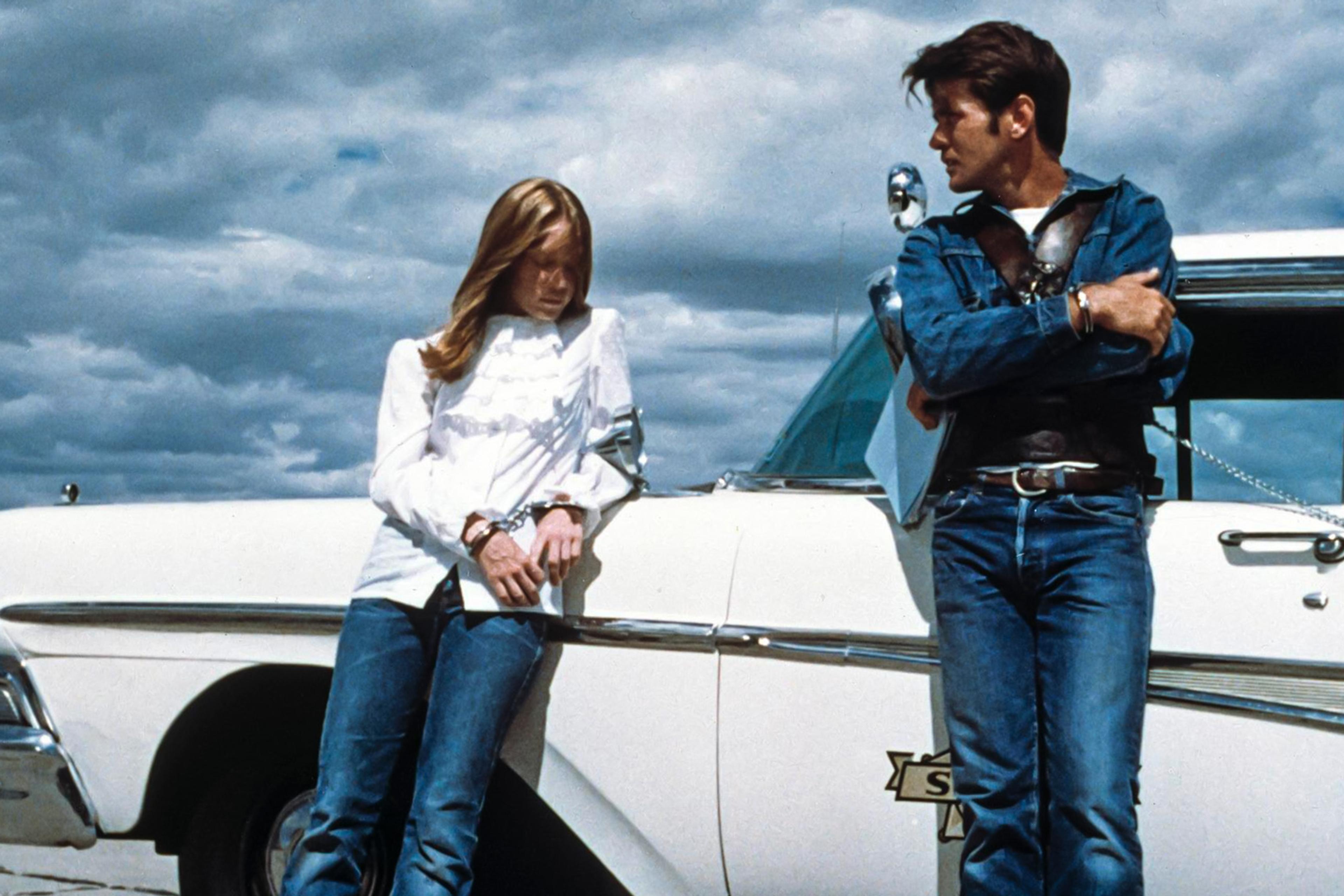

The choice of Barrett as the computer’s voice is an important one. Her voice is not mechanical like the synthesised speech of a Speak & Spell toy. She really does sound like a typical secretary of the 1960s, talking to her boss over an intercom. The portrayal of a talking computer in Star Trek is what sci-fi does best: take the culture and technology of the present and dream up future possibilities. Other fictional acousmatic computers – like HAL 9000 in Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) or, more recently, Samantha from Spike Jonze’s film Her (2013) – don’t have human bodies, but they do have genders and personalities, and often their roles in the narrative reflect human gender roles.

HAL, played by Douglas Rain, is a cold, murderous monster, and gendered male. Samantha, played by Scarlett Johansson, is a sassy personal assistant-turned-lover of a heterosexual man. When you hear Johansson’s voice, you’re able to immediately picture the feminine body from which the voice emanates, even though what you’re seeing on the screen as her ‘body’ is just a smartphone. These fictional roles are imbued with gender by the voices of the real actors, the pronouns used to describe their characters, and our cultural expectations of gender roles. After all, gender itself is a cultural practice: it’s not just how our bodies are shaped but also the way we dress, and talk, and interact with one another.

So science fiction just plonks a talking computer into a pre-established gender role like a secretary or a murderer or a lover, modelling for viewers how we can relate to our computers just like we relate to other humans. Thus, the production of Siri isn’t as simple as a scientist watching Star Trek and saying: ‘Cool, yes, I want my computer to talk to me like that.’ The mechanism of voice-interactive software relies on the cultural history of acousmatic computers in science fiction, on gender roles, on the magic of synchronised sound. Thank you, Computer.