When you think of the Renaissance, what comes to mind? Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel in Rome? The wealth and power of the Medici family in Florence? Humanist scholars busy digging up dusty manuscripts of the Greek and Latin classics in Alpine monasteries? Gutenberg’s press in Germany? Leonardo and linear perspective? Classicising architecture?

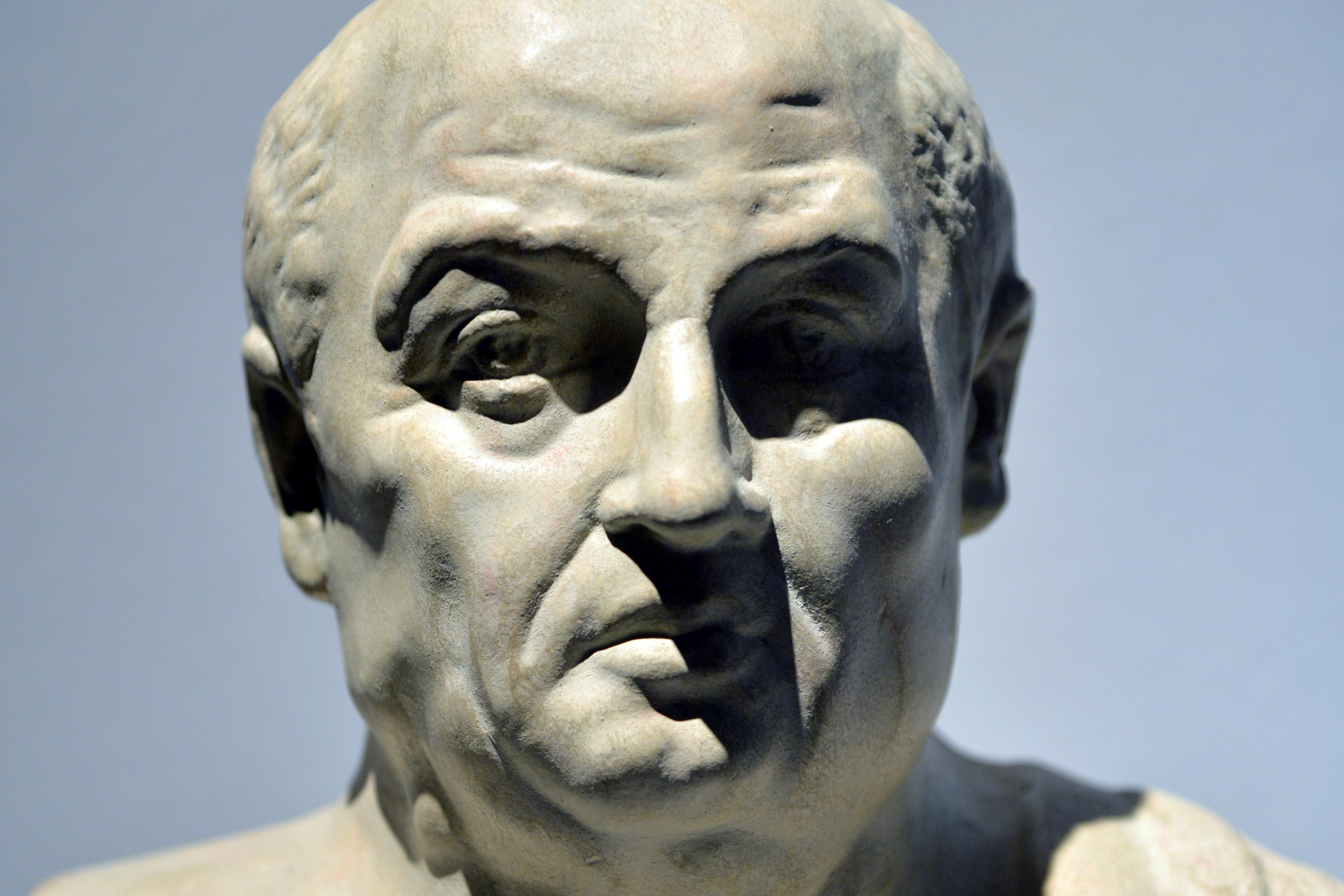

These are all part of the story, for sure. But I bet you’ve never heard of the Japanese-born Martinho Hara (原) (c1568-1629). This is a pity because not only did Hara’s life overlap with better-known Renaissance scholars such as Montaigne in France and Giordano Bruno in Italy, but he also shared many of their humanistic interests and standards. Perhaps the most surprising of these was that this Japanese Renaissance humanist was an accomplished Latin public speaker (or ‘orator’ to use the contemporary term). In other words, he was a Japanese echo of the Roman statesman and philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BCE), the Renaissance’s ‘poster boy’ whose speeches were widely imitated by diplomats, preachers and professors from the late 14th century onwards.

How did this happen? Born close to the thriving Luso-Japanese port of Nagasaki in Southern Japan, Hara studied with the Jesuits who had founded colleges across Asia and Latin America. This was facilitated by Iberian (ie, Spanish and Portuguese) mercantile and imperial expansion, which simultaneously ravaged the world’s coastlines and created new opportunities for cultural interactions on a global scale. In the Jesuit college in Nagasaki (as well as in the colleges of Mexico City, Puebla, Guadalajara, Lima, Manila, Goa, Macau, etc), students followed a typical Renaissance curriculum, including classical rhetoric: the rules for structuring and ornamenting speeches that had been key to elite education at Athens and Rome and were later revived in the Renaissance.

As a result of the widespread diffusion of classical rhetoric, although the floors of the Roman senate and Athens’s three courthouses had long since fallen silent, classicising public speaking in Latin, Spanish, Portuguese and other languages was common at funerals, civic festivals and academic events across the Iberian world. This was a highly versatile tool that could be put to any number of uses, from the imperialist to the humanitarian (and everything in between). Indeed, Hara’s only surviving oration is a great example of this versatility, as a speech that championed the Jesuits’ missionary project (thereby painting the European monarchs who supported them in a favourable light), while showing explicit concern for Japan’s fledgling Christian community.

Hara delivered his Latin oration in 1588 in the chapel of St Paul’s College in Goa during a stop-off in India on his return journey from the Tensho Embassy to Rome. In his speech, which was pronounced in a space that evoked antiquity with its Corinthian columns and gate reminiscent of a Roman triumphal arch, this Japanese Cicero thanked the head of the Jesuit mission in Asia, Alessandro Valignano, praising him as a new Alexander the Great, conquering Asia for Christ. As an epideictic oration (ie, a speech focused on either praise or blame, and commonly used in Roman imperial rituals), this was meant not just to celebrate its subject. Rather, it aimed to exhort its listeners to follow in Hara’s footsteps in spreading Christianity and countering its ‘enemies’ in Japan: Buddhism and Shintoism.

After some 20 minutes of eloquent Latin panegyric, Hara ended with words that left his listeners in no doubt as to his Christian fervour and genuine concern for the growing number of Japanese Christians:

So now advance into Japan with a great army of almost heavenly warriors, which you command; take the province by divine force; lay it low with virtue; rip our oppressed homeland from the hands of the savage enemy and restore it to true liberty! The Japanese call out to you and long for you, the wind is at your back, the seas are calm, the doors are open; see, beloved father! Do not delay! Advance!

After its delivery, Hara’s rousing speech was printed by another Japanese student on a press brought from Europe. This was later taken to Macau and Nagasaki, where it was used to print Latin textbooks for use by aspiring Chinese and Japanese priests. Clearly then, the Latin books, Ciceronian orations and classicising architecture that we associate with the Renaissance were found not just in famous European centres, such as Florence, Venice and Paris. Rather, the Renaissance was a widespread, almost global movement initially carried beyond Europe by Spanish and Portuguese expansion in Asia and the Americas.

Of course, the Renaissance in general and its culture of ‘eloquence’ (eloquentia) took a slightly different form beyond Europe. While European orators praised the kings, popes, senators and petty despots who ruled the continent’s patchwork of monarchies and republics, those in Latin America and colonial Asia applied the rules of classical rhetoric to praise their distant monarchs and to spread Christianity via sermons in local languages in ways that required them to carefully translate European ideas into a form that would be understood locally. In this ‘Empire of Eloquence’ (as I call it in my new book), Cicero and the tradition that he embodied interacted with local languages and cultures to create hybrid Renaissances.

For instance, the 17th-century Portuguese missionary Miguel de Almeida clothed classical references in eloquent Konkani (the language of Goa) in his ornate sermons to celebrate saints’ days. This included references to Julius Caesar, Alexander the Great and even Anthony and Cleopatra. Of course, Almeida had to adjust their names to fit the needs of Konkani grammar and explain who they were using a mixture of local and borrowed Portuguese terminology, waxing lyrical about Roma Xarantu Emperadoru Iulio Cesar, or ‘Caesar, the Emperor of the City of Rome’, and what Caesar’s life could teach them about the path to virtue in a panegyric sermon for the Nativity of Mary.

The long shadow of Cicero even found its way into Jesuit sermons in Chinese, such as the homily delivered for the feast day of St Ignatius (cofounder of the Jesuits) by an Italian Jesuit named Giulio Aleni, in which he declared:

In general, rites held in commemoration of a saint have three most important functions. First, we praise and thank the Lord of Heaven for having produced the saint as a compass (zhinan) for later generations. Second, we gratefully admire the good works and virtues displayed by the saint during his life. Thirdly, we imitate (fangxiao) his virtuous conduct and try to make it our own.

In other words, although transported into a Chinese context, this was a textbook example of epideictic oratory that moved from praise of one specific example of virtue to the exhortation of a general set of Christianised Greco-Roman virtues. Cicero would have approved.

While the Renaissance itself would fade away everywhere in the course of the 17th century, the traditions that had been globalised during the age of Titian and Michelangelo didn’t disappear. Even in the Enlightenment, classical rhetoric in a new 18th-century form continued to be an important part of elite education in Latin America and colonial Asia, just as it was for their contemporaries in North America, like the Founding Fathers of the United States of America who attended Harvard College on the eve of the American Revolution. This would definitely recede only in the second half of the 19th century.

Fascinatingly, one of classical rhetoric’s last hurrahs came in 1844, when Manuel Micheltorena, the Oaxacan governor of Mexican California, delivered an oration to celebrate Mexican Independence on the eve of the Mexican American War. Standing before the presidio church in Monterey, the orator celebrated the struggle for independencia o muerte in a highly rhetorical style with constant reference to the Roman Republic, and praised Mexico’s equivalent of George Washington, Agustín de Iturbide, in this way:

Almost all the parts of the Republic give irrefutable testimony of the valour and wisdom of that great general who in these virtues approached Caesar and Alexander, Pompey and the Prince of Condé. Those principles contained in the Constitution are certain proof of his lack of self-interest, and that without abusing his power he only used the free rein given to him by the nation in the Tacubaya agreement to do good and resist evil. Did not Regulus, Cicero and Trajan do the same in ancient Rome, and the great Washington in the modern United States?

So, next time you think of the Renaissance and its influence, by all means think of Florence, Milan and Rome. But also leave some space for Mexico, Goa and Japan. The glory that was Greece and Rome cast a long shadow indeed.