If you have ever loved unrequitedly, then you know that living without any hope for a future with your beloved is a bitter experience indeed. When in love, we usually have a deep desire that our beloved love us back. If they don’t, it can pain us very much. We might, in all likelihood, come to wish that we didn’t love them, that we could stop loving them, or even that we had never loved them at all. Even if you haven’t experienced this for yourself, then you can probably imagine the agony involved.

No wonder that people employ all kinds of techniques to get over those who don’t come to love them back. In George Eliot’s novel Daniel Deronda (1876), Rex Gascoigne, after being rebuffed by the dynamic Gwendolen Harleth, begs his father to allow him to defect from England to Canada. I too once toyed with the idea of fleeing to the Canadian Rockies in the wake of heartbreak in Toronto. Others might seek comfort in a weekend, or a few, of heavy drinking, or find themselves set up on a series of uncomfortable blind dates by overbearing sympathisers. Indeed, friends will offer us all sorts of concoctions and home remedies. Those who have loved unrequitedly, however, know: though this friendly advice is no doubt well meant, it is also misguided. For while the proposed remedies might give us time and opportunity to heal from the hurt of the disillusionment, they will not cause us to stop loving.

Why not? Because the fact that it would be better to stop loving is not itself sufficient to stop us loving. Prudential reasons to fall out of love simply miss the mark, given the nature and structure of love as arational. But the situation is not entirely wretched. I hope to persuade you that, while unrequited love is bitter, it can be made bittersweet, if you change your attitude toward it.

Rational love is love justified by reasons: for example, we might imagine Leo Tolstoy’s character Anna Karenina loving Count Vronsky for the reasons that he is charming, persistent and attentive. Arational love, by contrast, is love that is not justified by such rationales. There are many reasons why I believe romantic love has this arational form, one of which is a puzzle known to philosophers of love as the ‘problem of particularity’. It goes like this: if it’s true that love is rational, and that we love people for reasons such as their charm, persistence and attentiveness, it’s not clear why we should love any one particular charming person over any other. All sorts of people are charming, persistent and attentive. Why love Vronsky?

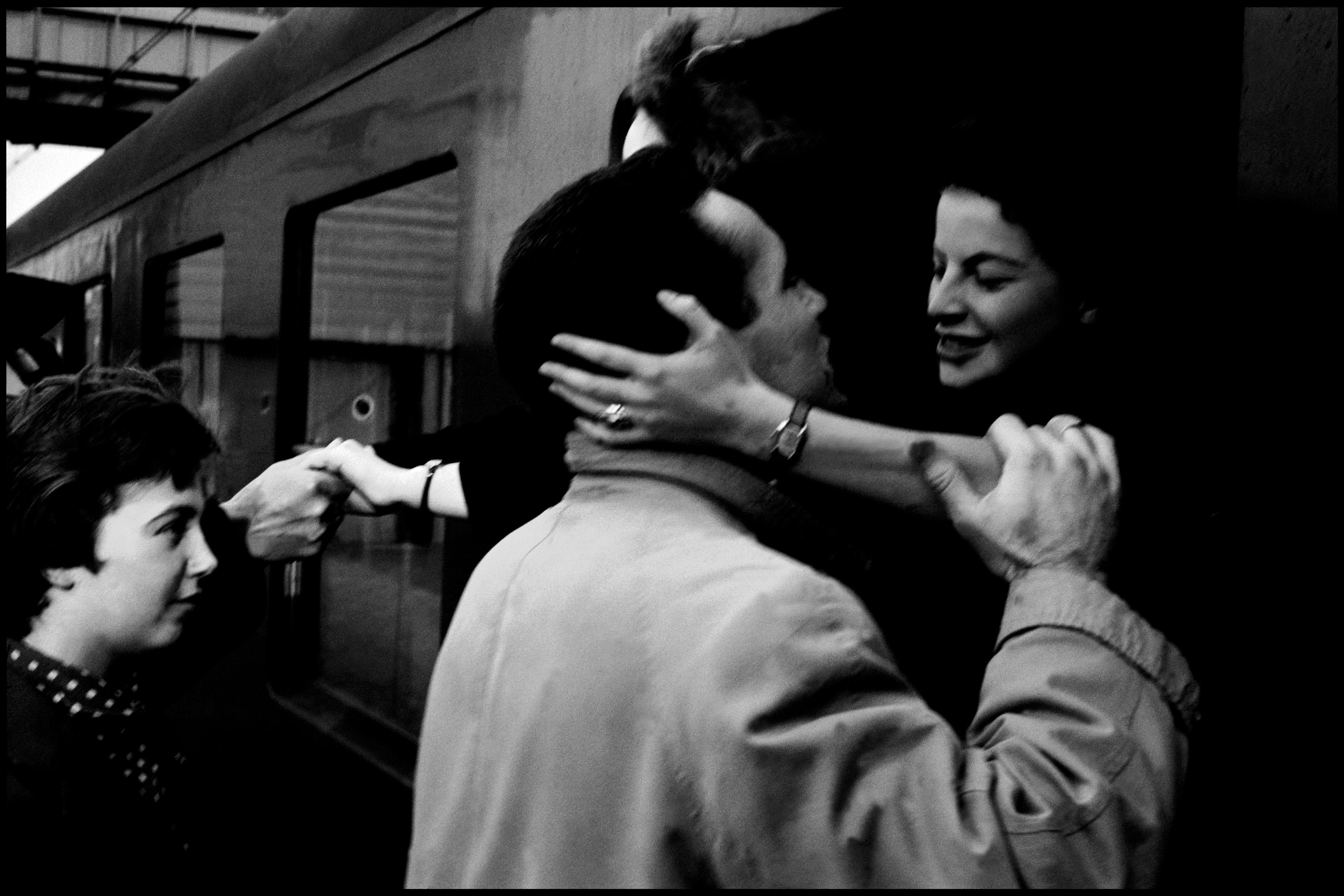

Some commentators, such as the philosopher Niko Kolodny, believe it is the shared history of a relationship that solves the problem of particularity and provides a rational reason for romantic love. After all, while there might be many charming people in the world, only Count Vronsky first met Anna at that Moscow train station. In the case of unrequited love, however, there is a strong reason to doubt that this is correct. After all, doesn’t unrequited love sometimes blossom upon first sight or develop over time for a near stranger? If love is possible in the absence of a relationship, the relationship cannot serve as its reason.

We might even think of romantic love as not only arational, but also unconditional

So I say that love is arational. In consequence, though it may indeed be ‘better’ in a pragmatic sense for the heartbroken lover to move on, this higher-order reason will not cause or persuade us to actually move on. Love is not the sort of thing justified or undone by reasons.

Some might say, but what if this love is causing harm? If loving pains the unrequited lover, surely this, if nothing else, gives them reason to stop loving. Yet, I repeat once more, love is not the kind of thing that is swayed by reasons, even this one. To borrow from William Shakespeare, once in love, we can love someone ‘even to the edge of doom’. Take Charles Dickens’s character Sydney Carton and his love for Lucie Manette in A Tale of Two Cities (1859): though she did not love him – but loved another – still, he died for her sake, taking the place at the guillotine of the man whom she did love. In this way, we might even think of romantic love as not only arational, but also unconditional.

If you are one of those who has loved unrequitedly and you are persuaded by my arguments that your love is arational and unconditional, and therefore immune to rational or deliberate undoing, you might at this point be in some renewed distress. But please fear not, for I believe there are compelling reasons to embrace your predicament. (Note, I am not referring here to abusive relationships in which one partner withholds love as a means of manipulation.) I have already said that unrequited love can be deeply painful, and I stand by this – but I hope you will forgive my saying that, if it is torture, it is torture of the most sublime and exquisite kind. And I believe that an exquisite torture is a torture worth bearing. The unrequited lover need not wish so impatiently for their love to end. Instead, they might embrace their love, for however long it persists. If you embrace your love, unrequited though it may be, it need not hurt you so.

What does it mean to embrace love? Well, though love itself is arational, it seems plausible that we can still take certain attitudes toward it, doing so for reasons. If we reject our love, this can cause in us a kind of rift – we do not endorse our love, and yet we can’t help but love. This results in a kind of alienation contributing to our ultimate experience of bitterness. If instead, however, you can adopt an attitude of affirmation, you need not be at odds with yourself. This is what I mean by ‘embracing’ unrequited love: adopt an attitude of affirmation toward it by telling yourself: ‘I’m in love, and that’s OK.’

You might worry that prudential reasons for embracing your unrequited love are the ‘wrong kinds’ of reasons; that the notion ‘It would be better for me to embrace my love’ does not give you the right kind of reason to actually do so. Understandably, you might think that having certain attitudes requires having certain beliefs. For instance, that having an attitude of affirmation toward your love is not possible if you don’t really believe that it is OK that you are in love. Fortunately, I can offer a powerful nonprudential reason for you to embrace your unrequited love: it is sublime.

That love is arational, and that we are capable of it, is something to rejoice in. Small, trembling creatures though we may be, we are capable of arational, unconditional love, which is the closest we may ever come to the infinite or the eternal. I am thinking of something akin to Immanuel Kant’s mathematical sublime, though I may be one of the only philosophers to accuse his third Critique (1790) of being romantic. To paraphrase Kant, the fact that we are capable, over and above reason, of feeling something so immense, so overwhelmingly powerful, so beyond our control ‘indicates a faculty … which surpasses every standard of sense’.

Love is not a choice, and yet it is still something you do, not something that merely happens to you

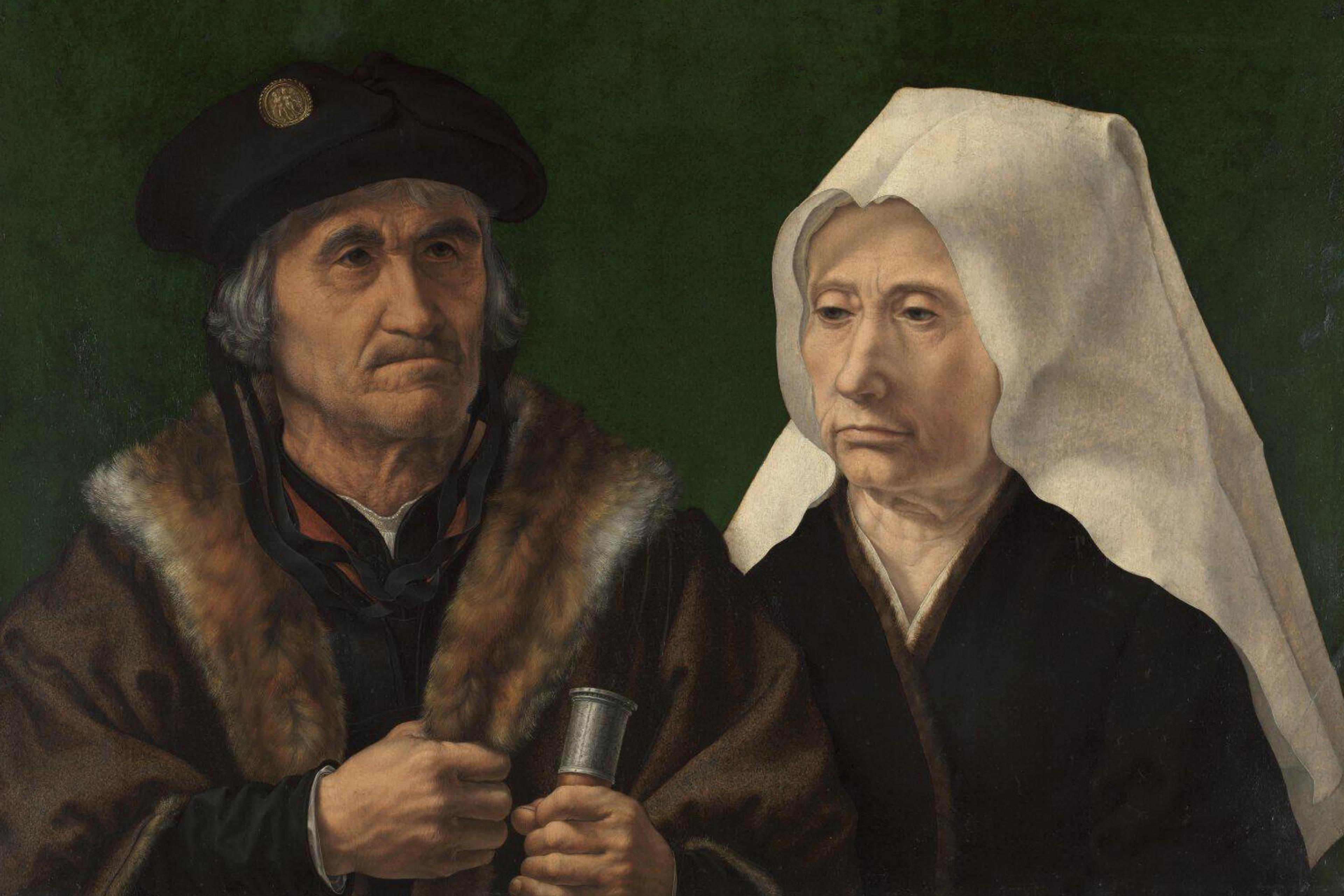

To love is to exhibit a capacity beyond the capacity of sense, and even beyond that of reason. The depth of feeling of which we are capable is the ultimate expression of our humanity, and our relative helplessness before it is perhaps the essence of what makes us human. As W H Auden wrote: ‘If equal affection cannot be, / Let the more loving one be me.’ If love is mathematically sublime, however, then it is only metaphorically so; surely love needn’t be strictly either mathematical or dynamic in order to be sublime. After all, the sublime is, for Kant, the closest that one may ever get to peering over the edge, to looking beyond the phenomenal (thinkable) world.

Love is, therefore, perhaps best thought of as sublime because it either is, or at least gestures at, something that we cannot quite make sense of. Indeed, see how we look for the reasons of love – we want love to be rational so that it may be sensible! Yet love defies your sense-making strategies: love is not a choice, and yet it is still something you do, not something that merely happens to you. There is something incomprehensible about this, and this reflects a deep incomprehensibility and essential mystery about the nature of agency, even of our own agency over ourselves. Our experience of and attempts to analyse love are perhaps the closest we can come to having an account of the self that is outside of the limits of practical reason. Love is something that exists on the maximal outer limit of our agency’s thinkability. Love is therefore sublime in that it gives us a glimpse of the supersensible.

In short, love – including unrequited love – is exceptional. It can endure anger, pain and grief, persisting against all odds, existing in the unlikeliest of places and times. Though it may pain you that your beloved does not love you back, take comfort – in loving, you are peering over Kant’s edge. The edge is not something to be shied away from, though it is formidable. Rather, regard the precipice with awe and rejoice in your proximity. Though this claim may not be ultimately satisfactory to some, I mean it to be more than a salve. Romantic or otherwise, returned or not, love is sublime and worthy of embrace because it reveals in you, the lover, a unique and noble capacity.