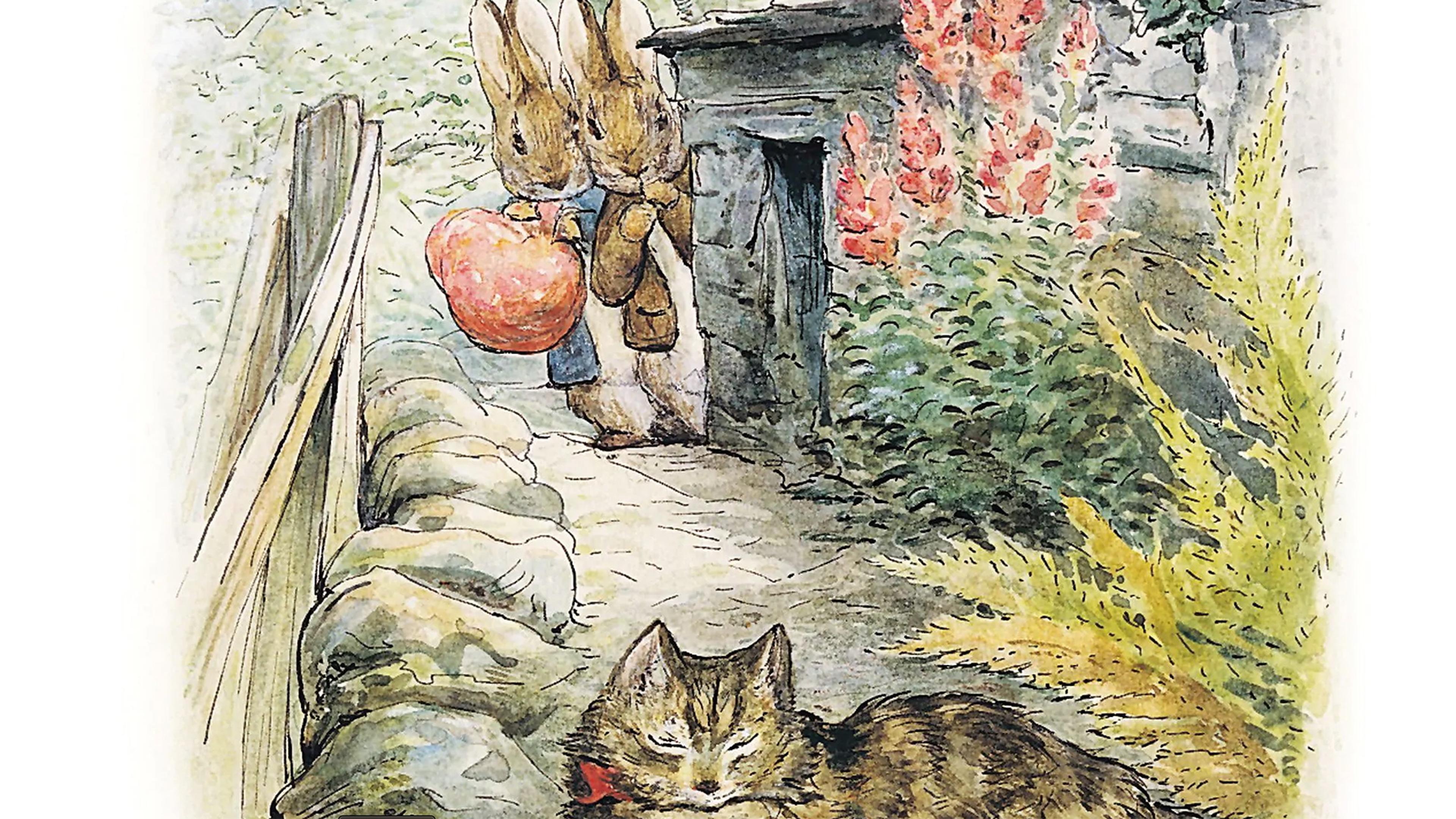

Once upon a time, there were four little rabbits, and their names were Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail and Peter. They lived with their mother in a sandbank underneath the root of a very big fir tree. One day, their mother dropped them off at soccer practice and picked them up promptly afterward. When they got home, they all had bread and milk and blackberries.

That is roughly how the classic Beatrix Potter story from 1902 would go if it had been set in the American suburbs. But even if Potter hadn’t set her books in England’s Lake District, she would never have chosen a suburban setting. The suburbs kill the narrative adventure that is the lifeblood of children’s literature.

Reading picture books to my children over the past 10 years, I’ve noticed how many of the stories shun a suburban setting. This is no accident: the tales that most grip the imagination of children (and adults), with few exceptions, require rural or urban locations for their drama and vitality.

To simplify, the antithesis of North American suburbia is walkability, and picture books with literary merit love walkability. Compelling children’s stories require that their characters are able to navigate their setting at a pedestrian scale and pace. For example, in the US author Arnold Lobel’s classic stories of the 1970s, Frog and Toad never appear in a car, despite being thoroughly anthropomorphised. What most draws the reader into the stories are the adventures that the amphibians experience between their houses – in the meadow, the woods and the tall grass. They climb mountains and swim in ponds, but they also walk everywhere: to fly a kite, to buy ice-cream, to fulfil a to-do list.

From Adventures of Frog and Toad by Arnold Lobel. Image © the Estate of Arnold Lobel/Amazon

The plots of the Frances stories of the 1960s and ’70s written by Russell Hoban and illustrated by Lillian Hoban also revolve around walkability. Frances can walk to the general store and buy a tea set or a Chompo bar. Her trips on foot to her friends’ houses frequently initiate narrative adventure. ‘Today is my wandering day,’ announces Frances’s friend Albert, on which he likes to catch snakes, walk on fences and look for crow feathers. ‘Wandering days’ in American suburbs, however, are infrequent or nearly impossible. Walkable environments preserve independence for the young, who are often the main characters in children’s stories.

Consider George and Martha as yet another example. The only cars we see them in are the bumper cars at the amusement park. The US writer and illustrator James Marshall’s beloved hippopotamuses of the 1970s and ’80s consistently engage meaningful, walkable destinations rather than sprawling subdivisions. They can hopscotch home after a visit to the store, comfort each other on their walk home from a scary movie, or push a bed to a picnic using roller skates.

In urban settings, walkability is closely linked to public transport, which is another narrative avenue for rich engagement with one’s environment. Accordingly, the number of picture books that feature trains and buses is significantly greater than the number of trains and buses that most Americans experience. Yet I’ve never seen a picture book that features a minivan or an SUV.

The zookeeper in Peggy Rathmann’s Good Night, Gorilla (1994) lives within walking distance of the zoo. In Erin and Philip Stead’s A Sick Day for Amos McGee (2011), the zookeeper takes the bus to work. Both commutes are integral to the stories’ plots, enabling shenanigans for the zoo animals.

Besides public transport, urban settings give other ample opportunities for their characters to explore their immediate environment. Cities are where we’re more likely to find civic places, such as zoos, libraries or concert venues. Cities tend to have more diverse kinds of people and more intergenerational activity in both public and private places than in suburbia. Good picture books such as Ben’s Trumpet (1979) by Rachel Isadora and A Chair for My Mother (1982) by Vera Williams exploit these opportunities in their stories.

It’s one thing to find enviable walkability in Esphyr Slobodkina’s Caps for Sale (1940) or Margaret and H A Rey’s Curious George series (1941-66) or Ludwig Bemelmans’s Madeline series (1939-61) – books written by European émigrés to the US well before American housing developments and ‘big box’ stores became the dominant pattern of land use in the mid-20th century. But to continue to find dynamic city living in bestsellers such as Bernard Waber’s The House on East 88th Street (1962) or Mo Willems’s Knuffle Bunny (2004) is revealing. (That both stories feature beautiful Victorian brownstones as their backdrop is a bonus.) Celebrated American children’s books authors such as William Steig, the creator of Shrek, and Tomie dePaola consistently chose pre-modern settings for their stories, so the suburbs hardly even had a fighting chance.

From Knuffle Bunny (2004) by Mo Willems. Courtesy Walker Books

More than any other works of fiction, picture books depend on their setting. When the automobile dominates the setting, the narrative dies faster than a trip down a cul-de-sac. Even when there are private modes of transportation in children’s literature, they are ships, bicycles or hot-air balloons, where the transported are engaged with the world around them and the adventure or mystery that this world brings.

Of course, children’s books are not marked exclusively by the narrative. The illustrations arguably play an even more important role. And there are multiple reasons, aside from the fact that the stories lack suburban settings, to avoid illustrations of the suburbs. One is that contemporary suburbs are often ugly. Another is that sprawl is hard to fit into a page. So, naturally, we don’t find good children’s books that feature pictures of ‘snout houses’ (with a garage that protrudes in front of the house, and typical of suburbs in the US and Canada), strip malls or parking lots. Instead, we find beautiful illustrations of the countryside and forest, such as in Jane Yolen’s Owl Moon (1987) about a girl and her father who set out in the snow to look for an owl, or of the vibrant cityscape, as in Mordicai Gerstein’s The Man Who Walked Between the Towers (2003) about Phillippe Petit’s high-wire stunt in Manhattan, or the Paris of the Madeline stories.

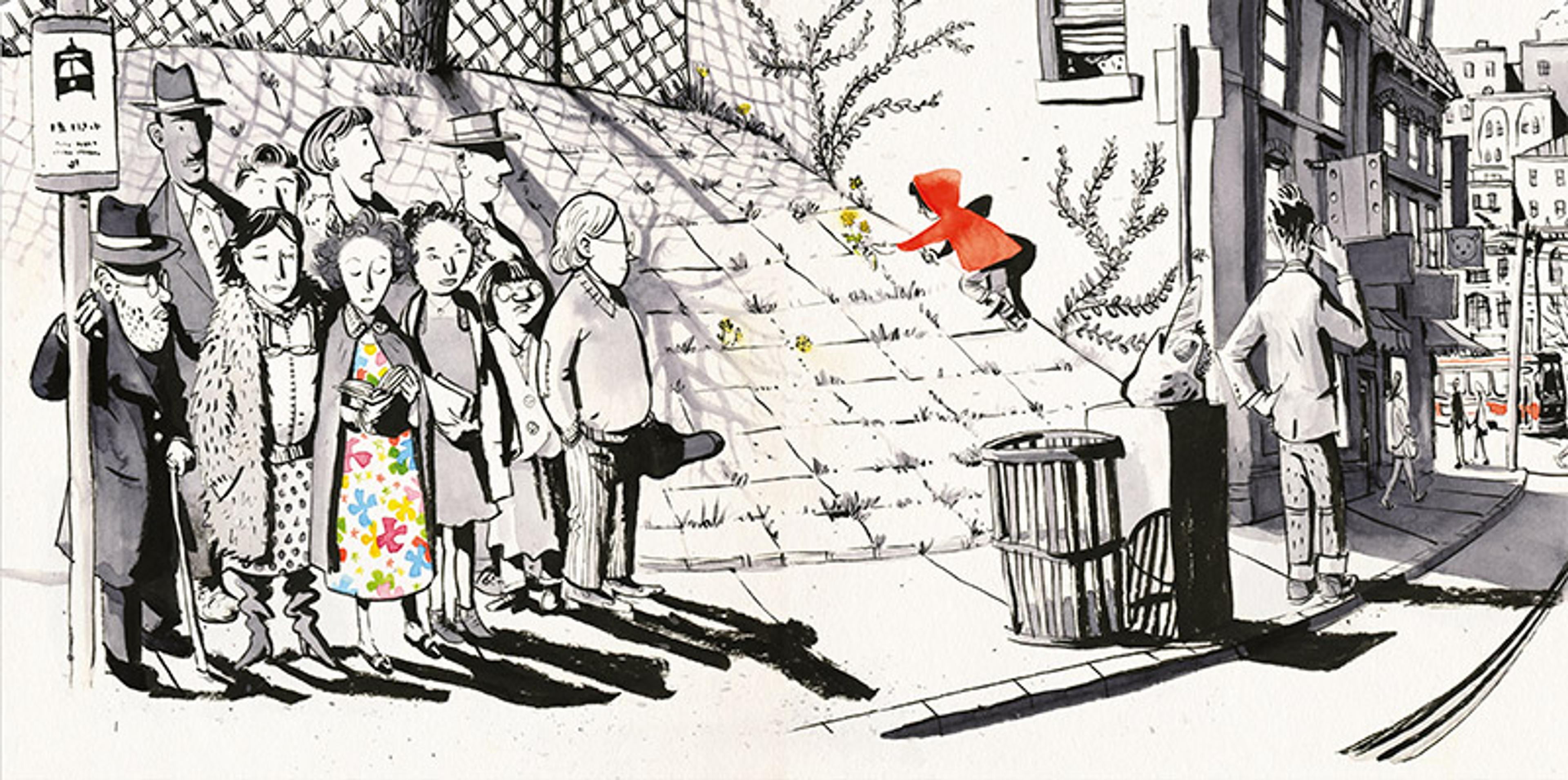

Sometimes, the pictures display such stunningly beautiful and rich environments – such as in The Mysteries of Harris Burdick (1984) by Chris Van Allsburg, or Sidewalk Flowers (2015) by JonArno Lawson and Sydney Smith – that they carry the story with few or no words at all.

From Sidewalk Flowers (2015) by JonArno Lawson and Sydney Smith. Courtesy Walker Books

In a number of cases, the setting for a children’s picture book isn’t relevant to the argument I’m making here because the setting has nothing do with the built environment or the natural environment. In some picture books (for example, Drew Daywalt’s The Day the Crayons Quit (2013), illustrated by Oliver Jeffers) there’s really no setting to speak of. In other cases, the setting is entirely indoors or entirely fantastical. It’s not enough that a story takes place exclusively within a single-family home for it to count as suburban. Margaret Wise Brown and Clement Hurd’s Goodnight Moon (1947) could well be suburban, but it also could be rural. What we don’t find in Goodnight Moon is the old lady driving her Chevy Suburban out of her subdivision of single-family homes to a Wal-Mart for some sleeping pills.

It’s true that some popular picture books do seem to have a suburban setting: Victoria Kann’s Pinkalicious series (2006-), the Berenstain Bears series (1962-) by the Berenstain family, and Norman Bridwell’s Clifford the Big Red Dog (1963-) come to mind. But these books also come to mind when I consider books I’d rather burn than read – not because they take place in the suburbs but because they’re so poorly written and illustrated. My only claim here is that the best children’s books forgo suburbia.

There are, nevertheless, some exceptions to this rule. In Judith Viorst and Ray Cruz’s classic 1972 picture book, for example, Alexander appears to be chauffeured around the suburbs by his mother; in that scenario, who wouldn’t be having a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day? But for every quality picture book that has a suburban setting, there are 100 that don’t.

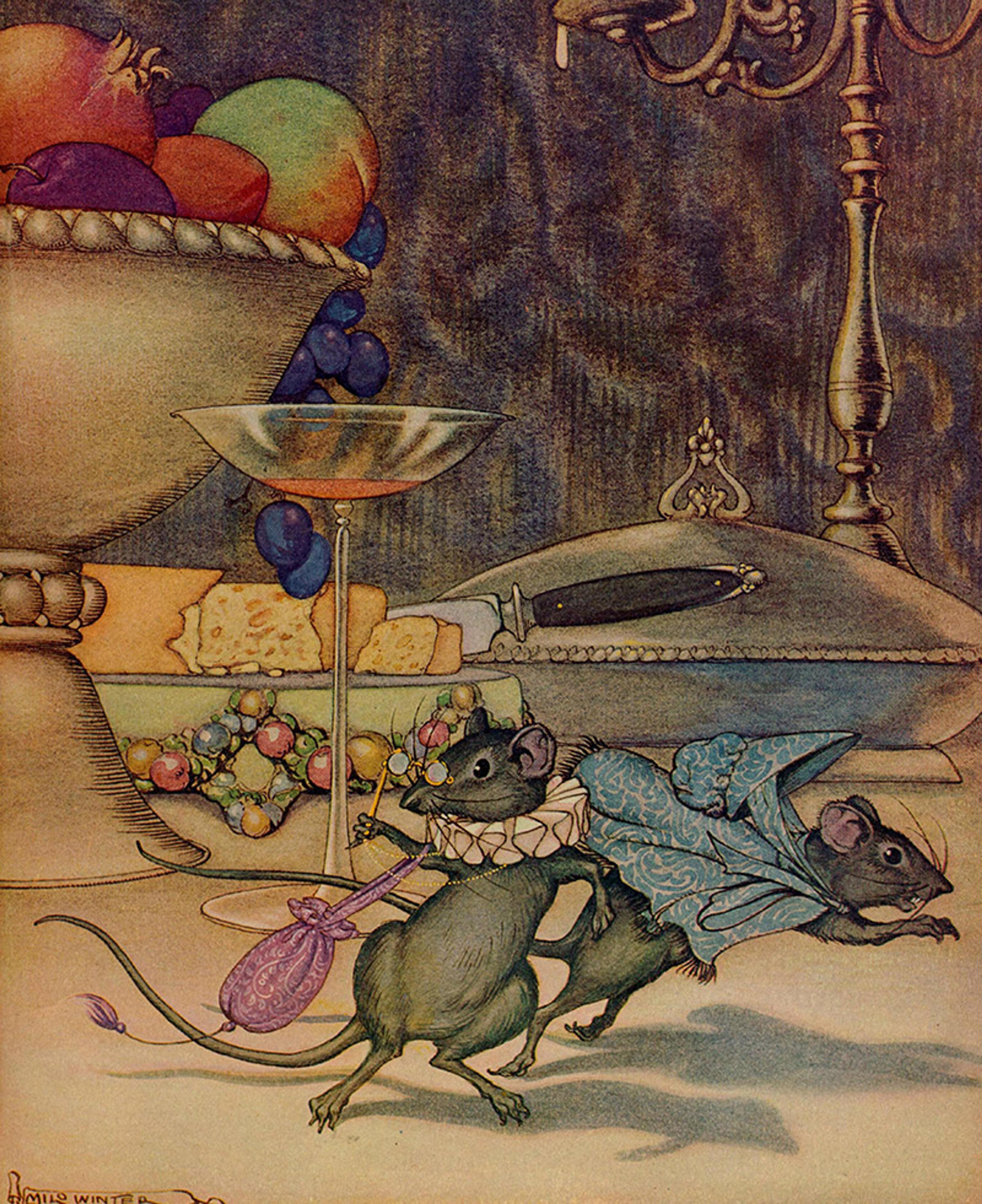

Illustration for Aesop’s fable The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse. Photo by Alamy

At least since Aesop’s fable The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse, many children’s stories exhibit a kind of anti-urban romanticism, of which Virginia Lee Burton’s The Little House (1942) is one memorable example. Cities are dangerous and dirty places in contrast to the idyllic countryside. Books set in cities often react against this trend by showing the benefits of city life. Yet this counter-reaction is, arguably, guilty of romanticising the urban. Children’s books that use pedestrian settings, whether urban or rural, fall prey to both kinds of romanticisation, displaying exclusively the attractiveness of a walkable town or a tranquil forest. However, the accuracy of these portrayals is not the point of the settings. Rather, their job is to serve the narrative and delight the reader.

Children’s literature thrives on imaginative or surprising encounters, which need a geography that creates mischief and curiosity. But the suburbs, for all their benefits in real life, are places that in children’s literature lack imagination, or at least don’t provide suitable stage-sets for imaginative adventure and exploration: they are the geography of nowhere. Consequently, the most engaging stories are almost never set there.

In Matt de la Peña and Christian Robinson’s Last Stop on Market Street (2015), a young boy and his grandmother ride a bus from church to a soup kitchen. ‘What do we need a car for?’ asks Nana. On the bus they encounter a blind man with a spotted dog and an old woman with curlers who has butterflies in a jar. A man begins to play a guitar right on the bus. The boy closes his eyes and his imagination transports him into a place of waves and hawks and sunset colours, as ‘the sound gave him the feeling of magic’. The author shifts the setting quickly from urban to rural, bypassing the suburbs entirely and reminding us that valuable picture books enchant readers, young and old, by their sense of intrigue, wonder and beauty.