Have you ever wondered whether or not you are normal? Think about the last time you asked yourself that question. What did you mean? Maybe you were considering if an attribute was healthy or not. Perhaps you were concerned that the way you look or behave didn’t quite meet a perceived ideal. Or maybe you simply wondered whether you fitted in: do you think and act and live ‘like everyone else’?

Few of us are immune from the mysterious power of the so-called normal. I spent my socially awkward teens and 20s obsessed with this mysterious state. I was positive that my life would be better and happier if I could only be a bit more like other people. But then, one day, I asked myself a different question. Who are all these so-called normal people out there? Do they even exist?

Before the early 19th century, the word ‘normal’ was not applied to human beings at all. It was a mathematical term, meaning a right angle. People compared themselves with each other, of course, but largely on an individual level: the normal as a generic state of being or behaving simply did not exist. Our modern notions of normal emerged in Belgium in 1835, when Adolphe Quetelet, a 39-year-old astronomer and statistician, began the trend of comparing human characteristics against an average. Quetelet discovered that if you plot a large set of data on a graph – the individual heights of thousands of people, for example – it often makes a bell-shaped curve. The heights of the largest number of people will fall around the peak at the centre, with a rapidly decreasing tail on either side where fewer people are much shorter or taller than the average.

This spread of heights is simply what happens to exist. There is nothing intrinsically desirable about being a particular height. But the ‘normal distribution’ (as it became known) was also the astronomer’s error curve, popularised by the mathematicians Carl Friedrich Gauss and Pierre-Simon Laplace soon after 1800. Astronomers’ measurements were invariably subject to error. They knew that small mistakes were made more frequently than large ones. By taking multiple measurements of the same thing, they could better determine the correct distance or trajectory of a planet or a star. For the astronomer, the centre of the bell curve was not only the average – the mean, median and mode all align in a symmetrical normal distribution – but also the correct measurement.

Quetelet assumed that the same thing applied to people: those who happened to be closer to the average were also nearer to a correct or ideal way of being. As he wrote in the preface to the 1842 English translation of A Treatise on Man, the book outlining his method of ‘social physics’: ‘[E]very quality, taken within suitable limits, is essentially good; it is only in its extreme deviations from the mean that it becomes bad.’ The ‘average man’, as Quetelet called him, was also the ideal human being, in body, mind and behaviour. This can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. If everything is designed for someone of average height, from the length of a bed to the height of a table, then this average man inevitably becomes the ideal human within that society.

This notion that average and ideal might be one and the same thing, and that both are part of the definition of ‘normal’, infiltrated science and medicine for well over a century (and lingers in our popular understanding of what’s normal even today). For instance, in 1967, when the young psychiatrist Paul Horton investigated the meaning of ‘normal’ in psychiatry, he found that most of his fellow doctors ‘consciously defined their notions of normality as being a hybrid of the normality-as-average and normality-as-ideal perspectives’ – not that they could agree on what normal, everyday behaviour looked like. For example, when Horton asked his peers how a hypothetical ‘typical normal person’ would behave if called a ‘stupid idiot’ by his boss in front of colleagues, their answers ranged from ‘annoyed but decides to forget the whole thing’ to ‘much anger – quits his job’.

Notions about what counts as normal behaviour vary even more dramatically across time and place. In 1898, when Edith Cotton – an inpatient at Bethlem Hospital in London – refused to wear a hat out of doors, this was deemed a sign of mental illness, because wearing a hat was right and proper. Meanwhile, so-called ‘new women’ scandalised late-Victorian England by cutting their hair short and sitting upstairs on the omnibus, acts that appear quite uncontroversial in most Western countries today. Even our everyday, unconscious mannerisms can seem normal or abnormal depending on where we are. I didn’t notice how often I smile at strangers – a brief acknowledgment when passing in a doorway, or buying something in a shop – until I visited Poland 10 years ago and was met with a confused stare when I did so. According to my guidebook, smiling at strangers was seen as a sign of stupidity; others did not smile back.

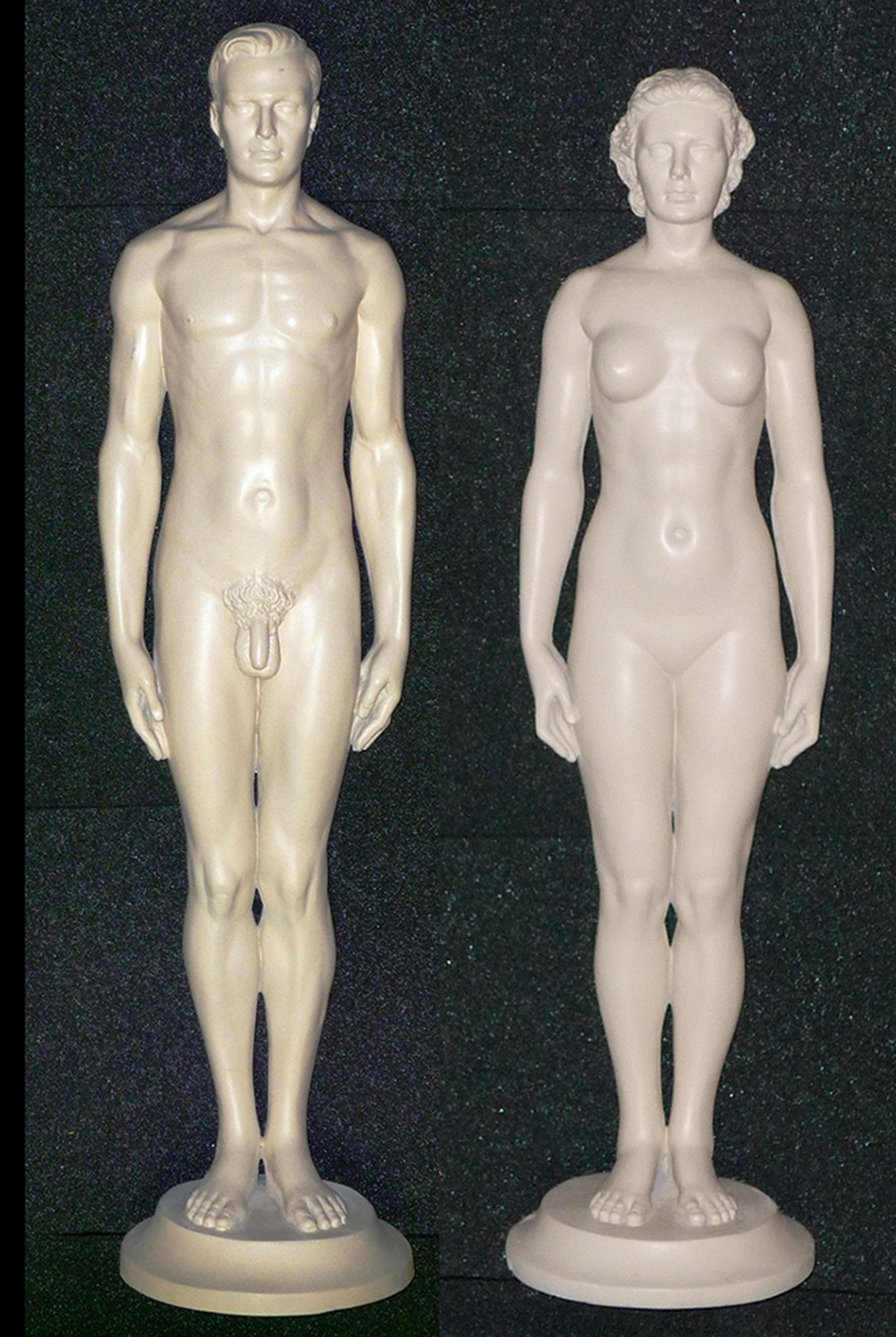

Quetelet’s term ‘average man’ (l’homme moyen) also points to another challenge in the definition of the normal human. We might assume that normal is a kind of universal standard, but expectations are usually drawn from a much smaller subset of people. The data used to create any mathematical average tends to be selected in accordance with the prior assumptions of a scientist as to what is normal; a skewed result then reinforces the notion that their preferred group is particularly representative. For Quetelet, to be normal was to be male. For Francis Galton, the Victorian scientist who introduced the term ‘normal distribution’ alongside his racist science of eugenics, normal also meant middle or upper class. And in the case of the average American figures created by the sexologist Robert L Dickinson and the sculptor Abram Belskie, and donated to the Cleveland Health Museum in 1945, to be normal was to be white and youthful.

Dickinson-Belskie models of ‘Normman’ and ‘Norma’ (1939-1950), half-size. Courtesy the Warren Anatomical Museum, Countway Library, Harvard

Dickinson and Belskie used the physical measurements of tens of thousands of American men and women to create two sculptures that they named Normman and Norma. The statistics they used came only from white Americans, and young adults predominated. In Norma’s case, much of this data was taken from an interwar study to develop standardised clothing sizes. This study’s researchers noted that, ‘for the sake of good feeling within a group’, they had measured ‘a few women of other than the Caucasian race’ who volunteered, but then promptly and inexplicably discarded their data. Norma and Normman were held to be a universal average, but were created by a biased sample.

The final irony, though, was that these normal Americans didn’t even exist. In 1945, a local newspaper held a competition to find the real-life Norma. They printed a standardised entry form for readers to send in just nine vital statistics: height, bust, waist, hips, thigh, calf, ankle, foot and weight. From 3,864 entries, the newspaper chose a winner: Martha Skidmore, a 23-year-old white woman who worked as a theatre cashier. However, even Skidmore did not meet Norma’s measurements exactly; she was simply the woman who came closest. A mere 1 per cent of women entering the competition came anywhere near Norma’s measurements. While some of us might be average in one or even two characteristics, the chances of hitting the mathematical mean on nine different measurements is so statistically small as to be well-nigh impossible.

But because the application of the term ‘normal’ to humans has always conflated average with what is desired, Norma created an expectation that went beyond a particular size or shape of body. When the bright white plaster statues of Norma and Normman were displayed to the public as ‘Native White American’ (according to their label in the Cleveland Health Museum), this set a standard. The ‘normal’ American was white, youthful and athletic; those already marginalised by their exclusion from the study’s data (people of colour, disabled and/or older people) were now also deemed to be less American. Similarly, the 1917 Army Alpha IQ test judged participants on their knowledge of middle-class American culture, and concluded that those who were less familiar with it (immigrants and working-class people, including many people of colour) were less intelligent. As with the average man, this reinforced the idea that a certain type of person was ‘normal’ even if they were not the most statistically numerous.

It’s almost as if we haven’t learnt from the way that, time and again, our assumptions about what’s rare or out of the ordinary are proven to be just that: assumptions. In 1889, a Census of Hallucinations carried out by the Society for Psychical Research showed that seeing or hearing things that others did not was more common than expected and did not necessarily indicate ill-health. In their survey of 17,000 people, 2,272 (13 per cent) said they had experienced hallucinations, a figure reduced to 1,684 (c10 per cent) when some experiences, including delirium from fever and dream states, were discounted by researchers. And in 1948, the sexologist Alfred Kinsey found that, contrary to popular belief, same-sex acts were common and ‘a significant part of human sexual activity’. Meanwhile, the social model of disability, developed in the 1970s, contended that disabled people are not disabled by their physical attributes or health conditions but by a society that fails to adapt to their needs: a society designed for the so-called average man. Normality is as political as it is medical.

And yet many people still question their own normality, day in and day out. At times, this can be a useful exercise. It may enable us to spot life-threatening disease or support ourselves and our loved ones through difficult experiences. When my partner suffered from recurrent urinary infections, for example, I remember insisting that this wasn’t normal for men, and that he should go to the doctor; he turned out to have prostate cancer. The fact that the idea of normal sometimes has a use, though, shouldn’t stop us asking ourselves exactly what norms we are using as a comparison. Are we unwittingly making assumptions about class, race, gender or sexuality? If so, it’s probably because that’s what centuries of scientists have told us to do, and these notions have become so embedded in our lives that often we don’t even notice they exist.

This is the case even though difference and not sameness is the rule in humankind. The Grant Study of normal young men, which began in 1938 at Harvard Medical School, investigated a tiny, elite subset of the US population. Even so, there was huge variation among them. Their resting pulse varied from 45 to 105, and respiratory rate from 4 to 21 breaths per minute. Even body temperatures differed, ranging from 97°F (36°C) to 100°F (37.8°C), with ‘not more than 18 per cent of individuals’ having the ‘usually accepted average’ of 98.6°F (37°C). Behaviour and personality varied even more. The concept of normal was often reinforced by the fact that, as Kinsey wrote in Sexual Behaviour in the Human Female (1953), scientists have ‘to deal with averages in order to compare the most characteristic aspects of two different groups.’ These averages, Kinsey went on to point out, mask individual variation that actually, he concluded, was ‘the most persistent reality in human sexual behaviour’. He found that people varied as a group much more than, say, men and women differed as sexes.

If I could travel back in time to reassure my younger self, variation is the message I would take with me. ‘Why are you worrying about comparing yourself against an average?’ I would say. No one is average in everything, and average is not necessarily the same as healthy anyway. If you want to set yourself a goal or standard to achieve, think critically about what it is you’re trying to reach. The normal standards that have shaped our history have generally – albeit often unwittingly – been elitist and exclusionary, reinforcing prejudices about gender, race, disability and social class. In the end, what is most common or usual across humankind is diversity and difference.