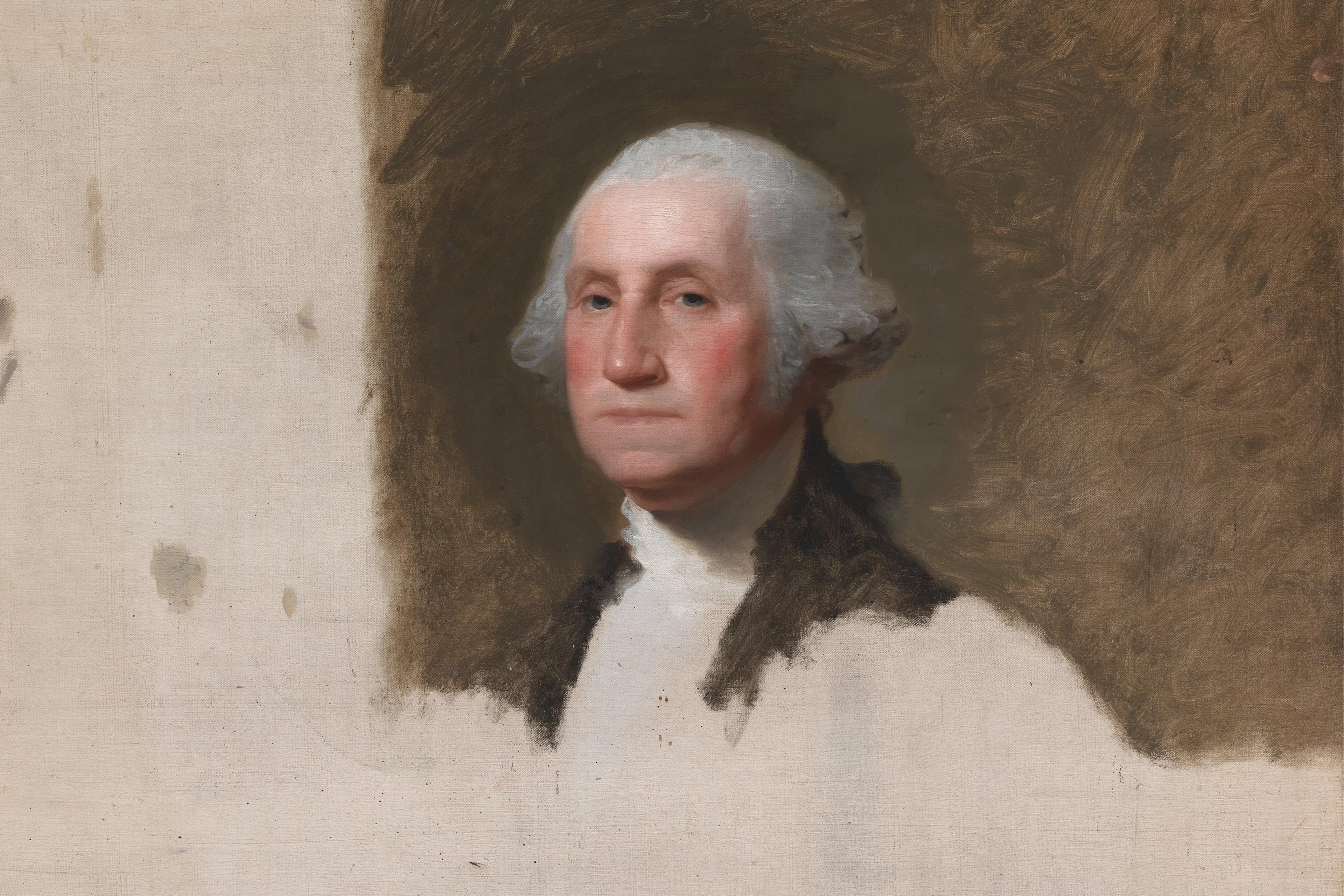

Whenever I take on a complex task – in my case, usually writing – I struggle to work fast and with abandon. Perhaps it’s because I’m an editor: every sentence must be crafted and justified. When this happens, one particular painting comes to mind. It reminds me how not to get things done, because it seems the artist spent too much time perfecting, not enough time completing. At least, so it appears.

The painting is an unfinished portrait of George Washington, the first president of the United States, by Gilbert Stuart in 1796. Known as the Athenaeum portrait, it was used as the basis for Washington’s face on the $1 bill. Not knowing its history, I have long liked to imagine that Stuart was similarly afflicted. I picture him starting with a perfect likeness of Washington’s head, but, in his tinkering, never getting around to the body.

With this image in mind, I try to pivot my approach closer to how a child might paint: messy splodges, working the pigment into shapes and forms, unconcerned with perfection. Finish first, edit later.

It turns out the truth behind the Athenaeum portrait is not what I assumed. Commissioned by the first lady Martha Washington, Stuart didn’t deliver the painting because he wanted to keep it. Before cameras, the partial image let him have Washington’s likeness in his studio to copy and sell. He supposedly called those duplicates his ‘hundred-dollar bills’.

Maybe Stuart wasn’t a perfectionist after all – rather, a pragmatist who knew when something was ‘good enough’ to serve its purpose. Perhaps that’s the real art of finishing: knowing when to stop, even if the work feels incomplete.

Sadly, I can’t print money from my own incomplete work. And if I want to publish this piece, I will need an ending; something that speaks of how to get a job done. [Insert satisfying final sentence here.]