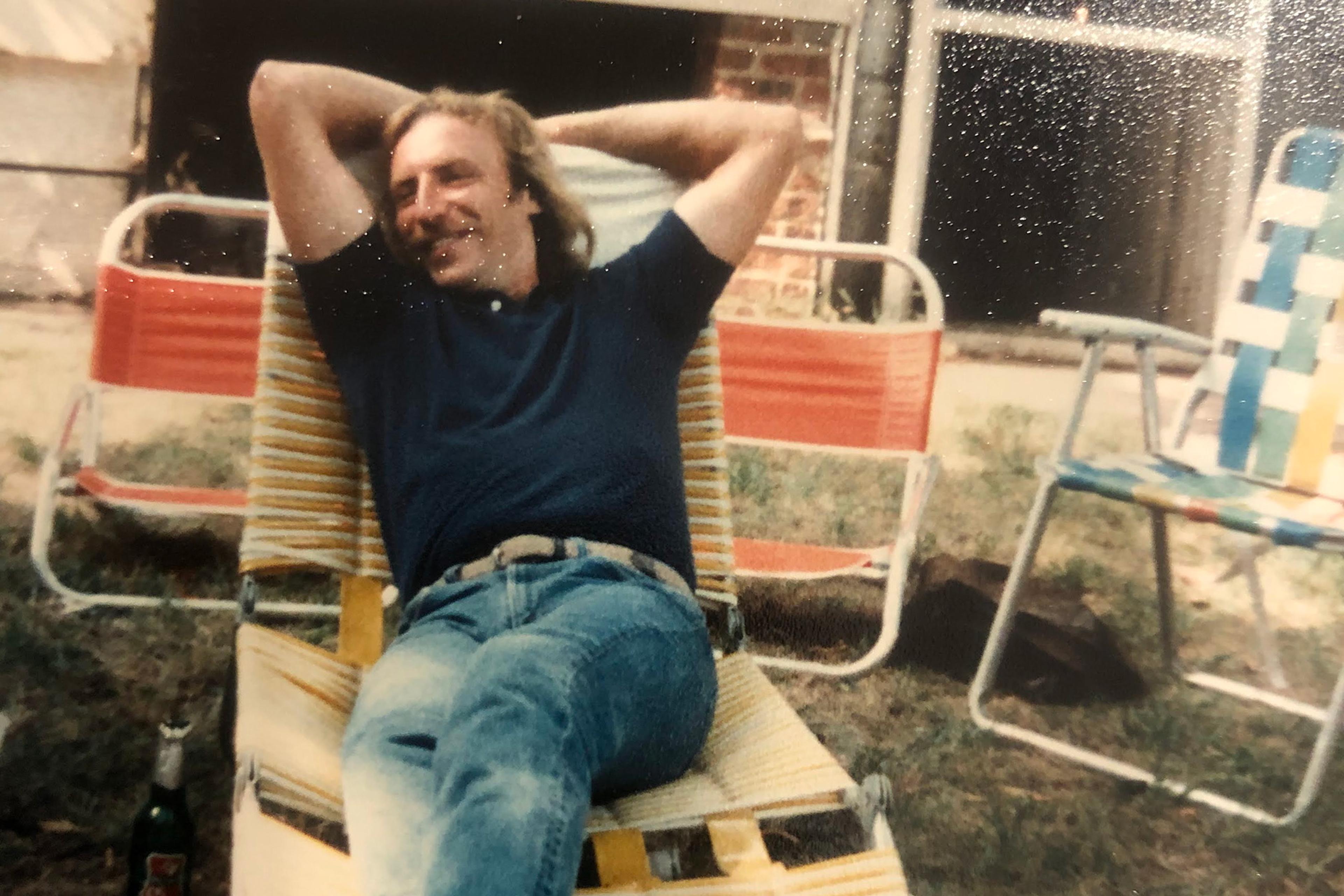

My son was two and we had just been discharged from hospital following a nasty winter bug. His birthday was only a few days away with no time to plan for a big party, so I invited a close family friend and her kids to a teddy bear-making workshop followed by a pizza. She agreed, huge relief – the problem was solved. But then she cancelled last-minute because apparently her children had received a better offer from a popular classmate who hosted great parties! My friend realised quickly that her honesty had fallen flat with me and so she came over to apologise.

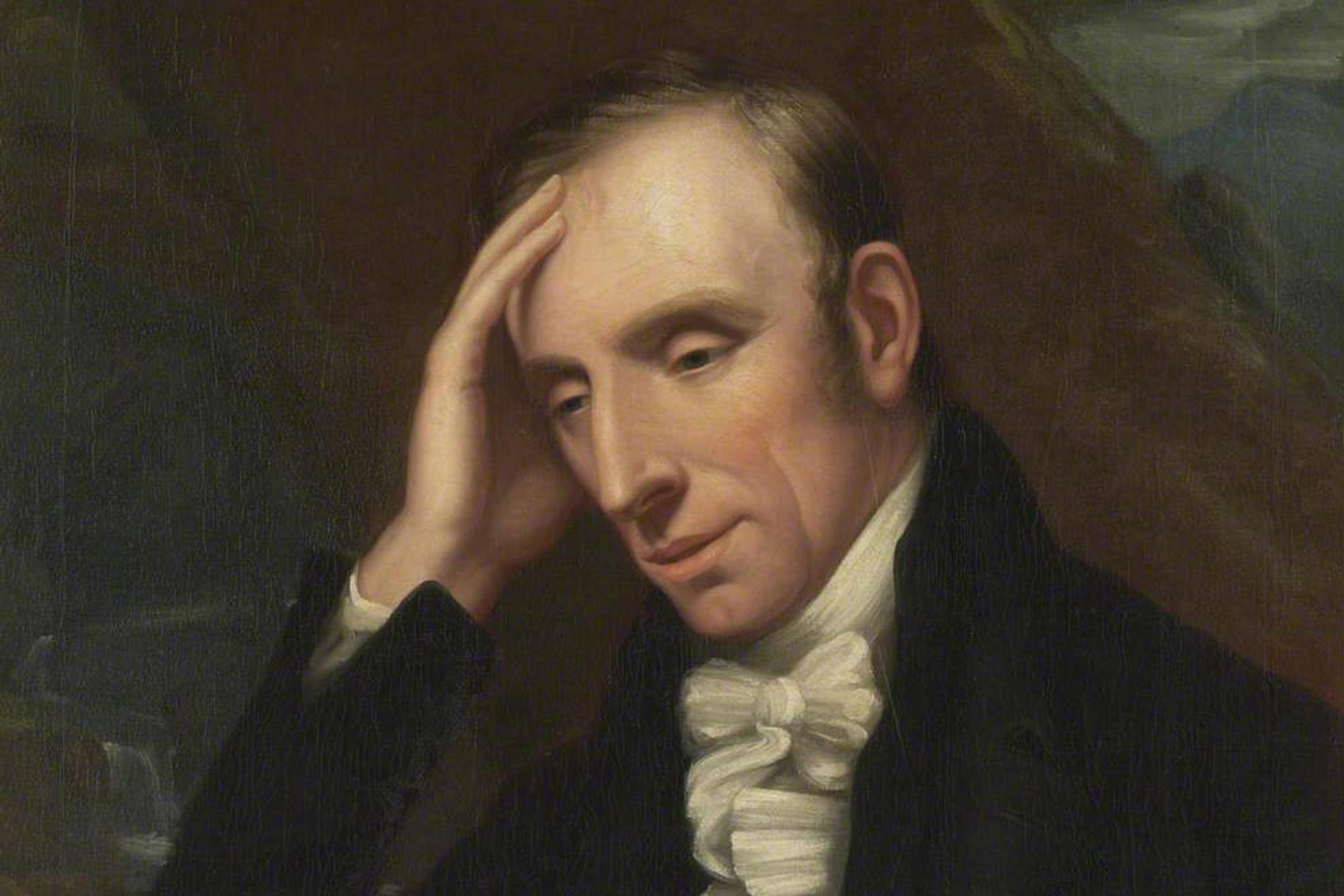

I was reminded of this event recently when I attended a lecture about the psychology of apologies by my colleague Shiri Lev-Ari. She described how research has shown that apologies are most convincing when they involve greater cost, such as in terms of money or time. My friend seemed to know this intuitively – she turned up on my doorstep (time cost) with a bottle of champagne (financial cost) at a time that would have likely inconvenienced her (effort cost).

Shiri wondered if this cost rule would extend to the words that we use when we apologise, and in her recent research that’s exactly what she found. People judged apologies involving longer words of explanation (I did not mean to respond in a confrontational manner) as more convincing than apologies involving shorter words (I did not mean to answer in a hostile way), presumably because they signal greater cognitive cost.

So, here’s my message to my friend: next time you need to apologise, do turn up with that that bottle of champagne but consider replacing your ‘real sorrow’ with ‘genuine remorse’.