I was arrested for the first time seven years ago, after I saw a policeman pushing an old lady to the ground. Her blood spattered on the street; chaos ensued. Tear gas filled the air. The medics who rushed to help her were also arrested. ‘What you’re doing is illegal,’ I told one of the officers, filming the whole time. There were many of them, outfitted in riot gear, outnumbering the mostly elderly protestors. Next thing I knew, I was in a police van, then in a small cell with no toilet, only a stone bench, and lights that never went out.

I’d been going to protests and pickets since I was a teenager, but didn’t initially relate to the demonstrators, who were part of the ‘yellow vest’ movement against inequality in France. One of their demands was against the imposition of carbon taxes; I was more ecologically minded. But I had friends going to demonstrations every Saturday who’d persuaded me to go too.

At the station, with my phone confiscated, I had no idea what time it was or how long I’d been there. I was still wearing the clothes I’d had on when I’d been blasted with tear gas; the itching and burning on my skin kept getting worse. Disoriented and unable to sleep, I began chatting with the people who’d been arrested alongside me. We talked for hours and soon they came to trust me, telling me various conspiracy theories: for instance, that the French president Emmanuel Macron was hiding cyanide in tear-gas canisters.

I found this ridiculous. ‘That doesn’t sound like an efficient or reliable way to kill protestors,’ I kept saying. But they were so convinced I made a note to look into it. Because of my PhD in molecular biology, my curiosity was piqued.

I was released after 24 hours. When I started reading up on tear gas, I was taken aback. Of course, the French government wasn’t trying to kill everyone. But there was something to what the protestors were saying: the tear-gas molecule is metabolised into cyanide. So I bought a detection kit and tested my blood, and the liquid in the special cartridge changed colour, indicating cyanide. I then reached out on Facebook to one of the men who’d been in that cell with me, and he put me in touch with other protestors. I encouraged them to begin testing their blood after demonstrations. We soon had 50 positive results with pretty high levels of cyanide.

To my astonishment, there were no recent studies on the impact of tear gas on humans; the few since the 1970s were based on animal models. Moreover, the amount of exposure scientists tested for back then was far lower than what protestors experience today. To fill the gap, I put together a team of scientists. It felt like a second PhD.

I’d always planned to have a career in academic research. But soon after entering grad school, I was repulsed by the prevalence of scientific misconduct. My supervisor taught me how to read a scientific paper, always questioning everything – fabricated results were commonplace. Two researchers working with him had lost a year trying to replicate research on brain development in mice because the original research was so flawed. When students from my institute were struggling with experiments, some people told them they should report false results. Cheating in science triggered me so much that I quit academia and began teaching maths and physics at a local high school. But I never quit researching.

Like learning about scientific cheating, learning about the components of tear gas was very surprising. Historically, Europeans used tear gas in the colonies, so they didn’t care much about its health effects. There aren’t many deaths from tear gas; the concern is more about the progressive effects on your organs from regular exposure. I went back to the activists I’d met while under arrest and told them what I’d learnt. Some continued to believe the president was trying to kill them; some wanted to use my findings for their cause. But for me, this was a public health issue. Some of the protestors helped me in raising awareness, and my work led to health alerts. Soon, both scientists and protesters from around the world started getting in touch.

It’s been liberating to pursue science in my own way: as a mission more than a job

In late 2019, my contacts in Hong Kong started talking about a new virus spreading in the region. ‘Get prepared,’ they told me. There was a general atmosphere of mistrust in Hong Kong because of the extradition bill, and in France because of the crackdown on the yellow vest movement, which made fertile ground for fraudsters and quacks. They advised me to start ‘prebunking’: discrediting myths about the virus before it circulated widely. Many academics are associated with state institutions, they said, and viewed with suspicion in such crises. ‘You are an opposing figure to the government, so people can trust you.’

I decided to try. As COVID-19 cases rose in Europe, I made the rounds of activist and conspiracy theorist shows online, a network I was familiar with because I’d contacted them earlier to talk about tear gas. I pushed back on false information. A French study, about treating COVID-19 with the anti-malaria drug hydroxychloroquine, became very popular around the time and, given my molecular biology background, I became interested in it too. People were desperate to believe in miracle cures, but the supporting research was deeply flawed. I examined the registered clinical trials and took part in a long video explaining the problems with the viral-load results in the paper. Working with other research sleuths gave me hope. There is good science and there are people trying to improve the world.

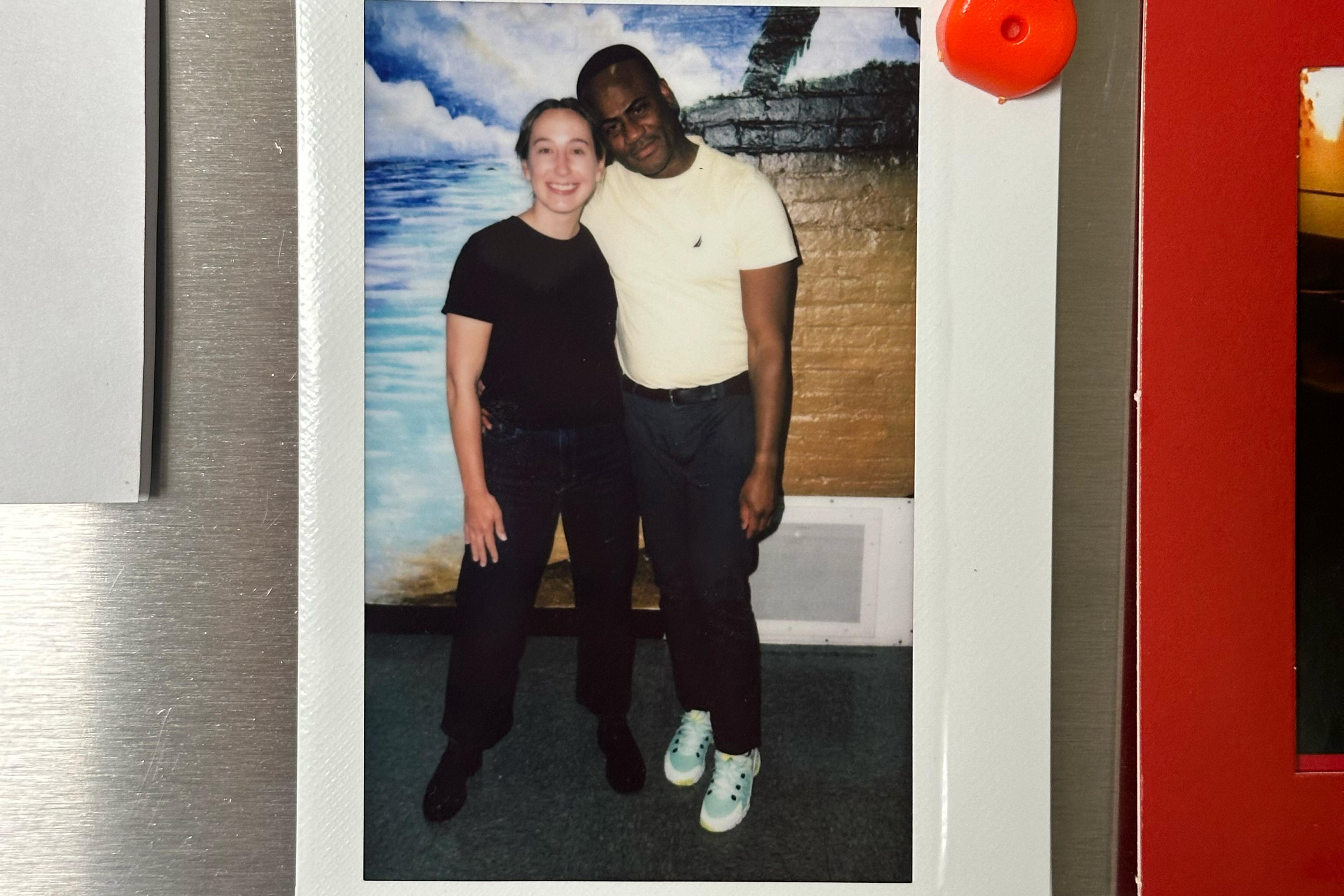

Overall, it’s been liberating to pursue science in my own way: as a mission more than a job. I don’t depend on other scientists to keep my position. But I also don’t have the authority or protection of an institution, and initially many people questioned my credentials. Threats and insults have become commonplace: someone posted my address online, forcing me to install security cameras around my house; others sent letters to the school where I work, demanding I be fired. When I was arrested again following a protest, my house was searched. A prosecutor sued my team for unethical research on tear gas, although we’d gotten written consent from protestors to draw their blood. We won the case two years ago, but the government appealed.

To foot the legal fees, I borrowed money from my parents. It took two years to pay them back. Many of my friends and family were scared. I wasn’t scared for myself, but I did worry for them – I don’t want others to face the consequences of what I do. But although it’s very difficult for them, they do understand. ‘I wouldn’t do it,’ they say. ‘But I’m glad you do.’