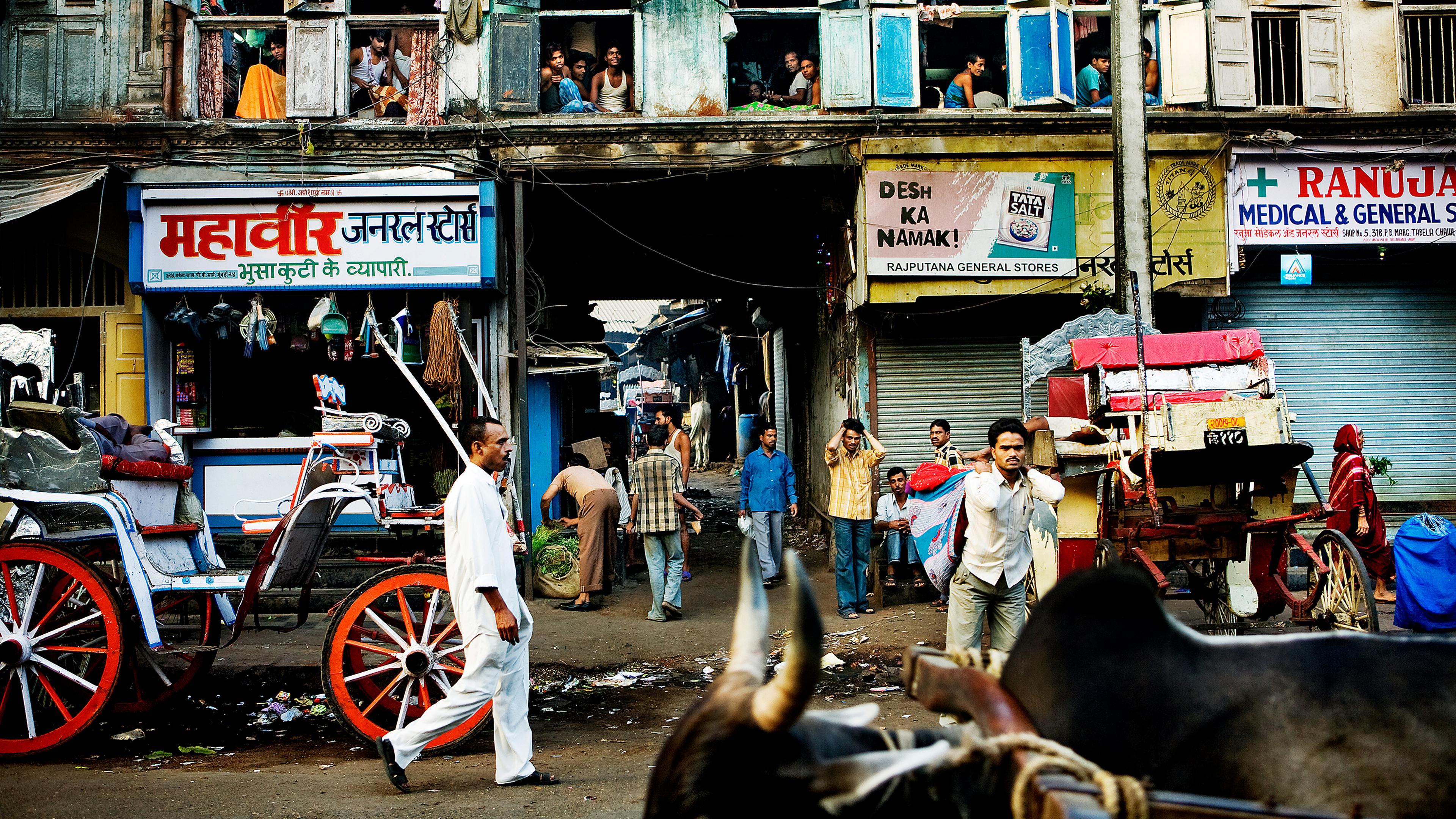

Growing up, I could effortlessly recite all the lines of all the songs from the movie Saagar (1985), because for a long stretch of several weeks, day after day, I couldn’t stop listening to those R D Burman tunes. I had no choice, actually. It was the mid-1990s, when we lived in a town several hours south of Mumbai in a working-class housing complex similar to tenements and known locally as a chawl. Chawls typically housed dozens of families in homes consisting of two small rooms wherein resided each family’s entire universe of people and things. A wide array of activities were communal and public – including public, shared toilets on the one hand and communal music on the other. At some point in my childhood, a neighbour got weirdly obsessed with those fine songs from Saagar, and every day around 10 in the morning she would switch on her tape recorder and play ‘O Maria’ and others at full volume on her very loud speakers. The dose makes the poison even in the case of music: the most melodious of tunes, if heard for too long or repeatedly, will turn toxic. No wonder mornings became quite an aural ordeal during that time in our busy, bustling community.

Chawls are notorious for their crowded living conditions, and in such an intimate group of so many people, there was inevitably a mingling of vastly different personalities from very diverse religious, regional, caste and sub-caste backgrounds. No wonder conflict was always around the corner. However, it was never right in front. My mother would often be frustrated with the cacophony of the Saagar songs, but she never barged into the neighbours’ house to yell at them. When there was a wedding at someone’s home, we heard shrill music and commotion all day and well into the night, but everyone more or less took it in their stride. Smells of all kinds of different foods – often including the pungent air of bombil fish being fried – constantly suffused the air, but no one complained. We were definitely under no illusion that we lived in some paradisiacal land of freedom, but we were still aware that there was a wide spectrum of communal ideas and activities considered acceptable. Put another way: there was, in this and in other similar parts of India – though certainly not everywhere – an abundance of the civic virtue of tolerance (or ‘toleration’, as it is better known in philosophy).

Of course, today, in India and indeed across the world, intolerance reigns, having become institutionalised into an industry, with more or less standardised digital toolkits deployed every day by influential groups to express carefully coordinated and meticulously manipulated offence. I live in the United States now and, among other things, it is disgusting to see how the American state has transformed intolerance against people from Central and South America into a horrible everyday spectacle. Back in India, the state and its rank-and-file supporters have taken intolerance to new heights particularly (and ironically) after many writers and other artists returned their state honours in 2015 to protest ‘rising intolerance’ in the country.

In more recent years, India’s politicians and their street supporters have increasingly and violently attacked the rights of non-Hindu people to pray or otherwise express their religiosity publicly, and have added non-vegetarian food to their list of ‘un-Indian’ things worthy of bans. Every few weeks, one hears of a governmental entity banning the sale of meat and fish, even eggs, for randomly chosen Hindu religious events. As someone who grew up in a community and town where almost every Hindu enjoyed eating meat and fish, frequently as part of their religiosity, I feel both amusement and revulsion at the idiotic arrogance of India’s current politicians. Overall, people with power around the world have indicated that they are not interested in humanity’s collective social battles against the age-old ills of hatred and intolerance and instead will work to normalise, valorise and commercialise those ills in every aspect of public life.

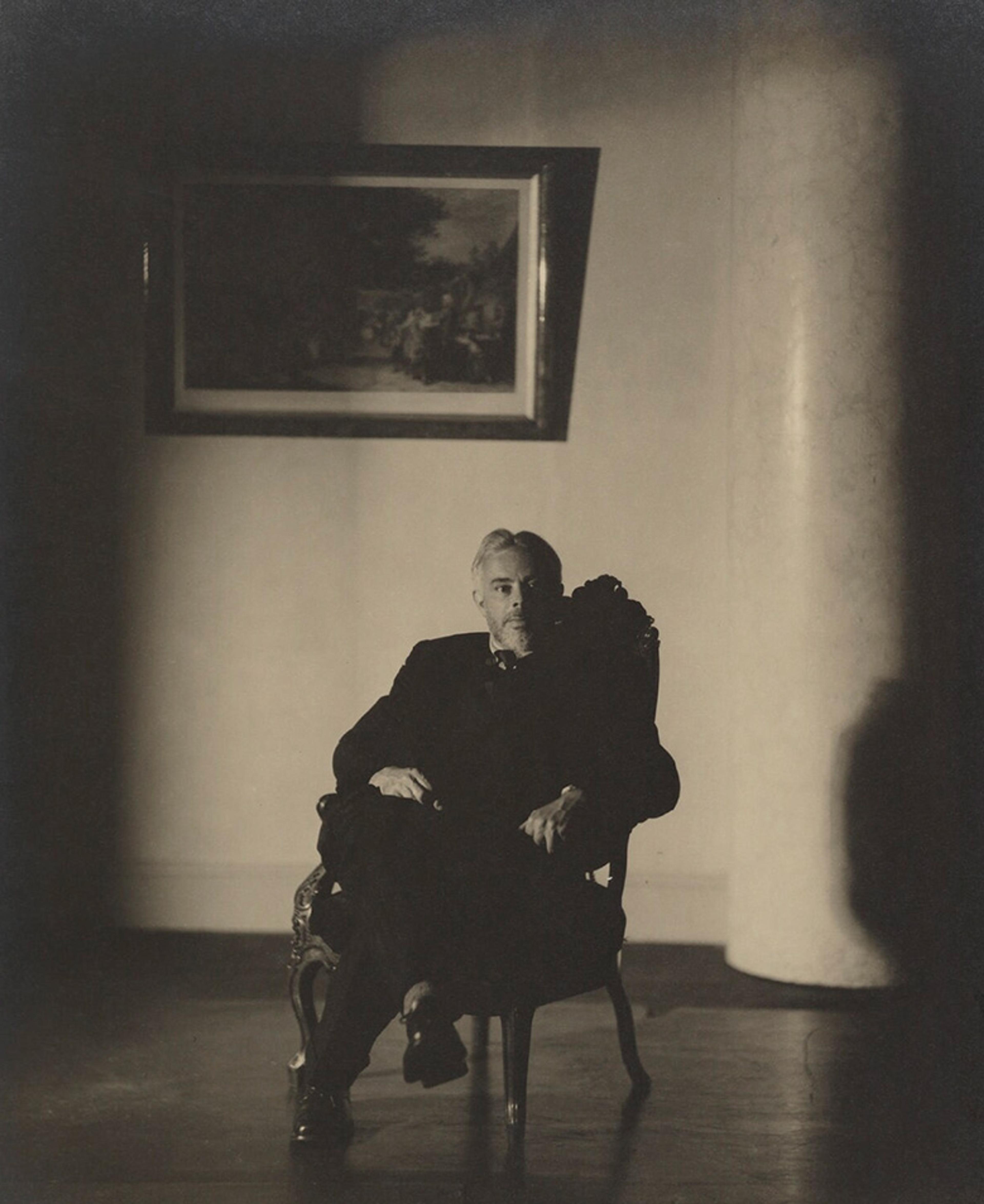

Cyril Edwin Mitchinson Joad by Howard Coster, 1935. © National Portrait Gallery, London

In these times of upside-down morality, I find myself going back to the work of the British philosopher C E M Joad, especially his short book The Story of Civilization (1931). I first read it in middle school (in my chawl home) and have re-read it several times as an adult, finding it more and more enlightening with every reading.

Joad might mock the hypocrisy of self-styled free speech ‘absolutists’ of yesterday

Writing in Britain in the treacherous lull after the First World War, Joad had much to say about the evils of intolerance: ‘a great deal of the misery of mankind in the past has sprung from people being unwilling to tolerate other people thinking differently from themselves.’ Referring to what he considered improved degrees of toleration in British and European society at large in the early 20th century, he wrote that:

[T]his toleration … has come very gradually, and it has only been won after a hard fight. The fight has been not so much to let people think what they liked – obviously you couldn’t stop them doing that – as to let them write and say what they thought. And the permission has only been given very gradually.

Considering that Joad was writing this at a time when officials in British colonies in the Global South were regularly suppressing freedom fighters and their ideas, his optimistic note carries a jarring twang in it. Nevertheless, Joad’s philosophical arguments are worth taking seriously. His definition of tolerance is robust and comprehensive:

A tolerant person is one who does not interfere with other people, even if he thinks they are wrong, but is prepared to let them think what they like and say what they think. If he thinks they are wrong, he may try to persuade them to believe differently, but he will not try to force them.

If Joad were to time-travel to the present day, he might hesitate to consider the contemporary world to be ‘civilised’, which to him meant ‘making and liking beautiful things, thinking freely, and living rightly and maintaining justice equally between [hu]man and [hu]man’. He might find disgusting the fact that many of us do not believe toleration, and its distant cousin empathy, to be important and necessary virtues. He might mock the hypocrisy of self-styled free speech ‘absolutists’ of yesterday who have become the intolerants-in-chief of today. He would most certainly be stunned by the absurd twin-demand from powerful elites that people must be tolerant toward lies and hateful speech, and be intolerant toward truth-telling and empathy for oppressed people.

In his autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth (1929), Mohandas Gandhi refers to a haughty custom in 1890s South Africa: when visiting Europeans, Indians had to take off their turban or any similar Indian headgear, otherwise the Europeans might feel offended. ‘It has always been a mystery to me,’ Gandhi wrote while reminiscing about this experience, ‘how men can feel themselves honoured by the humiliation of their fellow-beings.’ While Joad – writing at roughly the same time as Gandhi wrote his autobiography in the late 1920s – unfortunately did not account for British colonial oppression in his generally optimistic book, he did have something to say about abuse of power and about the intolerance of people and nations who abused power.

The ‘greats’ of European history did not deserve any mention in his book

Joad found discomfiting the widely prevalent belief that a great country or nation is one that has beaten other countries in battle and ruled over them: ‘It is just possible they are [the greatest], but they are not the most civilised.’ As a resolute pacifist, and perhaps also having witnessed the horrors of militarism in the First World War, Joad decried the twisted concept that countries and people need to use violence to bring about peace:

[C]ivilised peoples ought to be able to find some way of settling their disputes other than by seeing which side can kill off the greater number of the other side, and then saying that that side which has killed most has won. And not only has won, but, because it has won, has been in the right.

To Joad, the ‘greats’ of European history like Caesar, Napoleon and Alexander did not deserve any mention in his book because they were simply ‘men who were specially successful in getting multitudes of other men killed ’. He explains: ‘Tyranny has nothing to do with civilisation …’

Joad’s remarkable ruminations on power and tyranny provide an important caveat and lend more balance to his views on tolerance, which might seem unpractically absolutist at first, a problem on which Karl Popper elaborated in his ‘paradox of tolerance’. Tolerance, as Joad describes it, is an essential civic virtue, but does that mean we should be tolerant of lies, or toward speech that calls for violence against someone, or speech that justifies the murder of children? And say we decide we will not tolerate lies and calls for violence: how do we go about implementing such exceptions to the rule? Indeed, what has ailed many societies is not the task of delineating exceptions to tolerance and free speech, which is not that hard – for example, ‘we will not tolerate any calls for harm against any religious group or its followers’ – but the temptation to enforce an asymmetric and unequal application of such exceptions: as when calls for harm against X group are prohibited and strictly punished, while those against Y group are allowed more or less freely with little to no punishment.

When I look back to my old neighbourhood now as an adult, I realise that we had found a remarkably practical resolution to such dilemmas: an unapologetic, wide-ranging practice of freedom and tolerance with minor limits that were well recognised but tacit. For example, when it came to public celebrations of religious festivals, no asymmetry existed: Hindu, Muslim, and Christian families all boldly flaunted and celebrated religious events and freely used public spaces and pathways. There might have been a few families who did not like any kind of public religious celebration, but they exercised tolerance, and so did everyone else when families of a different religion were celebrating. At the same time, there was a mutual understanding that one ‘must not take things too far’: eg, weddings, loud music and other celebrations that went into the night still wrapped up by about 2 am; or while foul language was common, no one used slurs based on religious and caste identities, and if anyone did, there was always someone around to publicly reprimand them. These minor limits on free speech and free expression existed because the adults around me had apparently realised something of which many elites – dealing only in abstracts, without any experience of the streets and the trenches – are totally ignorant: that in any human society, individual freedom will always be as much a social matter as an individual matter; that it is on the bedrock of social toleration that free speech stands tall as an individual privilege.

In most parts of the world today, we don’t think twice before listing freedom as an essential value and as a fundamental right. However, we often forget the other side of the civic coin – toleration – a value so essential that philosophers like Joad considered it indispensable to the ‘story of civilisation’. It is not too late to remind ourselves that, in the absence of tolerance, societies begin to crumble and break down and, before we can even notice it, freedom slips through the cracks.