It was the roller rink party that pushed me over the edge; what I had previously feared, I came to loathe. I was nine, and it was my birthday, but I couldn’t skate. Instead, from a table sticky with dried-on slushie, I watched my friends circle round and round, a cold pack numbing the angry lump on my foot. As I slept the night before, a rogue spider, probably disoriented and tangled in my sheets, had bitten me. My overactive immune system took offence, and suddenly I was benched.

Yes, I still had fun. There was cake and there were gifts, and all of my friends packed into my parents’ 1986 Chevrolet Suburban. I went on to have more parties. However, while I had always been terrified of spiders, that day taught me that they truly are dangerous, and – especially when they are in your house, or God forbid your bed – must be eliminated on sight.

While I don’t, philosophically, like the idea of killing anything, practically, I wasn’t willing to make exceptions. I tolerated insects and other bug-like creatures outside, but if a creepy-crawly was in my space, it was trespassing, thus fair game.

Most of the time I was too afraid to do it myself. I had the (certainly irrational) fear that whatever spider I was trying to murder would bite me through the wad of Kleenex, no matter how large. If there was anyone else home, I would beg them to execute the kill. If I was alone, I would use the whole tissue box or a shoe as my weapon. And if a spider went missing after an attempted squishing? A guaranteed sleepless night.

After having a child, I became even more ardent. After all, I had to protect my baby. Yet, as my child grew, they started to question my perspective. Why does any creature deserve to die? Even if it bites you, you’ll be fine. Spiders have way more to fear from you than you from them. My precious child wanted me to trap and relocate spiders to the great outdoors, to gently guide the ant army invading our pantry into retreat, to give flies the opportunity to find their own exits. I tried to explain that I was killing only the bugs that were where they shouldn’t be, the ones that would harm us by eating our food (and maybe take a bite out of us along the way).

When a tiny daddy longlegs showed up in my bathroom, I did nothing

Anyone who’s been around kids for any length of time knows they will make you question even your deepest-held beliefs. And since the authoritarian because I said so works only so many times, eventually I had to admit that my actions were based less on reason and more on abject terror. So I made a compromise. If a bug or spider was harmless, I would do everything I could to either leave it alone or shepherd it outside. I would impose the death penalty only if there was a legitimate risk to our safety.

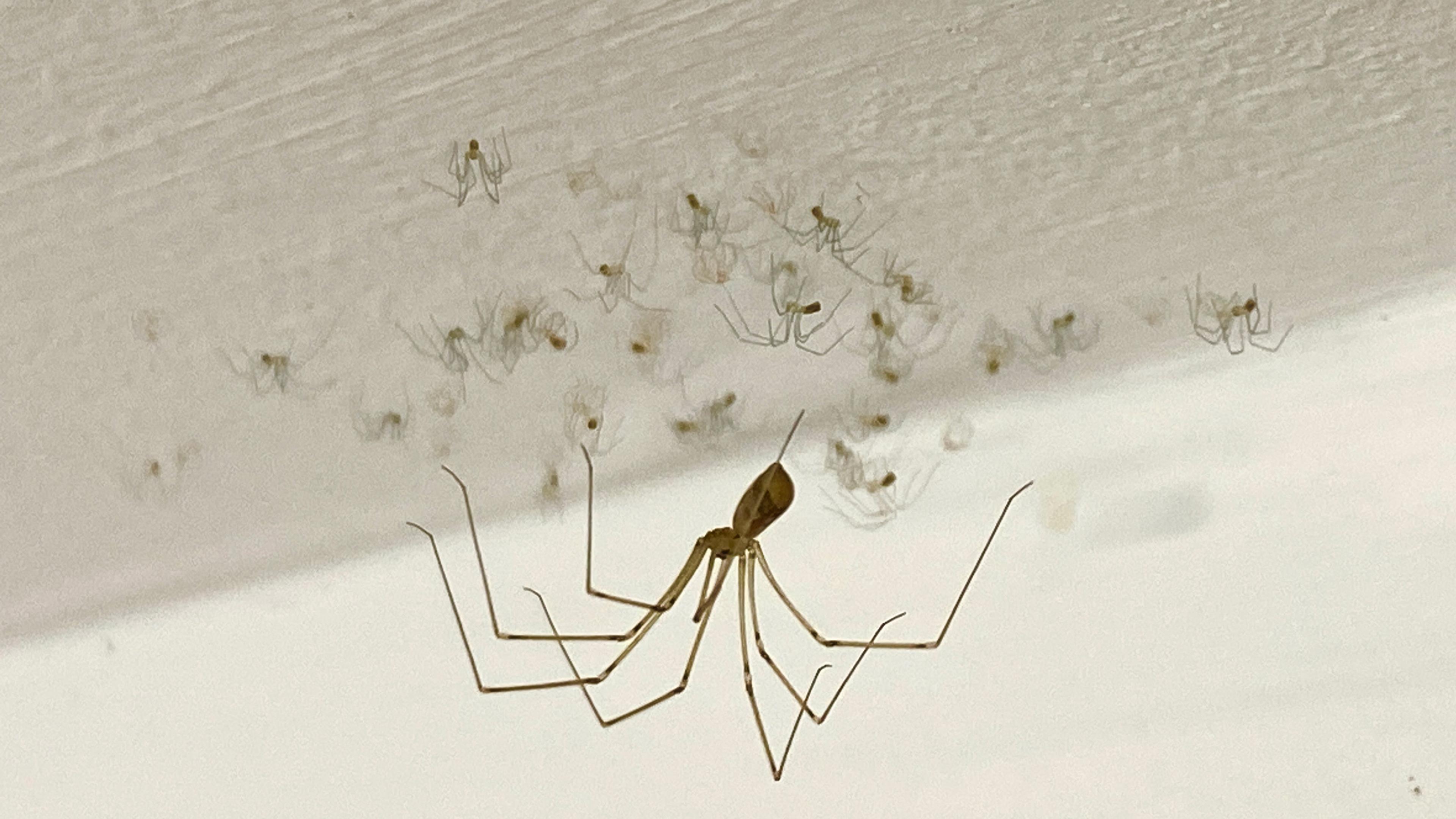

So when a tiny daddy longlegs showed up in my bathroom, I did nothing. It soon made its home in the corner by the sink, hiding during the day and hanging out in the little web it repaired each evening.

I had always heard that daddy longlegs are extremely venomous to their prey, but that their fangs are too short to bite humans. This is a common myth, but it is just that, a fiction. In fact, the name daddy longlegs is widely used to refer to a number of different creatures with different biting capabilities, some of which aren’t even spiders.

True daddy longlegs are actually long-legged harvestmen, ground-dwelling arachnids that live outdoors. They are not spiders at all, as they have only one body section (spiders have two), two eyes (most spiders have eight), and a segmented abdomen. They also don’t make webs, instead dwelling under logs and rocks and, as they have no venom, fangs or other means of subduing prey, subsist mostly on decomposing plant and animal matter.

On the other hand, the label also refers to ‘daddy longlegs spiders’, which is what my new bathroom friend turned out to be. These arachnids, also called cellar spiders because they are often found in dark corners of houses, spin silk and make webs in sheltered, out-of-the-way crevices, snaring insects for their meals.

Regarding their venom and fangs, daddy longlegs spiders are venomous, but the venom is not that potent, even for insects. They do have tiny fangs that are capable of piercing human skin, but their bites do little to us aside from stinging for a moment. It turns out that even though they have all of the spidery traits that make me cringe and shiver, neither outdoor harvestmen daddy longlegs nor daddy longlegs spiders pose any sort of danger to humans, and having them in the house may keep mosquitoes and other pest populations at bay.

The first time I noticed her, she caused me to inhale sharply and choke on the toothpaste on my brush

After a few days, I stopped startling every time I entered the bathroom. I began to expect that, as the sun began to drop, so did the daddy longlegs, spooling down from its preferred daytime perch clinging flat to the bottom of the medicine cabinet, and beginning its nightly web repairs. Typically, it would string silk between the vanity unit and the wall, forming a small sticky triangle to trap any gnats or tiny flies that might happen through.

I soon noticed that she was growing larger by the day. She was probably about a centimetre across the first time I noticed her, when she caused me to inhale sharply and choke on the toothpaste on my brush. Weeks later, with the speck of her body rounding and her legs out straight, she neared the size of a bottle cap.

After a while I named her, though I can’t remember now what I chose, perhaps Trixie. I grew used to checking each morning to make sure Trixie was tucked up under the cabinet. I watched her weave each evening as I readied myself for bed. I began to take care not to splash water when I washed my face, because if a rogue drop did find its way to Trixie’s web, it seemed to shake her.

A bit of research revealed that this is actually a defence strategy: when disturbed in their webs, daddy longlegs spiders respond with a fast, vibratory motion that blurs them to nearby predators and further entangles struggling prey. I realised that, had I moved Trixie outdoors, she probably would not have survived; she had adapted to be indoors. She knew instinctively how to both protect herself and to thrive where predators like me loom large and prey is hard to come by, but she would be ill-suited to weather the elements outdoors.

One evening several weeks into hosting Trixie, I went to get ready for bed and didn’t see her. I thought it was odd, but also, it was on the early side so maybe she just hadn’t gotten to spinning yet. I bent to peer under the medicine cabinet and saw nothing. And then I realised: we’d had some cleaners in that day, and I hadn’t mentioned Trixie.

My heart beat fast. I found myself hoping that she had hidden away and would come out in a day or two, not wanting to believe that she was probably dead and gone. I was bargaining in my head while peeking into each nook and cranny in the bathroom. The loss of Trixie twisted in my gut. It was my fault she was gone, and while I didn’t exactly miss her, I felt bad that I hadn’t protected her. She had become familiar, and I felt her absence. What had happened to my spider-hating heart?

I found a kind of kinship with this creature simply by being curious and open to sharing space

What started as an uneasy détente in that bathroom had become a full-fledged bond, at least from my end. It turns out that not only was I attached to Trixie specifically, but I am no longer repulsed by daddy longlegs in general. I may even be a bit fond of them. I now allow them to manage the insect population in the garage, and when one chose the crown moulding in the living room as its hunting ground, I let it be until it moved on.

This about-face came not just because I realised daddy longlegs can do me no harm, but also because I have lived alongside them. It turns out sharing a bathroom with Trixie, adapting to her presence, and becoming accustomed to her daily routine generated enough empathy to overcome my fear of her. Not only was I objectively desensitised to my phobia through repeated exposure to her appearance, but I found a kind of kinship with this creature simply by being curious and open to sharing space.

Trixie did not evoke a full transformation. I still loathe most spiders. They still terrify me. Last night as I was taking out the trash, a black, leggy arachnid skittered across the lid. I panicked and knocked the whole barrel over. In that moment, though the spider was outdoors where it ‘belonged’, I still wanted to squash it. But I didn’t.

There’s no shortage of things to fear in this world – many of them genuinely dangerous. But often, fear arises less from real threat than from unfamiliarity, from the sense that something or someone is ‘other’. When we take the time to understand what unsettles us and forge a connection with it, we may find our anxiety easing – and our bond to the world, both inside our homes and beyond, growing stronger.