At 5 am, a correction officer (CO) flipped on the lights in our warehouse-like dorm. ‘BAKERY!’ he shouted at the top of his lungs, waking up nearly 50 sleeping inmates, although it applied only to about eight of us. While the rest groaned and went back to sleep, we rushed to wash our faces, brush our teeth, and get ready to make bread for all of Rikers Island, a 413-acre jail complex on the East River in the Bronx, and for the rest of New York City’s jail system.

At 22, I was probably the youngest inhabitant of 8-Upper, my housing unit. T, who slept on the bed to my right, liked to joke that my three-month sentence for reckless endangerment was basically me ‘visiting for the weekend’. He had been transferred from an upstate prison to finish the last year of a three-year sentence. That’s where the real bad boys lived, he said, many of them for the rest of their lives.

‘HURRY UP, INMATES!’ the guard yelled, even though only eight minutes had passed since he’d screamed us awake. ‘We’re late,’ he insisted, herding us into a single file that became longer as inmates from other housing units joined. At the uniform changing station, we took turns changing from our green scrubs into orange-and-white striped jumpsuits and black rubber boots, before boarding a van for the bakery.

The 11,000-square-foot complex wasn’t a typical bakery at all. For one, it was encircled by double rows of barbed wire. ‘Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread’, read a sign in Gothic script. ‘Count Blades’, read another in bold letters, this one in the warden’s office, reminding the civilian supervisors of the type of employees they were managing. ‘This job is really a privilege,’ the deputy warden in charge told us as we ate the jail’s continental breakfast: a single-serving cereal box, a 4-ounce milk carton, a slice of bread with a scoop of jelly. Her statement made me laugh, because the administration had told me I didn’t have a choice when they signed me up to make thousands of loaves of wholewheat bread every day.

Before I set foot on Rikers Island, I had viewed blue-collar jobs as someone else’s destiny and beneath me. My mother was a self-made woman who moved me and my siblings to the United States from Latin America when we were children; despite this, I acted like privilege was my birthright, shrugging off accomplishments as proof of genius rather than earned through my single mom’s painstaking efforts to offer me a life technically not meant for me. When I pleaded guilty to reckless endangerment, I knew I’d put myself in a position to betray all her work.

Unlike many of my fellow inmates, I believed I deserved my sentence. I’d made the worst mistake of my life and desperately wanted to put it behind me. But as I served out my 90 days, I stopped thinking of ‘criminal’ as a blanket identity. Every record carried a nuanced backstory – if also an often all-too-familiar one, like T’s aggravated assault. He’d beaten up someone for smacking his wife’s ass on the subway, his sentence worsened by prior drug convictions and being Black. As for me, I often ruminated on how I might have avoided jail entirely had I been able to afford a private lawyer or faced a far harsher punishment if I weren’t a fair-skinned Latino with a full-ride at a top university, working part-time at a leading real estate firm.

T wasn’t allowed to work but he’d told me the most fun job at the bakery was mixing flour. Each morning, when the warden and her blue smurfs barked out assignments for the day, I volunteered for that role, which involved operating a human-sized beater. ‘That’s cute,’ she said of my proactiveness, before directing me to the storage room, to load carts of loaves into delivery trucks. It wasn’t the worst of the tasks. Although all were tedious and required muscle and mindless focus – some inmates saw the bakery as a way to get in shape – that distinction belonged to transferring bread from the conveyor belt into the pit of hell that was the oven, then loading the now-scorching trays onto carts for storage – dangerous, miserable, and back then still paying only $0.67/hr.

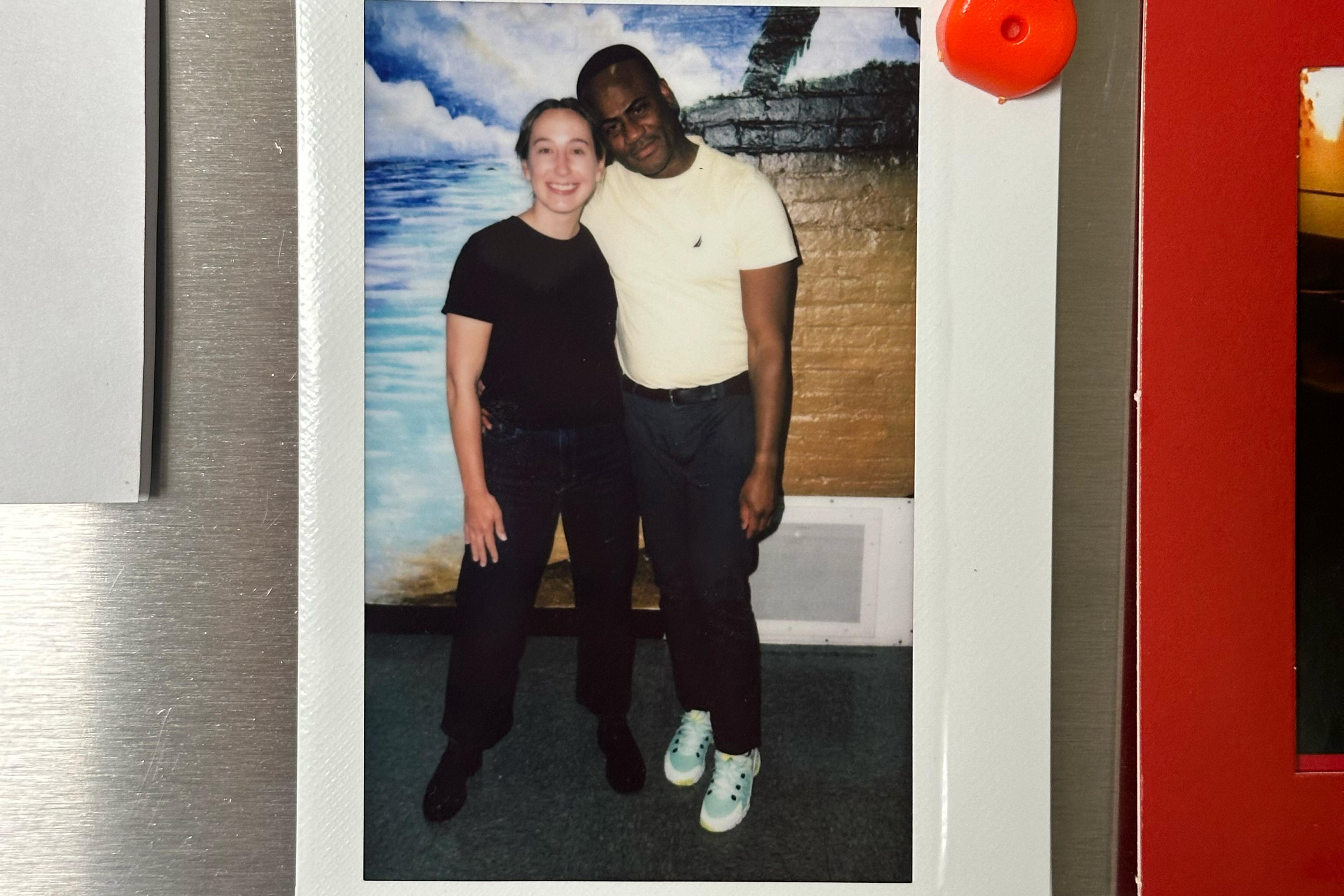

My mother was happy to see my popularity transferred from high school to jail but not exactly proud

At noon, an inmate on the kitchen staff rolled in with a metal cart loaded with hot plates. One of us bakery workers would run to get a freshly packaged loaf of bread, tearing it open and handing out warm slices to everyone. We all ate it with pleasure. It beat a lot of the bread you could buy in stores. I couldn’t help but think of the physical effort gone into making it, and the millions of manual labourers across the country and the world who did such work for a living. They were paid more than us, but not enough.

Whenever hamburgers or hot dogs were served for lunch, I’d stare at the meat on the Styrofoam plate and think of my poor abuela, whom I used to terrorise with my picky eating habits as a child. ‘What’s the difference?!’ she’d beg when I refused to eat if the wrong type of bread was served with our meals, as if starving myself punished her. Now, as I placed the single patty between slices of wholewheat bread and scarfed it down, I wished I could tell her it didn’t matter. She was still alive, but didn’t speak English and was too old to understand the automated phone warning – ‘an inmate is calling’ – or how to press 1 to speak to me. Instead, I’d call my mother who’d be shocked whenever T playfully took the phone and said: ‘Hi, Mom.’ She was happy to see my popularity transferred from high school to jail but not exactly proud.

Baking would finish at 1 pm, and we’d spend the rest of our shift cleaning and prepping for the next day. I tried quitting a couple of times because I wanted to chill in the dorm with T, who always found ways to smuggle tobacco and had a solid workout routine: push-ups on the floor, pull-ups using the bathroom stalls, and lifting stacked chairs as dumbbells. But the administration threatened to take me out of 8-Upper, so I stayed, mostly because having T as a friend made me feel safe. I once asked him how to get out of working, and he told me I’d need to cause trouble. The next day, I looked around the bakery and accepted I’d spend the rest of my sentence there. I was led to jail by my knack for drinking, not by rebellion.

At 3 pm, a CO would escort us back to the dorm – just in time for quiet hour. The TV in the common area was switched off and games put away; everyone had to sit on their own bed and use the time to reflect, like nap time for grown men with tattoos, facial hair and potty mouths. By 5.30 pm, a CO yelled the last ‘CHOW!’ – what mealtimes were called, whether breakfast, lunch or the dinners served at senior citizen hours.

Many of us would be starving again by 7 or 8 pm. Circles of temporary friends pooled together commissary items to prepare meals, each with a self-assigned head chef. As someone who didn’t really have any close friends – I mostly kept to myself for fear of being outed as gay – I used this time to bury my nose in a book and stuff my face with oatmeal and peanut butter, trying to forget I no longer had autonomy over meals.

He liked my energy, he said. He facilitated the small joys I found on Rikers

One night, T’s tall, muscular shadow hovered over me unexpectedly.

‘Got any mackerel?’ he asked.

I handed over the packaged fish to him like a drug exchange. He grabbed his storage-bin top as a counter and crushed dry ramen on it with the bottom of his brown bowl, then placed the crushed ramen inside a plastic bag. Next, he added torn-up pieces of beef jerky, two pouches of mackerel, and handfuls of crushed BBQ chips.

Some housing units at Rikers offered a closely monitored water hotpot that all inmates shared, signing it in and out after each use. Often, in the evening, people would queue up to use it. For some reason, no inmate stopped T from skipping the line. Most of them seemed to fear him – even the COs gave his antics a tolerance they neglected to show the rest of us – but he was exceptionally kind to me. He liked my energy, he said. He facilitated the small joys I found on Rikers: how to use a battery and the wire wrapper from a loaf of bread to spark a light for smoking tobacco; how to throw a bedsheet over the top ridge of the doorless bathroom stall to get some coverage. Better to have no top sheet, he joked, than no private shit.

‘Yo, T, you wanna get in on this?’ someone waiting his turn hollered from behind us.

‘Nah,’ he responded without glancing up.

He filled the bag with boiling water, wrapping it up the way you’d hold a goldfish. After approximately five minutes of ‘cooking’, he poked a couple of holes in the bottom of the bag, holding it over the bathroom sinks that inmates used to wash hands and underwear. ‘Cool,’ he said, pleased with the results. ‘I also swiped hot sauce from the CO’s lunch.’

I motioned a chef’s kiss that he didn’t understand, so he jokingly called me a fag. I tried my hardest not to seem scared by the word. Internally, I beamed with relief for blending in.

As T and I sat down to eat, I glanced around at this most unhinged and motley collection of concurrent dinner parties, and felt an unexpected warmth. When I first entered Rikers, I’d been worried about how I’d survive 90 days among men labelled unfit to live in society. I hadn’t expected most of them to be nice, determined to hold on to their humanity through laughter and shenanigans. I certainly hadn’t expected I would be enjoying impromptu late-night dinner with a friend. I said a silent prayer that, in the future, the outside world would see the value we all bring to the table rather than where we’ve sat.