Throughout his short documentary Raised by Krump, the Swedish-American filmmaker Maceo Frost, the son of a skateboarder and a streetdancer, circles and underscores the notion that, beyond being a freestyle street dance, krump is a way of life. More specifically, he emphasises how it has both uplifted and brought up the dancers featured in the film. Transcendent experiences, communal bonding and powerful forms of self-expression are just a few of the forms of uplift that krumpers experience in dancing. But there’s something unexpected in the idea of dance itself providing nurture and care in ways typically associated with childrearing.

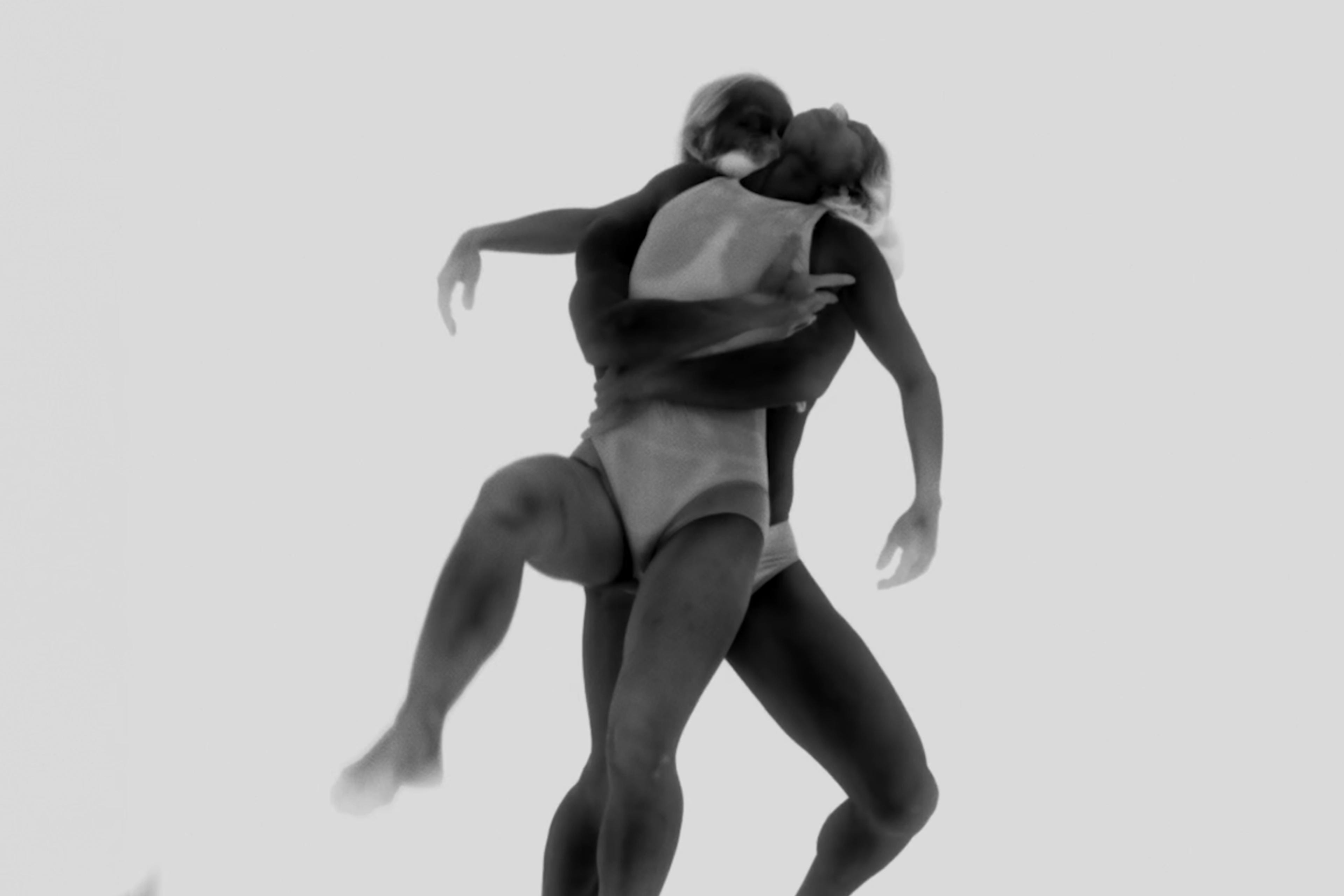

Although krump is most often a battle dance in which members of different crews face off against each other, Frost keeps a tight focus on the personal experiences of dancers rather than on the external trappings of competitions. He weaves these testimonies through a perpetually kinetic flow of dancers on stage, on the street, at home and in ecstatic states of performance, creating a rich sense of how krump suffuses their lives. Slow-motion sequences, off-kilter camera angles and bracing shifts in music not only accentuate the dynamism of krump, but also act as visual and aural proxies for the experience of krumping itself.

Krump emerged in South Central Los Angeles in the early 2000s, its characteristically frenetic, aggressive moves inextricably tied to the poverty and violence that still weigh so heavily on those neighbourhoods. The dancers in the film, including some of krump’s creators, make clear how they see it as a response to struggle, loss and death. One extended sequence features a dancer incorporating gestures that explicitly reflect his harrowing story, at once personal and indicative of what it’s often like to be Black and poor in Los Angeles.

More than a representation of hardship and suffering, however, all the krumpers speak of dancing in ways that evoke a healing power – it’s therapy, salvation from pain and danger, an expression of feelings they can’t put into words, and a way to make room for emotions they’d otherwise try to shut down. Their clarity and candour about krump’s restorative qualities almost have the ring of gospel.

The film’s central refrain, ‘Krump raised me’, stated by different dancers in varying ways, has a straightforward connotation for individuals who grew up without, or lost one or both, parents. But what’s compelling is that all the dancers also feel raised by krump in a sense that’s deeply internal, and not just a feeling of belonging to a community, though that’s undoubtedly important.

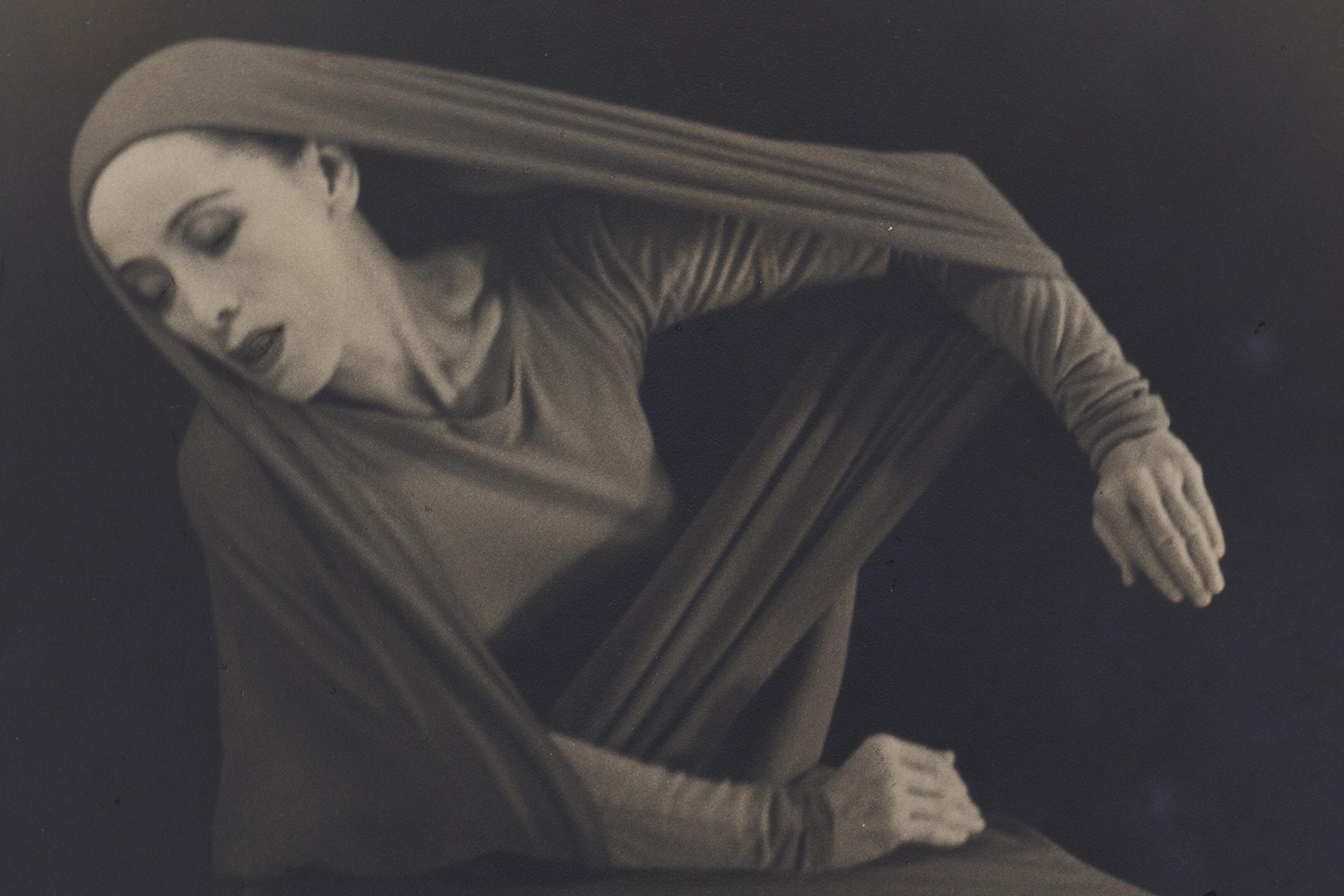

They describe krump as both something that they do and something that transcends them. It is simultaneously a profound personal expression and a force that guides, protects and nurtures. The specific manifestations of this force are diverse – learning how to cry and work through emotions, being able to understand other people’s states of mind, or finding shelter from danger. But because the dancers understand krump as emerging from within, these benefits of krump as caregiver seem to derive from a kind of embodied mysticism – a spirituality of expressive movement.

Writing in Aeon on why humans dance, the philosopher, dancer and scholar of religion Kimerer LaMothe posits that ‘every dance technique or tradition appears as a stream of knowledge … dancing provides humans with the opportunity to learn how their movements matter.’ It’s an exciting proposition – that krumpers create with their bodies knowledge that’s deeply nurturing for their selves. The words of the writer, feminist and civil rights activist Audre Lorde offer another way to think of this knowledge. In 1988, she wrote: ‘Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.’ Though krumping might not have been born of political parents, it can perhaps be understood as a form of radical self-care.

Written by Kellen Quinn