Often, forgetfulness is a mere inconvenience: that name, date or task that simply slipped through the cracks. But, sometimes, it’s downright unsettling to forget something. A friend asked me the other day: ‘Remember that hilarious dinner we had there a few years ago?’ And when for the life of me I couldn’t, I felt as if a slice of my existence had been cast into oblivion.

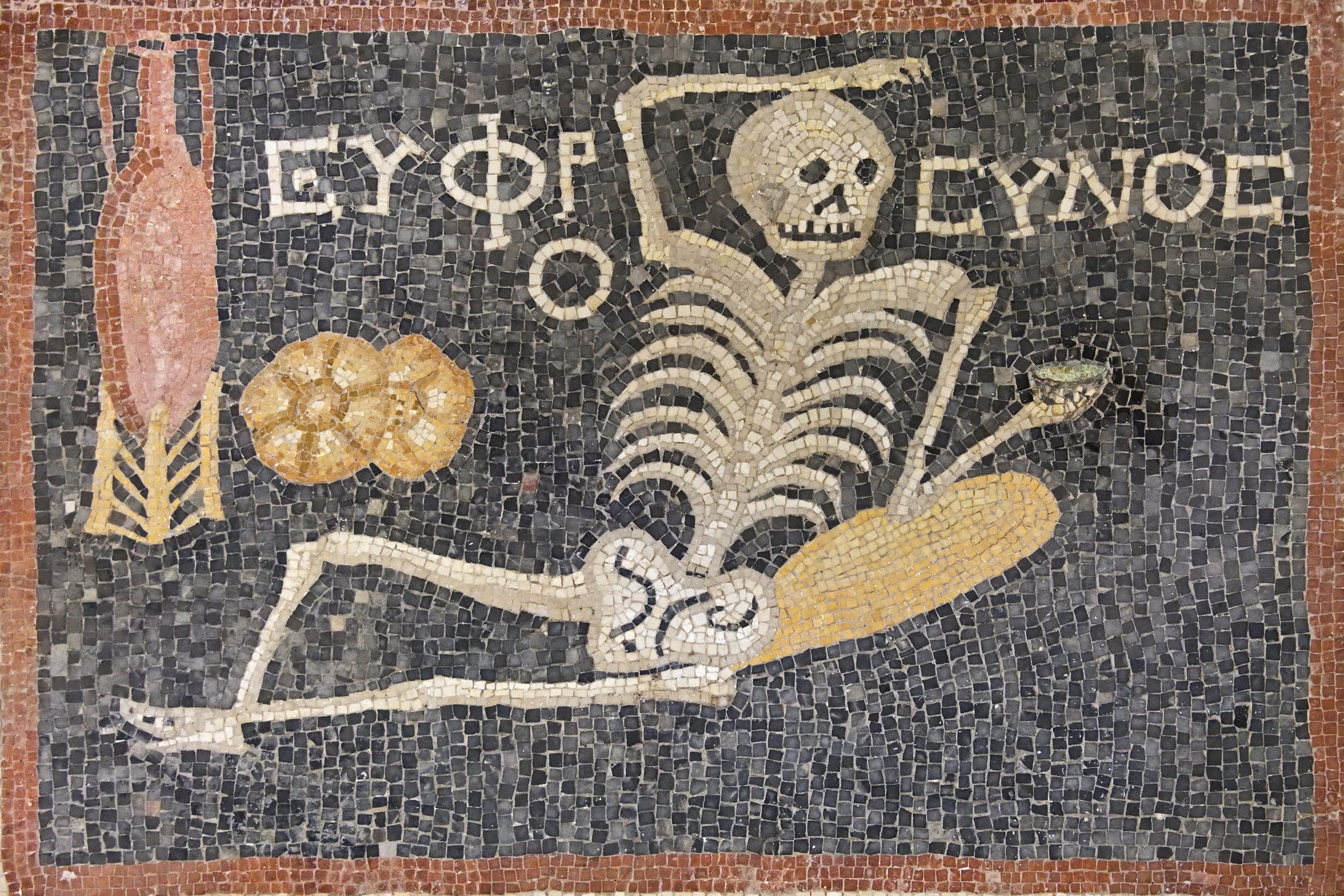

The ancient Greeks harbored a similar, if more pronounced, terror of forgetting. Plato associates forgetting with ‘non-being’, nothingness. Homer’s heroes do heroic things in order to achieve kleos (fame), and thereby defeat the destruction that comes with being forgotten. (As one of the Seven Wise Men said: ‘You will obtain memory through deed.’) Perhaps as a kind of buttress against the fear of forgetting, they anointed Mnemosyne, memory, the mother of the nine muses.

But I enjoyed learning the other day that this negative view of forgetting wasn’t shared by all ancient peoples. Daoism positively celebrates forgetting, indeed raises it to the status of an art. Zhuangzi, a founder of the tradition, urges people to master this art in order to gain a glimpse of Dao (the way), the eternal substratum of our passing world. As the philosopher Xia Chen writes, Zhuangzi’s idea is that the more of the world we’re able to forget – be it morality, history, the arts – the more we’re able to discover our true self, shaving off all that’s inessential to get down to the pith that we ultimately are.

Now, I don’t know if that will be of help when I inevitably confront the next lost memory, but it’s good to remember, if possible, that there’s a certain, subtle benefit in forgetting. ‘Only by forgetting,’ wrote the German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer, ‘does the mind have the possibility of total renewal.’