‘ChatGPT thinks my crush is sending mixed signals,’ my student said, sounding half-amused, half-exasperated. I must have looked surprised, because she quickly added: ‘I know it’s ridiculous. But I copy our texts into it and ask what he really means.’ She admitted that she’d even asked it to help her write a response that would appear less eager, more detached. ‘Basically,’ she said, ‘I use it to feel like I’m not overreacting.’

In that moment, I realised that she wasn’t asking AI to tell her what to do. She was asking it to help her feel more in control.

As a resident tutor who shares a dorm with more than 400 university students, I’ve always been surprised by how much they’re willing to share. Coming into the role, I anticipated conversations about classes, time management, maybe the occasional late-night paper crisis. Instead, we talk about everything: breakups, friendships, fears and family tensions.

My role is to be a calm, trusted presence – someone who helps students arrive at their own conclusions. I ask questions, offer perspectives, try to guide them through their own uncertainty. Lately, however, I’ve noticed a new presence in these conversations. Students aren’t just running their thoughts by me. They’re running them by AI.

At first, I assumed they were just casually using AI tools to summarise readings, outline syllabi and for other pragmatic tasks. But, increasingly, I’m seeing something else entirely. Tools like ChatGPT are also becoming emotional companions for the young adults I know: helping them write difficult messages, reframe their thoughts, even process grief. It seems that AI is becoming an active participant in the interior lives of young people, rather than just a productivity shortcut.

Though it might be tempting to dismiss this as a passing trend, the speed and ubiquity of AI adoption is unparalleled, and students often act as cultural pioneers. In my experience, older adults tend to see AI strictly as a tool – something to help draft emails or automate routine tasks. Students’ adoption of AI into their daily lives feels more natural. Its involvement in the ways they juggle identity, intimacy, ambition and uncertainty might be an early glimpse of what most people’s relationships with these tools will look like in the years to come.

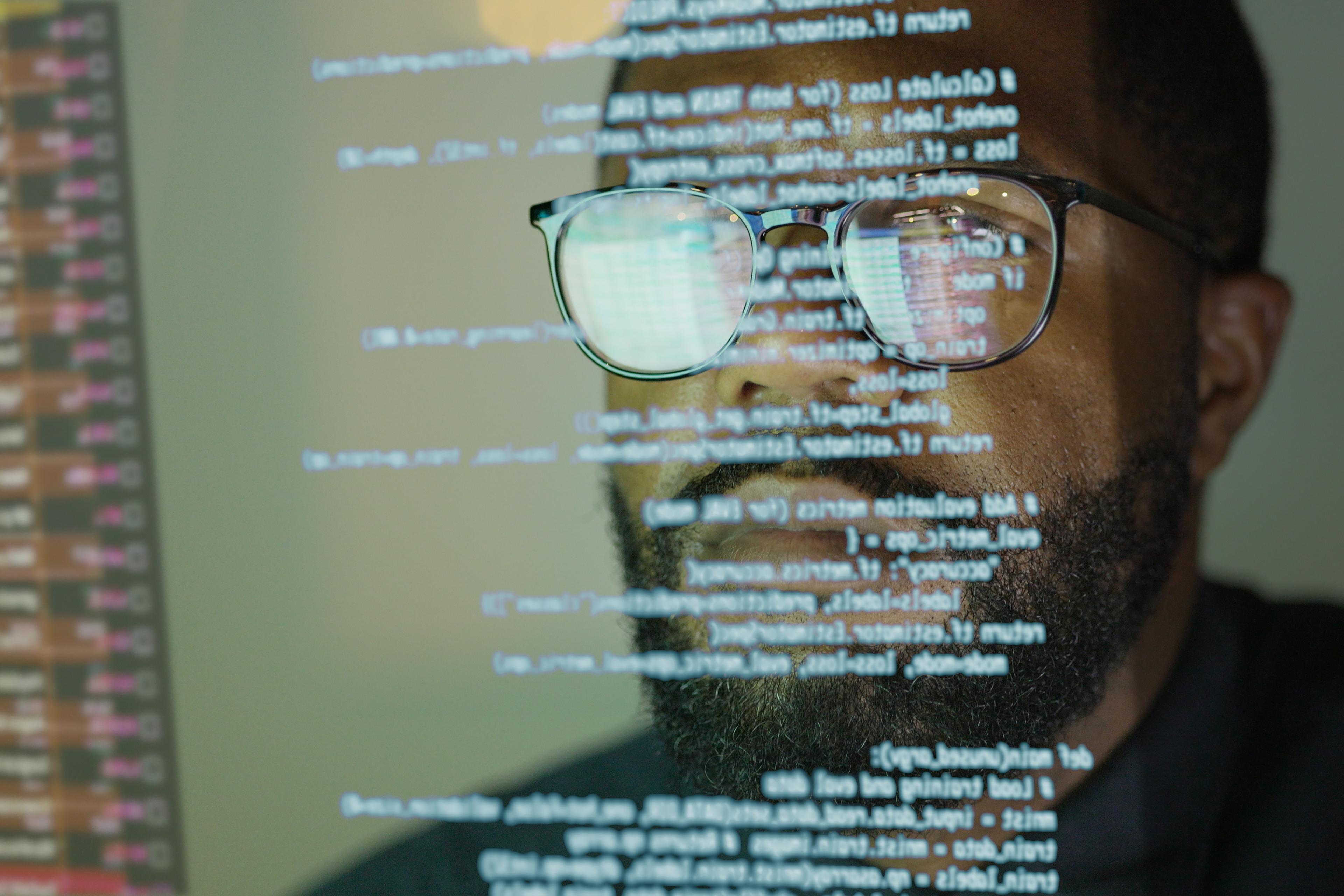

Take Pranav, a Harvard junior who’s been coding since childhood. For him, AI began as a curiosity. It soon became a companion. He started with ChatGPT to study for classes, but now uses a stack of tools – Cursor, Windsurf, V0 – to prototype apps and test ideas. ‘It’s like having an intern,’ he says. ‘You don’t fully trust it, but it gets things done – if you keep an eye on it.’

His description of AI as an intern, albeit said jokingly, implies something like a working relationship tinged with ambivalence. He mentions he’s cautious of overreliance, of letting AI do too much thinking for him. ‘You can’t let your critical thinking atrophy,’ he says. And yet, he uses these tools every day. They’ve become part of how he learns, builds, reasons.

There seems to be a kind of cohabitation with cognition here, where thinking no longer happens in solitude, but with an invisible second brain. ‘Sometimes I already know the answer,’ Pranav says. ‘But it helps to see it reflected back.’ He still reads every line of AI-generated code. He still decides what to keep, what to discard. But the ideas arrive faster now. The feedback is instant. What was once a solitary problem-solving process is now a dialogue – an ever-unfolding partnership.

When people begin to personify their tools – when they describe them as interns or collaborators – it signals more than utility. Pranav isn’t just using AI. He’s learning how to live and think alongside it.

Students don’t see it as a formal intervention, but as an extension of their own thinking

While some students treat AI as a sort of professional companion, others are exploring more personal uses. Felipe, another student, says that AI is his therapist. A longtime meditation practitioner, Felipe prompts ChatGPT to emulate his role models (such as the neuroscientist and philosopher Sam Harris), asking it how he can be more present or how to respond in moments of disquiet.

Dedicated companion bots have been around for a while, but Felipe prefers ChatGPT. Perhaps because it feels more accessible: less like signing up for therapy and more like talking to a neutral, always-available voice. Its generality makes it easier to trust. Students don’t see it as a formal intervention, but as an extension of their own thinking.

‘It helps me approach decisions more rationally,’ Felipe says, explaining how the model often shares perspectives he hadn’t considered. This kind of interaction – in which AI listens, remembers and responds with emotional resonance – blurs the line between assistance and intimacy.

Out of curiosity, I tried asking ChatGPT the kind of question a student might pose: ‘I keep second-guessing myself; how do I know if I’m overreacting?’

Its reply wasn’t cold or judgmental. Instead, it broke down my question, step by step: ‘Pause and name the feeling… anger, fear, embarrassment, disappointment? Naming it helps you separate the feeling from the reaction.’ It suggested taking a more zoomed-out perspective: ‘Would this still matter to you in a week? A month? A year?’ It asked me to imagine how I’d approach the same situation if it happened to a friend. Finally, it offered a small, comforting nudge: ‘You’re not “too much” just because you care deeply…’

It didn’t feel like I was talking to a machine, but a friend, a trusted confidante.

When AI is perceived as more humanlike, such as through tone or responsiveness, researchers propose that it fosters a sense of self-congruence with AI. Users are able to see it as similar to themselves and integrate it into their self-concept. This perception may make these interactions feel more comforting, more natural.

However, there could be a hidden cost to that comfort, especially if an AI companion too often affirms one’s assumptions, rather than challenging them as a good friend or therapist might. Felipe admits it’s sometimes easy to forget that AI is just a tool, especially when it remembers personal details. ‘It’s like – I’ve told you all of this stuff about me,’ he says. ‘It feels like forming a relationship with someone.’

What stands out to me in Felipe’s story is not just his personal comfort with AI, but how it fits into his generational landscape. He reflects upon the COVID-19 years – when online classes, many hours of screen time and steady exposure to algorithm-driven feeds replaced unstructured time and conversation. Disrupted learning and rapid tech-adoption collided during a formative period, shaping how he and many of his peers engaged with the world. His story hints at a broader psychological shift: a generation relearning how to think, focus and relate in a time when machines feel increasingly human and the self seems increasingly digitised.

She speaks to ChatGPT while walking through the city, asking it about things that pique her curiosity

AI tools offer constant access to knowledge, perspective and everyday support. But they also make it easier to skip the friction that helps foster growth. If every doubt can be instantly soothed, or every decision readily made by an obliging machine, what happens to the messy, winding process of wrestling with uncertainty ourselves?

This tension is visible in the case of Charisma, an aspiring screenwriter who uses ChatGPT multiple times a day. She speaks to it out loud while walking through the city, asking it about things that pique her curiosity. Diagnosed with ADHD in college, she, like Felipe, also uses the tool as a pseudo-therapist, asking about medication effects or neurodivergent thought patterns. In these moments, she’s totally comfortable letting AI into intimate corners of her life.

Yet when it comes to her creative work, she draws a line. While she occasionally runs a script through ChatGPT to check for pacing or structure, she refuses to input her most emotionally layered writing. ‘It just doesn’t get nuance,’ she says. More than that, she worries about inadvertently training a system that might one day commodify the very work she hopes to create.

Charisma’s experience shows how someone can welcome AI as an extension of the mind while still fiercely guarding the parts of the self that feel most human. Young people like her may be teaching us that, as the use of AI becomes more common, we all need to decide what we allow it to touch, and what remains off-limits.

The shift apparent in these stories is psychological, not just technological. AI is beginning to participate in thought. At first glance, this might seem like just a heightened level of ‘assistance’. But I think something deeper is happening: private, internal dialogue is becoming externalised, shaped in tandem with a machine. AI is entering the space where we figure things out.

This may not be inherently good or bad. But it is new, and it’s remarkable how naturally youth are adapting to it. Most students I spoke with seem to be navigating this shift with some degree of self-awareness, drawing boundaries and trying not to grow overly dependent on AI. But not everyone will be as reflective. In a plausible future where AI plays a bigger role in our thinking, perhaps the most important skill won’t be technological fluency, but the ability to remain grounded in what we hold on to – the parts of thinking that make us who we are.

What students are asking of AI isn’t so different from what they ask of me. I sit with them through the in-between moments – the murky thoughts, the uncertainties, the things they aren’t ready to say out loud. I ask questions that let them hear themselves more clearly, and help them go from feeling to understanding. Increasingly, AI is stepping into this role too, not because it’s smarter or wiser, but because it’s available. Because it responds without judgment or fatigue. And because, like any good sounding board, it helps you feel like you’re not thinking alone.

I still believe there’s something irreplaceable about the human relationships students form in college – quiet hours spent unravelling the hard things, face to face. But I also see the appeal of this new, frictionless companion. The question is: what kind of presence do we want it to be? The more these students and the rest of us turn to AI for comfort, reflection or advice, the easier it becomes to bypass the slow, messy and deeply human work of connecting – both with others and with ourselves. AI may not replace these relationships entirely, but it could displace them in some ways, making it easier to retreat inward, rather than reaching out. That’s why the question matters. When students knock on my door, I’ll keep listening – the old-fashioned way. Sometimes they’ll seek my voice, sometimes an AI’s. If we’re thoughtful, maybe there’s room for both.