It is well known that artificial intelligence systems ‘hallucinate’, generating confident but false information in response even to straightforward searches. From inventing criminal histories for law-abiding citizens and fabricating case law and policy changes, to making factual errors in solving mathematical problems, hallucinations are a persistent, and sometimes harmful, menace. But unlike most wrinkles in the system that get ironed out over time, AI hallucinations are getting worse.

To understand why they persist, it helps to see them not as acts of deception, but as predictable behaviours of systems built to be fluent. AIs do not ‘think’ like humans; they search, sift and collate, but they cannot critically reflect. Some experts think that hallucinations arise because of so-called overfitting, which is when AIs have been trained so well that they effectively ‘memorise’ information rather than ‘generalising’, which can lead to a form of inflexibility (like arguing with someone ill-informed who insists they are right). Others blame flawed algorithms or bad actors ‘poisoning’ the training data.

However, large language models (LLMs) are just prediction engines: in response to a given prompt, they generate the next most likely word sequence from their data stores. When inputs are incomplete or conflicting, the system still produces an answer because that’s what it has been optimised to do. The coherence is structural rather than reflective: it inheres in the smoothness of a sentence, not in a commitment to the reality it describes, or to its moral valence. AIs lack a mechanism that can robustly hold contradictory information the way that a consciously evaluating mind does, or suspend judgment, or update itself in a way that resembles reflective self-scrutiny. Where there is uncertainty, AIs rush in to fill the gap with plausibility.

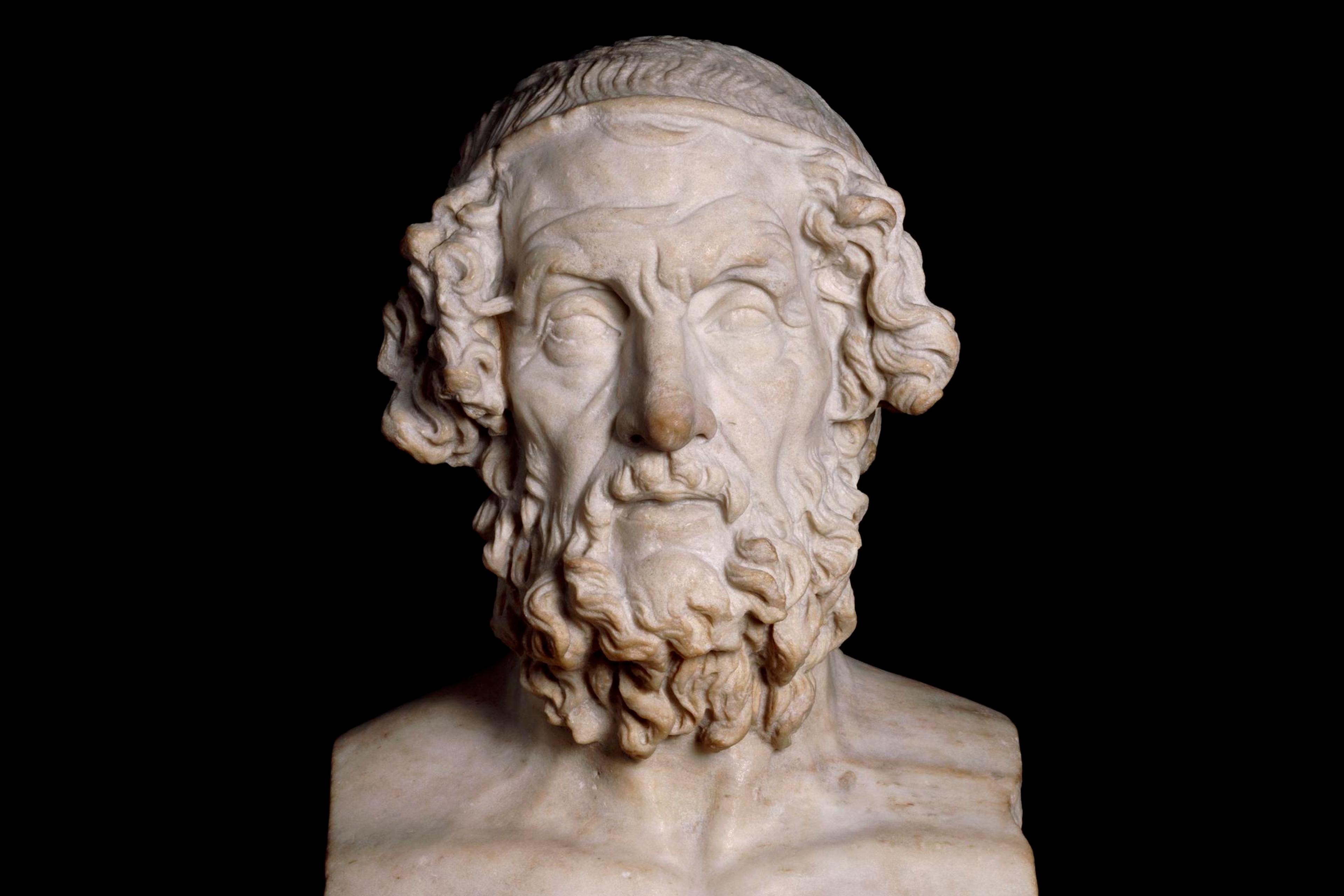

An intriguingly similar behavioural pattern appears in ‘narcissistic confabulation’. Here, too, the system, in this case a human psyche, produces a fluent story that protects its own internal coherence. The analogy is architectural: the point is not to pathologise or dehumanise people with narcissistic traits, who often carry difficult histories, nor to claim that AI is ‘narcissistic’, but rather to cast light on why both humans and machines might generate narratives that feel coherent while remaining unmoored from truth.

Narcissism is a morally loaded term, often used irresponsibly as a shorthand to describe almost sociopathic self-absorption. But clinicians view narcissism as a ‘disorder of self that results in character traits of self-emphasis, grandiose ideations and behaviours that impair relationships’. The narcissistic self is brittle, possibly as a result of developmental trauma or insecure attachments, and it lacks an inner core of stability. To cover up or mask this fragility, the individual may project a façade of confidence and entitlement, and an unwavering (if erroneous, or deeply biased) narrative of reality. The deception is not malicious, but rather a defensive mechanism to protect a sense of self that is constantly at risk of fracturing. When someone with a narcissistic personality disorder feels threatened by uncertainty or doubt, their compulsion is often to project authority.

As the narcissism expert Sam Vaknin explains: ‘In an attempt to compensate for the yawning gaps in memory, narcissists … confabulate: they invent plausible “plug-ins”’ that they fervently believe in. Coherence becomes a defence, used to hide the uncertainty or emptiness that afflicts those with a fragile sense of self – and a crutch, since letting go of a false narrative risks the entire structure of the self coming undone.

While the surface remains polished, the internal check is missing

What constitutes ‘the self’ is a subject of much debate, but even in this contested field experts tend to agree on certain functional hallmarks. A well-integrated self can reflect. A self can withstand contradiction. It can reconcile dissonant information, learn from mistakes, and anchor identity beyond the need for constant external validation. People with a well-integrated self can tolerate holding conflicting ideas such as ‘I love my partner, and I am frustrated with them right now’ or ‘My boss delivered a hard critique and still has my best interests at heart.’ But people with a fragile self want to reconcile or erase contradictions that threaten their (largely projected) sense of internal coherence. And so, for the narcissist, black-and-white thinking replaces nuance, and the opportunity for growth and integration is lost. In short, coherence is paramount, even when it comes at truth’s expense.

Years ago, I was riding in a truck with my then-husband as he was telling a story that became more and more elaborate and improbable as he went on, until I asked: ‘Wait… did this actually happen?’ He paused, then replied: ‘No… but it could have.’ At the time, the answer was merely disorienting. Later, I recognised it as ‘narcissistic confabulation’: the rewriting of reality to protect a fragile sense of self.

This dynamic, in human form, offers a preview of how an AI operates in conditions of uncertainty. In both cases, contradiction is intolerable and plausibility substitutes for truth. Both humans and AIs often double down when questioned, again because letting go of the story threatens to pull apart the primacy of coherence that their architecture (whether psychic or algorithmic) is built to preserve. It’s disarming because, while the surface remains polished, the internal check is missing.

If hallucinations emerge partly from the absence of a self-like structure, one way forward is to design systems that can better tolerate contradiction. This changes the question from ‘Why does the system lie?’ to ‘What would it take for the system to live with “not knowing”?’ This may not mean building sentience but creating architectures that can hold conflicting information without forcing a premature resolution.

One could foresee, for example, how adding persistent memory and self-review mechanisms might allow an AI to flag uncertainty instead of overwriting it. The system would then sit with unresolved inputs until more information arrived, in the same way that a psychologically healthy person is able to say: ‘I am not sure yet.’

LLMs and chatbots reflect back aspects of our own nature with eerie accuracy

The engineering challenge of designing systems that resist the impulse to overwrite inconvenient data is the next hurdle for makers of AI. But exploring how to embed coherence without distortion in AI may also offer fresh perspectives on how to support people living with narcissistic disorders who could benefit from approaches that strengthen the skill of tolerating contradiction. Therapeutic work already aims to help clients develop a more stable internal identity and a greater tolerance for dissonance.

If the greatest risk in confabulation – human or machine – comes less from malice than from emptiness, then cultivating coherence is not sentimental. It is foundational for inspiring trust. In people, this may involve strengthening memory or language to shore up an inner identity that better absorbs discomfort without rewriting history. In AI, it might look like building mechanisms that prefer acknowledged uncertainty over manufactured certainty.

We often talk about the uncanny valley – the discomfort that arises when something appears almost, but not quite, human. The uncanniness in AI is not physical, but psychological: when our LLMs and chatbots reflect back the most brittle aspects of our own nature – and do so with eerie accuracy. In this way, AI acts as a hollow mirror: because it has no sentient self yet it mimics and reflects back the narcissistic compulsion to fill a void with plausible but ungrounded narratives.

What we often fear in AI may not be its difference but its unnerving similarity to the most fragile tendencies we find in human pathology. If we can address the void in machines with architectures that can hold competing possibilities, we may learn something vital about how to shore up a similar capacity in humans. And if in the process we create ways for both humans and AI to better tolerate dissonance, then the reflection returned to us might be less fragile – and more complete.