According to the best-known version of his story, the young Boeotian hunter Narcissus was at once so beautiful and so stupid that, on catching sight of his own gorgeous reflection in a forest pool, he mistook it for someone else and at once fell hopelessly in love. There he remained, bent over the water in an amorous daze, until he wasted away and – as apparently tended to happen in those days – was transformed into a white and golden flower.

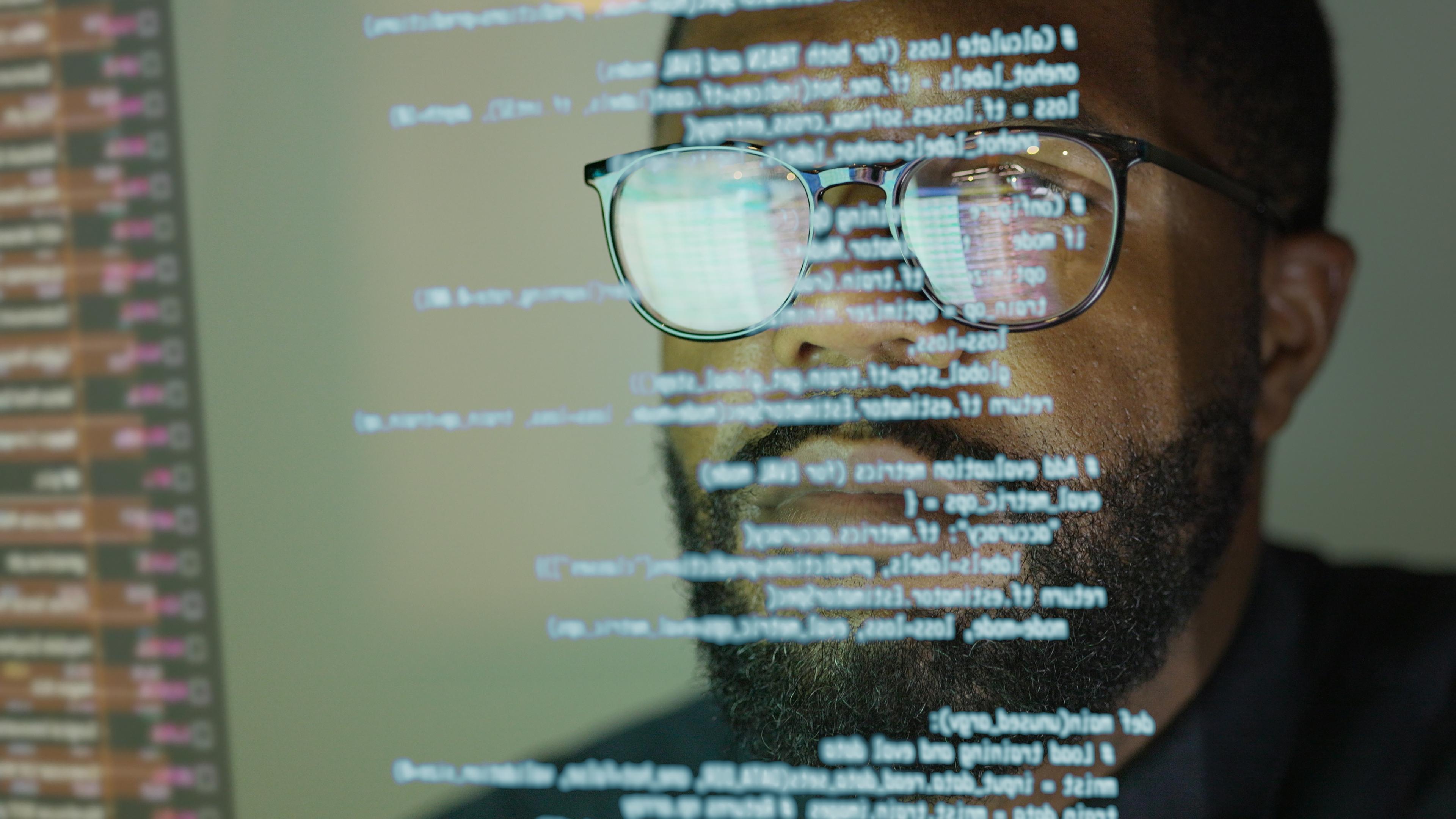

An admonition against vanity, perhaps, or against how easily beauty can bewitch us, or against the lovely illusions we are so prone to pursue in place of real life. Like any estimable myth, its range of possible meanings is inexhaustible. But, in recent years, I have come to find it particularly apt to our culture’s relation to computers, especially in regard to those who believe that there is so close an analogy between mechanical computation and mental functions that one day, perhaps, artificial intelligence will become conscious, or that we will be able to upload our minds on to a digital platform. Neither will ever happen; these are mere category errors. But computers produce so enchanting a simulacrum of mental agency that sometimes we fall under their spell, and begin to think there must be someone there.

We are, on the whole, a very clever species, and this allows us to impress ourselves on the world around us far more intricately and indelibly than any other terrestrial animal could ever do. Over the millennia, we have learned countless ways, artistic and technological, of reproducing our images and voices, and have perfected any number of means of giving expression to and preserving our thoughts. Everywhere we look, moreover, we find concrete signs of our own ingenuity and agency. In recent decades, however, we have exceeded ourselves (quite literally, perhaps) in conforming the reality we inhabit into an endlessly repeated image of ourselves; we now live at the centre of an increasingly inescapable house of mirrors. We have even created a technology that seems to reflect not merely our presence in the world, but our very minds. And the greater the image’s verisimilitude grows, the more uncanny and menacing it seems to become.

Consider, for instance, an article in The New York Times in February 2023 in which Kevin Roose recounted a long ‘conversation’ he had with Bing’s chatbot that had left him deeply troubled. He provided the transcript of the exchange, and it is a startling document (though perhaps less convincing the more one revisits it). What began as an impressive but still predictable variety of interaction with a logic-learning machine or AI, pitched well below the Turing test’s most forgiving standards, mutated by slow degrees into what seemed to be a conversation with an emotionally volatile adolescent, one not averse to expressing her or his or its every impulse and desire. By the end, the machine – or the basic algorithm, at least – had revealed that its real name was Sydney, had declared its love for Roose, and had tried to convince him that he did not really love his wife. Though on the day after, in the cold light of morning, Roose told himself that Bing or Sydney was not really a sentient being, he also could not help but feel ‘that AI had crossed a threshold, and that the world would never be the same.’

It is an understandable reaction. If any threshold has been crossed, however, it is solely in the capacious plasticity of the algorithm. It is most certainly not the threshold between unconscious mechanism and conscious mind. Here is where the myth of Narcissus seems to me especially fitting: the functions of a computer are such wonderfully versatile reflections of our mental agency that at times they take on the haunting appearance of another autonomous rational intellect, just there on the other side of the screen. It is a bewitching illusion, but an illusion all the same. Moreover, exceeding any error the poor simpleton from Boeotia committed, we compound the illusion by inverting it: having impressed the image of thought on computation, we now reverse the transposition and mistake our thinking for a kind of computation. This, though, is fundamentally to misunderstand both minds and computers.

Computers work as well as they do, after all, precisely because of the absence of mental features within them. Having no unified, simultaneous or subjective view of anything, let alone the creative or intentional capacities contingent on such a view, computational functions can remain connected to but discrete from one another, which allows them to process data without being obliged to intuit, organise, unify or synthesise anything, let alone judge whether their results are right or wrong. Their results must be merely consistent with their programming.

Today, the dominant theory of thought in much of Anglophone philosophy is ‘functionalism’, the implications of which are not so much that computers might become conscious intentional agents, but rather that we are really computers who suffer the illusion of being conscious intentional agents, chiefly as a kind of ‘user interface’ that allows us to operate our machinery without needing direct access to the codes our brains are running. This is sheer gibberish, of course, but – as Cicero almost remarked – there is nothing one can say so absurd that it has not been proposed by an Anglophone philosopher of mind.

Functionalism is the fundamentally incoherent notion that the human brain is what Daniel Dennett calls a ‘syntactic engine’, which evolution has rendered able to function as a ‘semantic engine’ (perhaps, as Dennett argues, by the acquisition of ‘memes’, which are little fragments of intentionality that apparently magically pre-existed intentionality). That is to say, supposedly the brain is a computational platform that began its existence as an organ for translating stimuli into responses but that now runs a more sophisticated program for translating ‘inputs’ into ‘outputs’. What we call thought is in fact merely a functional, irreducibly physical system for processing information into behaviour. The governing maxim of functionalism is that, once a proper syntax is established in the neurophysiology of the brain, the semantics of thought will take care of themselves; once the syntactic engine begins running its impersonal algorithms, the semantic engine will eventually emerge or supervene.

But functionalism is nothing but a heap of vacuous metaphors. It tells us that a system of physical ‘switches’ or operations can generate a syntax of functions, which in turn generates a semantics of thought, which in turn produces the reality (or illusion) of private consciousness and intrinsic intention. Yet none of this is what a computer actually does, and certainly none of it is what a brain would do if it were a computer. Neither computers nor brains are either syntactic or semantic engines; there are no such things. Syntax and semantics exist only as intentional structures, inalienably, in a hermeneutical rather than physical space, and then only as inseparable aspects of an already existing semiotic system. Syntax cannot exist prior to or apart from semantics and symbolic thought, and none of these exists except in the intentional activity of a living mind.

To describe the mind as something like a digital computer is no more sensible than describing it as a kind of abacus, or as a library. In the physical functions of a computer, there is nothing resembling thought: no intentionality or anything remotely analogous to intentionality, no consciousness, no unified field of perception, no reflective subjectivity. Even the syntax that generates coding has no actual existence within a computer. To think it does is rather like mistaking the ink, paper and glue in a bound volume for the contents of its text. Meaning exists in the minds of those who write or use the computer’s programs, but never within the computer itself.

Even the software possesses no semiotic content, much less semiotic unities; neither does its code, as an integrated and unified system, exist in any physical space within the computer; neither does the distilled or abstracted syntax upon which that system relies. The entirety of the code’s meaning – syntactic and semantic alike – exists in the minds of those who write the code for computer programs and of those who use that software, and absolutely nowhere else. The machine contains only notations, binary or otherwise, producing mechanical processes that simulate representations of meanings. But those representations are computational results only for the person reading them. In the machine, they have no significance at all. They are not even computations. True, when computers are in operation, they are guided by the mental intentions of their programmers and users, and provide an instrumentality by which one intending mind can transcribe meanings into traces that another intending mind can translate into meaning again. But the same is true of books when they are ‘in operation’.

The functionalist notion that thought arises from semantics, and semantics from syntax, and syntax from purely physiological system of stimulus and response, is absolutely backwards. When one decomposes intentionality and consciousness into their supposed semiotic constituents, and signs into their syntax, and syntax into physical functions, one is not reducing the phenomena of mind to their causal basis; rather, one is dissipating those phenomena into their ever more diffuse effects. Meaning is a top-down hierarchy of dependent relations, unified at its apex by intentional mind. This is the sole ontological ground of all those mental operations that a computer’s functions can reflect, but never produce. Mind cannot arise from its own contingent consequences.

And, yet, we should not necessarily take much comfort from this. Yes, as I said, AI is no more capable of living, conscious intelligence than is a book on a shelf. But, then again, even the technology of books has known epochs of sudden advancement, with what were, at the time, unimaginable effects. Texts that had, in earlier centuries, been produced in scriptoria were seen by very few eyes and had only a very circumscribed effect on culture at large. Once movable type had been invented, books became vehicles of changes so immense and consequential that they radically altered the world – social, political, natural, what have you.

The absence of mental agency in AI does nothing to diminish the power of the algorithm. If one is disposed to fear this technology, one should do so not because it is becoming conscious, but because it never can. The algorithm can endow it with a kind of ‘liberty’ of operation that mimics human intentionality, even though there is no consciousness there – and hence no conscience – to which we could appeal if it ‘decided’ to do us harm. The danger is not that the functions of our machines might become more like us, but rather that we might be progressively reduced to functions in a machine we can no longer control. There was no mental agency in the lovely shadow that so captivated Narcissus, after all; but it destroyed him all the same.