For cancer patients, the best-case scenario after undergoing gruelling radiation and chemotherapy treatments is to be told that they’re in remission, that things look good, but they might not stay that way. When we talk about remission, we leave open the possibility of relapse. We calibrate our expectations with a bit of caution; we might even expect that the cancer will return (even if we hope it might not).

What many call ‘cancer culture’ is underpinned by this hope, that cure might be just around the corner. This is why so many of us raise money by running marathons for the cure, saving yogurt tops, and buying consumer products neatly tied up in pink ribbons. In focusing our attention – and a lot of time and money – on this search for a cure, we risk ignoring the social and environmental causes that lead to cancer in the first place. For example: is it better to buy a car from a dealership that donates some of its proceeds to cancer research, or should we instead invest in green infrastructure and transportation that reduce the levels of carcinogenic emissions into the air we breathe? We might think of this as a form of what scholars call a moral hazard: that in directing our attention toward cures, we’re actively discouraged from addressing the fundamental causes of the problem.

What, exactly, is a cure? We tend to assume that cure is an ending: the end of feeling ill, the end of disease, defect or difference, and, most crucially, the end of treatment. At first glance, this makes a lot of sense. Who hasn’t been laid out by a cold and wished for a quick fix so they could get back to their regularly scheduled lives? For those of us grappling with chronic health conditions, the idea that we could stop taking our daily pills, that we could just be better, is a dream. And isn’t that a dream worth having?

The problem, however, is that cures are rarely so tidy. While there are a limited set of conditions that might be amenable to a once-and-for-all cure, our bodies are almost always marked by our experiences of illness. To be ill is to have one’s body, one’s life, transformed in ways both large and small.

Disability activists and scholars have been at the forefront in thinking about the ethical, political and biological quandaries surrounding cure. To seek a cure is to admit that you have a problem. For many disabled people, the specific configuration of their bodies and minds is not, in fact, the source of their problems. Some have insisted that focusing on cures for various forms of disability further stigmatises disabled people. Moreover, the emphasis on medical cures for disabilities can treat social, infrastructural problems as if they were individual, biological ones.

Here, as in many instances, the details matter. Rather than persist in searching for cures for deafness, for example, we might instead seek to establish and routinise a broader range of communicative norms and forms. At a basic level, this might involve broadening access to interpreters and education in signed languages. More radically, we might also question normative ideas about who counts as intelligible and what counts as proper communication (including for example languages based on touch). Rather than a cure for mobility issues, we might instead seek better, more affordable wheelchairs, wider sidewalks, curb cuts and accessible buildings. We might also work to improve the organisation of contemporary life by pushing for public transportation, universal healthcare and better labour conditions for all. Related arguments have been made by scholars and activists in relation to so-called conversion therapies (to make people cisgendered and straight) and electroconvulsive therapies (to make people sane). Rather than succumb to the tyranny of norms, proponents of these arguments have suggested that we should fight to broaden what counts as normal; instead of trying to transform individuals, we should instead transform society.

Along with the question of whether we should want to be cured, we also need to consider whether a cure is effective. When we push for a cure, we risk putting ourselves through hell for a treatment that might not work or, at least, not work the way we’d want it to work. Is a small chance of cure worth it, if it means spending what are potentially your last few months of life hitched to a hospital bed, in inexorable pain? Or what if your treatment exchanges the symptoms of your illness for new troubles? In the United States, television advertisements for the latest prescription drugs are capped by a terrifying litany of potential side-effects: impotence, incontinence, drowsiness, bleeding, vomiting – the list goes on. Rather than an ending, cure can start to seem like more of an exchange: one set of symptoms for another, a treatment for one condition replaced by new treatments for effects produced by the original treatment, and then additional treatments for the effects of those treatments.

There’s always the possibility that cure will be an ending – that you will finally be done with your disease. As a medical anthropologist, I’ve spent more than a decade studying the social, political and biological forces that shape illness and healing. In 2011, when I began my research for a book on tuberculosis treatment in India, there was a particular refrain that I heard over and over: tuberculosis is an eminently curable condition. If you commit to six, eight, sometimes 12 months of antibiotic treatment, you can come out the other side restored. What I heard less frequently was this caveat: like every other kind of treatment, antibiotics have their side-effects too. The patients I spoke with told me how the drugs made them nauseous and exhausted, how they vomited trying to swallow so many pills. Some of them developed jaundice; others became deaf due to the drugs’ side-effects.

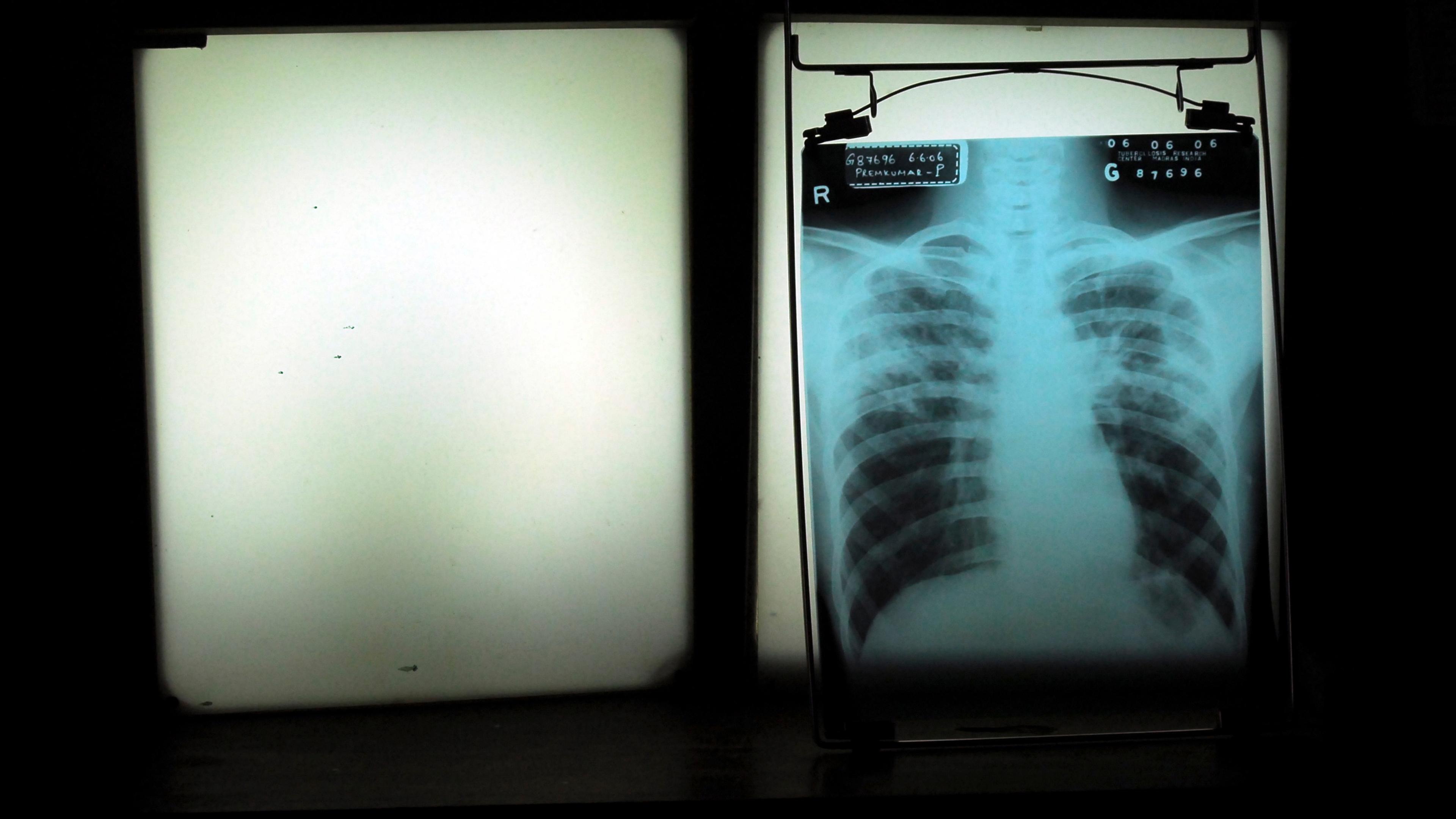

Some of these tuberculosis patients were cured – at least, for a while. But weeks, months, even years later, former patients would return, coughing, to face another diagnosis of tuberculosis, and another round of antibiotic treatment. Across the various hospitals and clinics where I conducted fieldwork, I heard patients insist to their doctors that they had taken their medications as directed, and that they had been declared cured. Many of them even had paperwork – old X-rays, prescriptions and medical charts – attesting to these prior rounds of treatment. Despite the failure of their previous cures to stick, these patients and their families remained optimistic that, this time, things would be different. This time, they hoped, they would be cured once and for all.

The problem of cures that don’t always stick extends far beyond tuberculosis. It’s also not a new problem. What has changed, however, is how we explain why and how cures unravel. One particularly important example in the history of medicine can be found in the ‘talking cure’, as developed by the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud in his Viennese clinic. In 1937, Freud published an essay reflecting on how long analysis should continue, and when it might end. In his essay, he describes the case of a Russian patient, a man who can’t help but spend, down to his last rouble. After extensive therapy, Freud declares the man cured. But, nine years later, the man returns to Freud’s clinic, neurotic and penniless. His cure, it seems, didn’t stick.

What went wrong? The problem, Freud explained, had to do with what he described as the ‘residues of the transference’. In other words, the psychic wound hadn’t been entirely excised. Freud’s Russian patient required intermittent treatment for the next 15 years, as pieces of his past continued to peel away ‘like sutures after an operation, or small fragments of necrotic bone’. Treatment, then, seemed almost interminable – the opposite of an ending.

During my fieldwork in India, I found myself thinking about Freud’s Russian patient. Like the tuberculosis patients I met, he did seem to be cured – for almost a decade. But then, again like the patients I spoke with, he needed to be cured again. Tuberculosis patients can relapse if the bacteria that cause the disease fortify themselves in reservoirs hidden away in the body, waiting to repopulate once the antibiotics leave the system. These drugs can even help to foster the development of drug-resistant bacteria. Former patients can also be exposed to the disease again; as with many conditions, including COVID-19, getting sick is no guarantee of future immunity.

I realised that, if cure was an ending, it was often only one of many. Cure followed cure; ending followed ending. Yet people frequently held on to the hope that this cure would be the one that stuck. This time, they would get better and stay better. It’s a reasonable thing to hope for – especially when the alternative looks like hopelessness, worsening symptoms or death – but it comes at a cost. Some of the patients I spoke with had visited a battalion of doctors, both public and private, and they (and their families) had often spent more money than they had. As debt accumulated, other priorities – rent, food, the education of a son, the marriage of a daughter – were postponed. For these patients and their families, the cost of cure was more than a metaphor.

The problem with cure, then, is that we don’t always know what it is that we’re hoping for, and we don’t always know what we’re getting. When we hold firm to an absolutist logic of cure (as an ending, once and for all, or as a restoration of our bodies to how they used to be), we’re often unprepared for what we actually get, and what our bodies become. This logic of cure also threatens to distract us from what might seem like more fundamental issues of accessibility, quality healthcare and environmental justice. In turning to consider some of these issues, we sometimes find that the question of cure becomes – almost – irrelevant. At the same time, when faced with pain, exhaustion or the possibility of death, there will always be moments when what we wish for is a cure that will truly be an ending, once and for all.