Of all the terms my friends and I use to describe how binge-watching affects our minds and moods, ‘brain-rot’ is the most grimly satisfying. It’s so appallingly evocative of that feeling of mental befoulment that comes with a good, long wallow in the stream of online content, as infinite as it is innutritious. But brain-rot has been with us for centuries. In 1603, the poet Thomas Greene railed against the latest crop of hack writers who brought ‘vnsau’rie [unsavoury] writings to the Presse, / To dull the eares of men’, who consequently suffered ‘swellings of their rotten braine’. In this gustatory analogy, the consumption of ‘vnsau’rie’ materials has a direct, putrefying effect on the ‘braine’ itself. Metaphorical and literal decay are mixed up in an undistinguished mush. From Greene’s backhanded reference to the ‘Presse’, it’s clear what sort of poetry he means. Even at this stage in its history, the printing press had not quite shaken off its association with mass-market literary entertainment.

It’s tricky to make historical comparisons about mental phenomena – feelings, emotions – that seem to recur across very different periods and cultures, even when the exact same words are apparently used to describe them. But the underlying logic of brain-rot, a messy mutual entanglement between brain and culture, endures. In particular, the idea that lower, popular forms of culture might dangerously intermingle with the physical structures of the brain is remarkably persistent. The words ‘highbrow’ and ‘lowbrow’ themselves derive from the Victorian pseudoscience of phrenology, which affirmed that more intelligent people had higher foreheads. As that etymology suggests, the conceptual linkage of brain and culture has shifted over time between metaphorical and literal kinds of meaning, and between each component being causative or symptomatic of the other: do certain sorts of brain create certain kinds of culture? Or vice versa?

In the 21st century, science has applied new methodological tools to these questions. One study by Italian economists in 2019 suggested that children raised in areas of Italy with greater access to Mediaset – a TV network owned by Silvio Berlusconi, specialising in drivelling game shows – ended up with lower general intelligence scores as adults, and were more likely to vote for populist politicians. The study was reported largely uncritically, with headlines such as ‘How Trashy TV Made Children Dumber’, recapitulating the familiar narrative of brains benumbed by garbage. As with so many questions about our inner lives, answers have also been sought in experiments using fMRI brain scans, which track the flow of blood to different areas of the brain as a proxy for cognitive activity. Those experiments have had varying degrees of seriousness, from proper clinical trials to the journalist who asked, in an article for The Washington Post: ‘Is The Bachelor Making Me Dumb? I Hopped In An MRI to Find Out’ (she concluded that the scanner had captured ‘the presence of oxygen-rich blood in angry bits of the brain’ as she watched).

Forays into fMRI experimentation have been called on to support a wide variety of hypotheses. In contrast to the ire of that Bachelor viewer, another widely reported study claimed that watching reality TV might, in fact, stimulate brain activity in areas associated with empathy. These experiments fastidiously control for age, gender, and a host of other potentially confounding variables. But given the crises of replicability and statistical analysis, which have afflicted psychological studies in general and fMRI experiments in particular, it’s hard to escape the sense that these activities are a story-telling practice, reflecting our cultural priors back at us. If nothing else, their frequency and the wide media coverage of their results indicate a public appetite for their narrative: that the boundaries of the mind are porous, and vulnerable to particularly souped-up cultural products.

In the early modern period, this vulnerability was frighteningly literal. In the same year that Thomas Greene fulminated about rotten brain-swellings, a new translation of Plutarch’s Moralia was published, including an essay that advised: ‘How a yoong man ought to heare poets.’ The essay warns of the dangers of poetry’s ‘straunge fables and Theatricall fictions’, which, ‘by reason of the exceeding pleasure and singular delight that they yeeld in reading them, do spred and swell unmeasurably, readie to enter forcibly’ into the mind, and ‘imprint therin some corrupt opinions.’ Here, brain-rot threatens to creep in contagiously, spreading like a cloud of fungal spores, penetrating the boundaries of the mind and leaving an ‘imprint’ there.

As far as we can confidently assert, this account is essentially non-metaphorical. It really was believed that language (among other sensory inputs) had the power to leave a physical ‘impression’ on the brain. The emotional response to literature was powerfully material, too, operating through the excitement of internal passions. In the analogy of Gail Kern Paster, a historian of early modern emotions, ‘[t]he passions operated upon the body very much as strong movements of wind or water operate upon the natural world’, through powerful physical force. In the translated Plutarch, the suggested defence against the emotional influence of ‘straunge fables’ is forcefully literal: ‘let us beware, put foorth our hands before us, keepe them back and staie their course.’

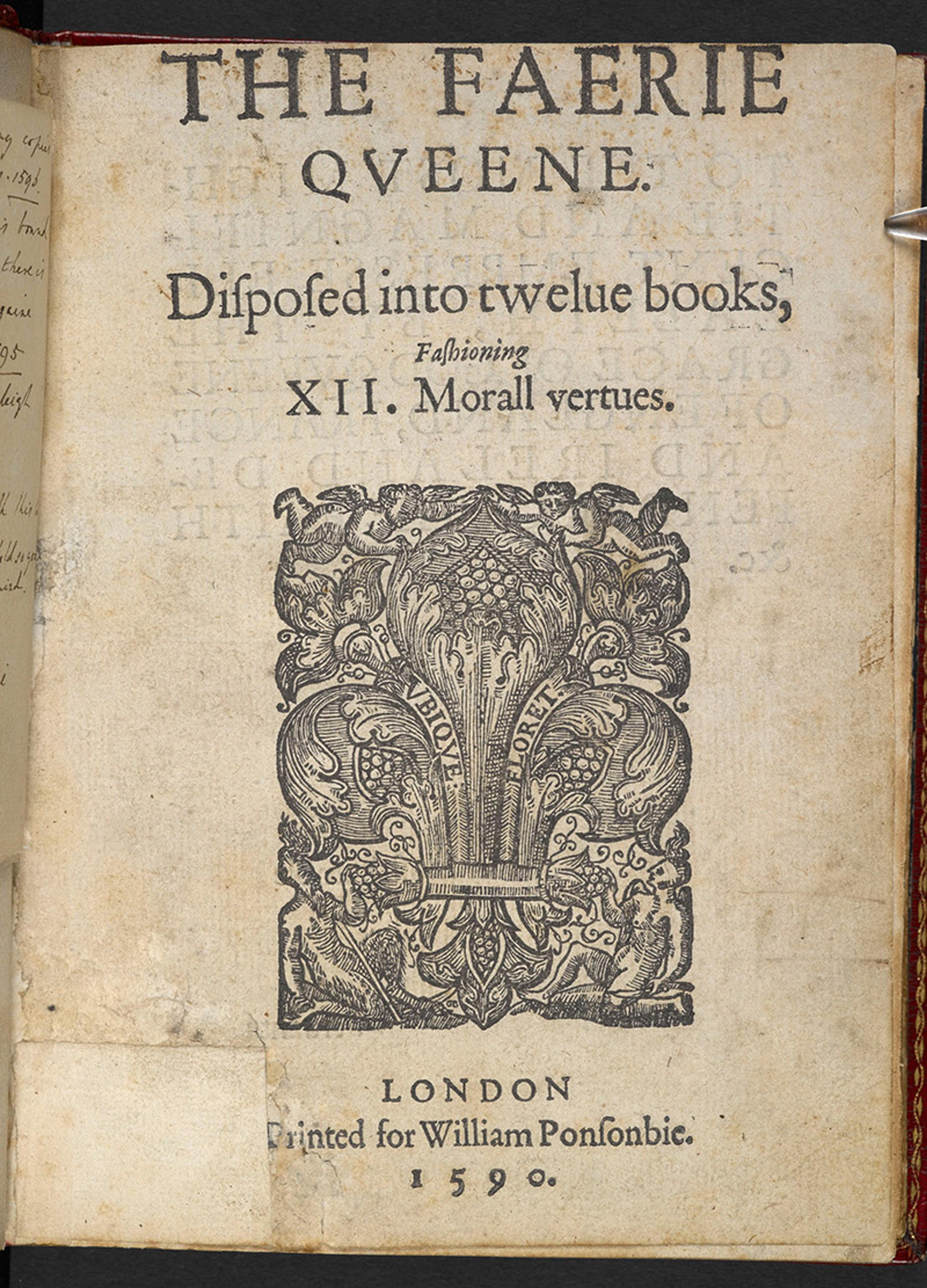

If transhistorical comparisons of emotions are tricky, so too are such analogies of literary genre and cultural status. Still, it’s clear that certain kinds of literature were thought to pose an especially acute threat to the early modern mind. In Thomas Wright’s book The Passions of the Minde (1601), a vivid manual to the early modern psyche, certain ‘obscenous and naughty Bookes’ are singled out for their ability to ‘corrupt’ their readers. Wright is far from alone in this assessment. Criticism of frivolous, unwholesome literature was a commonplace of religious polemic during this period. But which texts, exactly, were being condemned? In his ‘Lectures upon Ionas’ (1594), the future bishop of London John King grumbled that, while Bibles were ‘wont to lie in our windowes as the principall ornaments’, it was ‘Arcadia, & the Faery Queene, and Orlando Furioso, with such like frivolous stories’ that captured the attention of the ‘wanton students of our time’.

Brain-rot: The Faerie Queene (1590) by Edmund Spenser. Courtesy the British Library

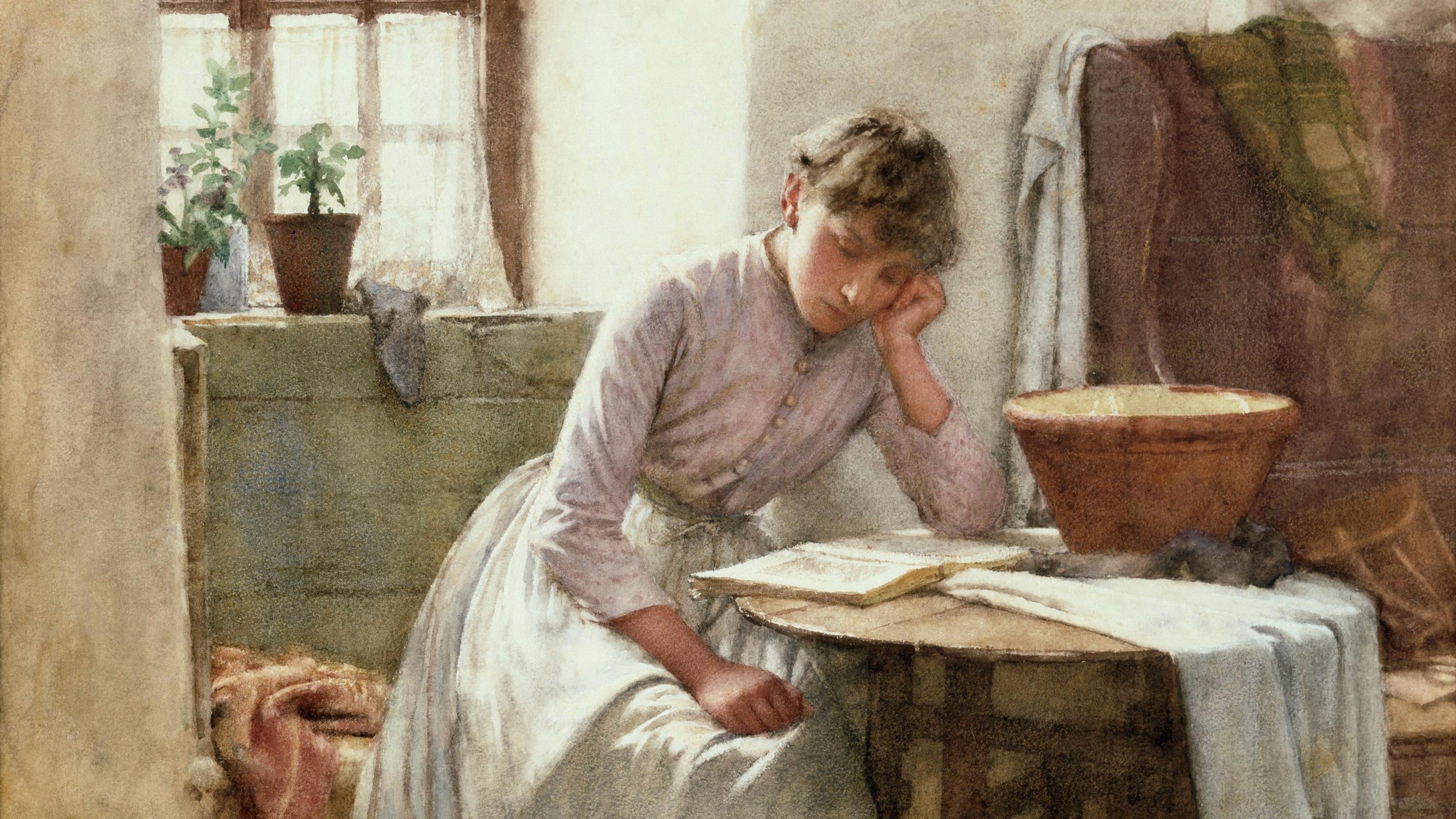

All the titles mentioned by King had been published earlier that same decade: Philip Sidney’s Arcadia (1590), Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene (1590), and John Harington’s 1591 translation of Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (1516). All formed part of what Tiffany Jo Werth, a literary scholar, has called the ‘negative canon’: a ‘strikingly consistent’ group of works that attracted the indignation of the clerical establishment. At the time, these works were referred to as ‘tales’ or ‘fables’, but have since come to be known as romances: lengthy narratives of chivalric adventure and courtly love, combining familiar lore with a dash of continental glamour. Popular and absorbing, romance exerted a dangerously powerful influence on the mind. Women – who, according to humoral medical theory, had cooler, wetter and thus more impressionable minds – were especially susceptible. Giddy female readers of romance were favourite targets for satirists such as Thomas Overbury, who, in his book Characters (1615), depicted a chambermaid who ‘is so carried away’ with a popular romance that ‘she is many times resolv’d to run out of her selfe, and become a Ladie Errant.’

For decades, the poisonous influence of romance on the mind had been articulated in terms of physical disruption and corruption. In 1529, the Renaissance humanist Juan Luis Vives wrote that ‘These bokes do hurt both man and woman,’ as they ‘kyndle and styr up covetousnes, inflame angre, and all beastly and filthy desyre.’ The processes of stirring-up and inflammation described here are not metaphorical, but physical: anger and desire alike are functions of the lower, bodily faculties. The year before, the biblical translator William Tyndale lamented that the masses were forbidden to read vernacular scripture, but permitted to consume ‘Robyn hode & bevise of hampton’ (two popular romance yarns) along with ‘a tousande histories & fables of love & wantones’. Their offence? That they ‘corrupte ye myndes’ with their ‘fylthy’ influence.

In time, the mass stupefaction supposedly incurred by romance-reading was attributed to a grand political conspiracy theory, orchestrated by papist plotters. In 1588, the scholar John Harvey cautioned that the ‘tales’ of King Arthur, Robin Hood and Orlando Furioso were intended ‘to busie the minds of the vulgar sort, or to set their heads aworke withal, and to avert their conceits from the consideration of serious, and graver matters, by feeding their humors, and delighting their fansies with such fabulous and ludicrous toyes’ – not unlike, we might be tempted to suggest, the supposedly addled viewers of Mediaset, fed on mindless pap by shadowy elites with agendas of their own. Such analogies go only so far. But, as Lianne Habinek argues in her book The Subtle Knot (2018) on the early modern mind, we retain a desire ‘to see the brain as this site of a crossing, between the immaterial and the material, between culture and individual body.’ This teeming traffic between mind and world can feel awe-inspiring, or – as with brain-rot – quite numbing. In the end, perhaps readerly feelings tell us less about immutable states of mind, and more about the relative status of different sorts of cultural product at different times. A pinch of context and caution, then, might be useful for neuroscientists and literary critics alike: perhaps the value of culture is not quite all in our heads.