It is midday on a Friday, and I am in a room with about a dozen teenagers at an international school in Oslo, Norway. We are talking about how and why they use TikTok, the digital video-sharing application. The prevailing mood is laid-back: though I am technically a media researcher, and they are technically my research participants, this group of 16- and 17-year-olds are joking around with each other and with me as we chat about the role of TikTok in their everyday lives. It’s a beautiful day – warm and summery – and everyone, including me, is in a fun weekend mood.

‘I dunno, it’s kind of hard to describe what I see on my For You page,’ says one of my participants.

‘Yeah, it’s like…’ another of them pauses, looking for the right word. ‘It’s just mostly brain rot, you know?’

I do not know. This is my first introduction to the term ‘brain rot’. Perplexed, I ask them what it means. Laughing, they describe it as a ‘Gen Alpha word’ that refers to the ‘stupid stuff’ they see on their main TikTok feeds (which are called, for those who aren’t on the app, For You pages or FYPs).

‘It’s stuff that’s dumb, like, it rots your brain. Memes and just random stuff.’ One participant shows me a video on her phone as an example as the others look on. What I see on the screen – an absurd, poorly animated colourful character dancing in the style of a drag queen – looks like nonsense to me, and I say so. This makes them all laugh even harder.

Brain rot: stupid, mindless internet (though mostly TikTok) content. It may seem like a silly bit of slang, but as a researcher I think this new teen terminology can tell us something important about how the younger generation are managing their media lives.

The origins of the term brain rot are not entirely clear. Some websites suggest that it comes from the 2011 video game The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, in which characters can contract a disease known as brain rot. A handful of medical news websites and webpages for private treatment institutions go so far as to suggest that brain rot is a genuine mental health condition that develops as a result of overexposure to online content, with symptoms that include decreased attention span and lethargy.

But despite these questionable origin stories, most sources – including the teenage participants in my TikTok study – agree that brain rot is simply one of many slang terms emergent from and made popular by the current generation of children and young teenagers, Generation Alpha, who were born between 2010 and the present day. ‘Gen Alpha is, like, his little brother’s age,’ explains one of my participants, referring to her 17-year-old friend who has a 10-year-old sibling. ‘But we use the word a lot now. Brain rot, you know?’ Regardless of how it is understood in other places across the web, for these teens it can be defined simply as online content (videos, images, etc) that is so meaningless, banal or dumb that it feels as though it rots your brain.

TikTok is for three things: learning stuff and feeling good about yourself, stalking people, and brain rot

Of course, not all brain rot is created equal. Categories of brain rot have emerged: from the relatively harmless but wildly popular Skibidi Toilet series created by Alexey Gerasimov, which features animations of a human-like head spinning in a toilet, to potentially problematic content such as ‘looksmaxxing’ videos, in which individuals go to extreme lengths to maximise certain aspects of their appearance, or ‘mukbang’, which consists of individuals eating enormous volumes of food while filming themselves. Other types of brain rot include: Grimace Shake, where users on TikTok make videos pretending to have suffered a horrible fate after consuming the purple McDonald’s Grimace Shake, and the Only in Ohio meme, a humorous satire of a conspiracy theory in which unimaginably horrible things happen in Ohio, started after a Tumblr post in 2016 showed a glitching bus station reading ‘Ohio will be eliminated.’

Brain rot as a term covers these as well as all other silly, dumb or time-wasting online content that does not fall into any specific category, such as the video of the dancing animated character my research participants showed me. For them, brain rot is a very clear type of content, but it also represents one of the distinct ways to engage with TikTok.

‘If I want to learn something, I can do that. I actually learn a lot from TikTok. But other times it’s just stupid things and, like, brain rot,’ one participant tells me.

‘Yeah, TikTok is for three things: learning stuff and feeling good about yourself, stalking people, and brain rot.’

In this way, brain rot is what we might call a ‘genre of participation’, to borrow a term from the work of the cultural anthropologist Mimi Ito. On a digital social media application like TikTok, with its endless different types of content, one way of participating is to seek out brain rot and therefore turn off, so to speak, one’s brain. And it’s clear from my research that this type of mindless TikTok video serves an important purpose in the larger ecosystem of the internet.

As a term, brain rot is most definitely not meant to be taken literally. Though the medical websites proposing brain rot as an emergent mental health crisis facing our society may be well meaning, their definition is misguided, at least as far as teens are concerned. The group of 16- and 17-year-olds I work with in Oslo aren’t worried that watching dumb videos on TikTok will really rot their brains. It’s a bit of jokey terminology; one small piece of a broader vocabulary they use to negotiate the vastness of TikTok as well as all the other digital media saturating their lives. As a genre of participation, brain rot is an oasis of calm amid the media chaos.

Moreover, this oasis is a much needed one. My participants tell me they know that brain rot is a waste of time, but they don’t express any genuine fear about it. However, they do tell me about plenty of other things on TikTok and the internet more broadly that make them worried or upset.

Like, Ukraine was a trend for a while, but then Palestine happened and so that’s a huge trend

‘It’s, like, the climate stuff,’ one girl tells me. ‘Or seeing how things are in other places in the world. It’s good to see it because I can, like, learn about it, and about activism against racism and homophobia, but it also makes me feel bad because there’s nothing I can do. I feel like grown-ups don’t care; they are making decisions that are going to ruin everything for us.’ The other participants around the table are unusually quiet as she says this, and I feel them silently echoing her frustration.

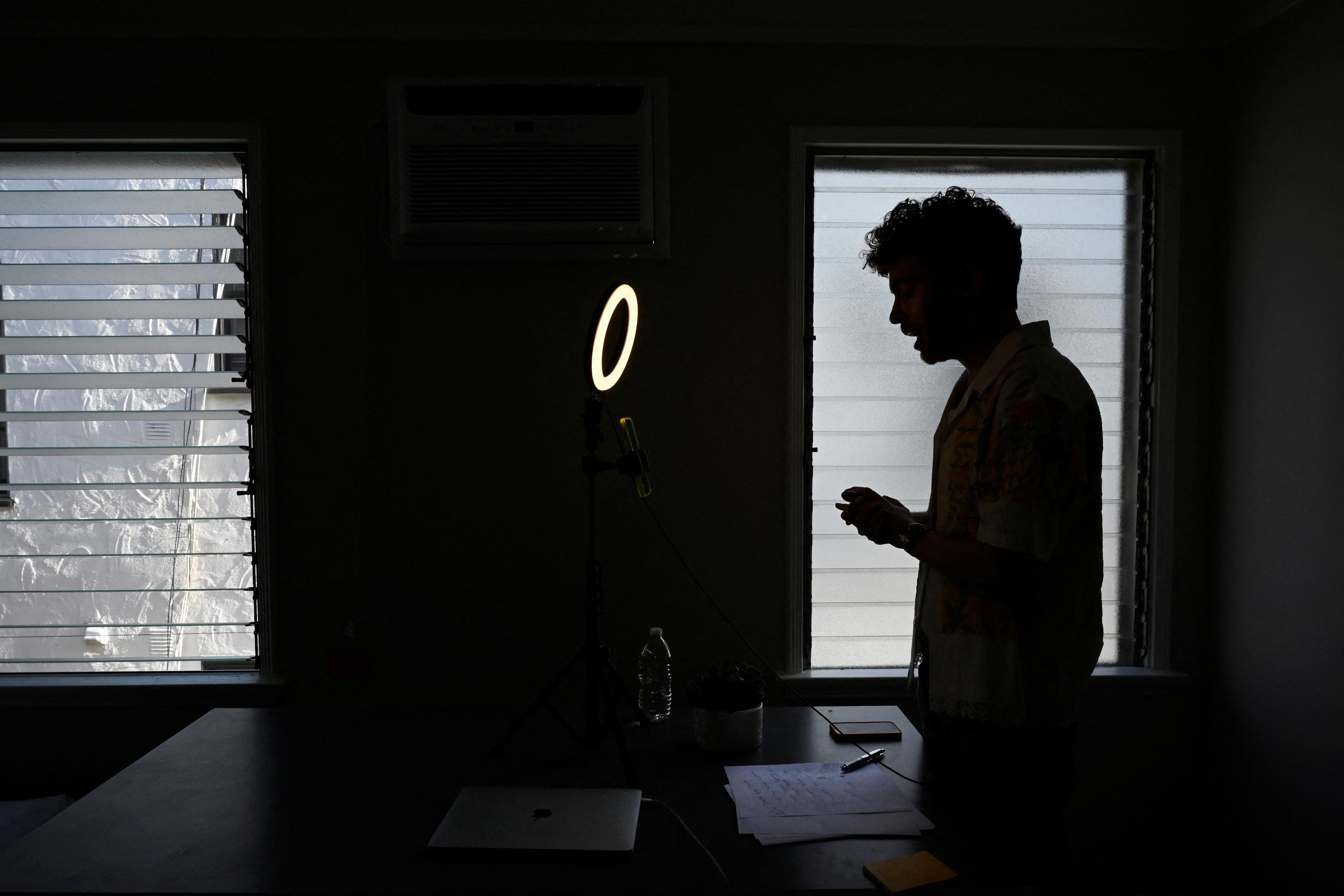

Another boy describes the strangeness of experiencing conflict through a screen: ‘War is a trend on TikTok. Like, Ukraine was a trend for a while, but then Palestine happened and so that’s a huge trend and everyone is pro-Palestine, and now Ukraine… everyone has forgotten about Ukraine.’

These teens also seem keenly, even cynically, aware of the increasing indispensability of these apps and technologies in their lives.

‘I don’t think we could live without them at this point,’ one boy tells me.

‘Yeah,’ says another girl, ‘and in terms of privacy, I know they are taking our information and data and stuff, but that’s just how it is.’

TikTok and digital media aside, this is also just a group of teenagers. They have tests and exams and final assignments to complete, and they are starting to think about university applications. They are extremely worried about their grades, probably because they are being told by nearly every adult they know that what they do right now – the decisions they make this year and the next – will matter for the rest of their lives. They have complex social and personal lives: deepening friendships, nascent romances, family members all around the world, as well as hobbies and interests and goals and ambitions. Their worlds are filled with much anxiety and uncertainty, both onscreen and off.

In this context, for these teenagers, brain rot on TikTok is one tool for tuning out all the stress. It’s a genre of participating in the digital world that enables them to enjoy mindless content, and to turn off their brains for a while. You might say that brain rot is a necessary strategy for managing the particular anxieties of being a teenager at this precise moment in history, fraught as it is with conflict, catastrophe, and predictions of future doom. And while this is by no means the first generation to experience a collision of multiple frightening global events within the space of a decade, this moment in history is perhaps unique in that hundreds of thousands of updates and opinions on said conflicts, catastrophes and predictions of future doom are accessible to anyone anywhere, at any time, with only the swipe of a finger across a screen.

As adults, we can have an unfortunate habit of forgetting our youth as soon as we’ve left it and policing the next generation according to our own expectations. But when it comes to teenagers on TikTok, I think the emergence of the term brain rot suggests that members of this generation possess a highly sophisticated approach for navigating the complexities of their media lives. Much in the same way that teenagers in the 1980s navigated changing economic landscapes through their video games and music video consumption, or earlier generations pushed back against restrictive social values using pirate radio and television, teens today are using TikTok and other digital media to negotiate and make sense of a complex world that is very often designed for adults. In a time of heightened global anxiety and fear, rather than restrict their digital access, we might stand to learn from teenagers about how and why they spend their time on TikTok.

I have narrativised key quotes from my real-life teenage participants, paraphrasing in places in order to protect their privacy rights as consenting informants to an ongoing study.