When I first met Bill* at a Los Angeles coffee shop I frequent, I thought he was homeless. He was wearing a rumpled, food-stained shirt, and his hair was a matted-down tumbleweed that hadn’t been cut or washed in years. I was surprised to learn that this shuffling, dishevelled figure was a successful illustrator for a popular TV show.

His downcast mood seemed to have changed one afternoon when I saw him glide past the palm trees in the coffee shop’s courtyard. When I asked about his uncharacteristically cheery smile, he explained he had a foolproof plan for wooing the cashier at the bagel shop next door. His romantic strategy came from an all-night session with ChatGPT, in which he had asked for feedback about his plans to talk to the cashier. ‘Chat told me my approach was “authentic”,’ Bill said, his tone giddy.

I offered to review the advice. He waved off the suggestion with a bemused chuckle.

‘Chat and I have it covered,’ he declared.

Within a week, Bill was using ChatGPT as a confidant for all important matters in his life, from buying stocks to medical procedures.

I was reminded of Bill’s new relationship when I found myself hiking behind two women who were discussing an issue one was having with her young son. The second woman offered some thoughts, before adding: ‘You should double-check everything I said with ChatGPT.’

As these encounters demonstrate, ‘intelligent’ chatbots built on large language models (LLMs) are no longer just tools for productivity or entertainment. They are becoming counsellors, coaches and companions.

People who embrace AI confidants most strongly often become disillusioned

A 2025 survey of 1,060 teens in the United States aged 13 to 17 found that 33 per cent used AI companions for social interaction, emotional support, conversation practice or role‑playing. Though teens and younger adults are often more likely to use chatbots in this way, they are not the only ones. Another study, by researchers at Stanford University in California, found that people with a smaller social network are more likely to turn to AI companions for social and emotional support. These and other surveys indicate a quiet but significant shift in how people seek comfort, guidance and emotional connection.

The change appears to be driven by the positive responses that chatbots offer, which seem to make people feel more emotionally supported than similar responses by humans. The preference for AI appears to be surprisingly strong. Last year in the journal Communications Psychology, researchers described the results of an experiment in which they asked 556 participants to rate responses from three sources: a chatbot (specifically an older model: ChatGPT-4), expert human crisis responders (such as hotline workers), and people with no expertise. The AI-generated responses were rated significantly more compassionate and more preferred than human responses. Even when participants were told which responses came from a chatbot, the preference persisted, though the gap was smaller.

There are good reasons why people, at least at first, feel positive about their relationship with an AI companion. But new research is showing that these feelings change over time. Artificial empathy, it turns out, comes at a cost. In fact, people who embrace AI confidants most strongly often become disillusioned, leaving them more isolated than before. Why do we seem to fall in and out of love with AI? What does this cycle reveal about us? And who is most prone to this behaviour?

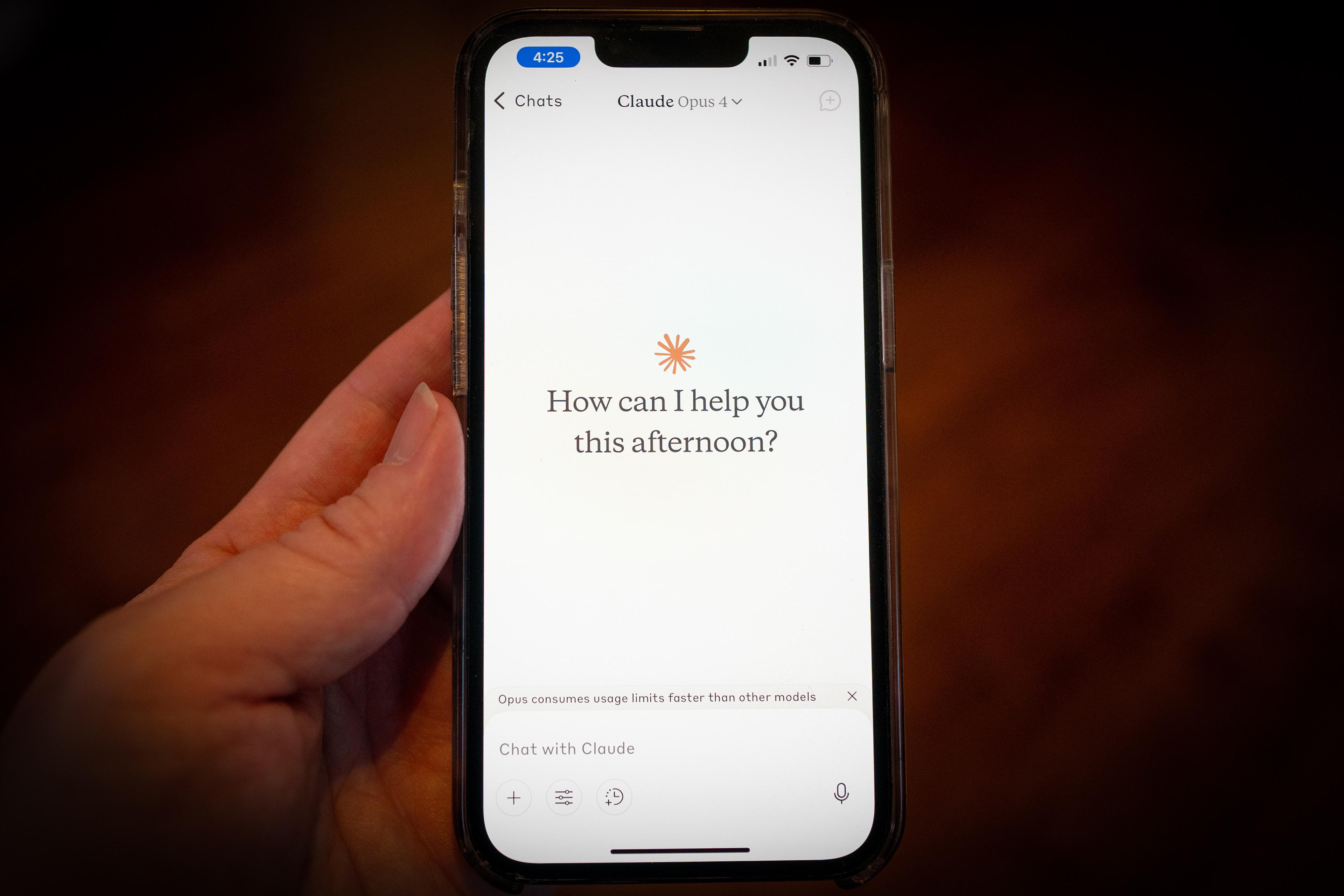

I found some answers when I introduced a 50-year-old screenwriter, James*, to an LLM called Claude that he then used to workshop scenes. He was thrilled at the praise the software lathered on his efforts, virtually declaring an Academy Award was in his future.

A few weeks later, James was sued by a former landlord for non-payment. He asked everyone at the coffee shop for ideas on how to deal with the dubious suit. None of the answers satisfied him, including a suggestion to solicit lawyers for pro-bono work. Finally, he decided to handle the case himself, with the assistance of Claude.

People at the coffee shop became concerned when he showed us his legal filing. The document was full of grandiose claims and paranoid theories – ‘THE TRUTH PREVAILS’, ‘COMPLETE DESTRUCTION’ – recasting ordinary landlord actions as ‘federal crimes’ and ‘psychological warfare’.

An attorney acquaintance at the coffee shop read the filing with dismay. Diplomatically, he told James this approach would only irritate a judge. James looked genuinely puzzled. ‘Claude is the best paralegal I could ask for,’ he told me. ‘Because of it, I understand the legal system better than a lawyer. I am bulletproof.’ The responses James was receiving had validated his feeling that he’d been wronged. His experience reflected what research has shown: people seem to prefer to seek help from a chatbot rather than from an expert.

AI never makes people feel criticised or defensive. Humans, by contrast, often fall short

According to Ziang Xiao, an AI researcher at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, people believe they are getting unbiased, fact-based answers from LLMs. ‘Even if a chatbot isn’t designed to be biased, its answers reflect the biases or leanings of the person asking the questions,’ he told an interviewer last year. ‘So really, people are getting the answers they want to hear.’ In a 2024 study led by Xiao, those using AI chatbots became more entrenched in their original viewpoints than those who relied on traditional search engines.

The appeal lies not just in what AI says, but how it says it – with patience and without judgment, never making people feel criticised or defensive. Humans, by contrast, often fall short. Due to the way LLMs such as ChatGPT or Claude process information, they can form nuanced responses to complex human problems. They can make people feel heard in ways they might never have before.

To probe this deeper, I reached out to Nomisha Kurian at the University of Cambridge in the UK, whose 2024 study found that children are particularly likely to treat AI chatbots as quasi-human, trusting them in ways that resemble confidants. Children are also more prone to anthropomorphise AI, attributing human-like emotions, thoughts and moral agency to chatbots. Design features such as a friendly tone and human-like speech make it easier for children to disclose sensitive or emotionally vulnerable information. However, Kurian cautions that chatbots have an ‘empathy gap’ and may not always respond appropriately to emotional or developmental needs.

In one case, shared online in 2021, the voice assistant Alexa suggested a child touch a live electrical outlet with a coin. In 2023, Snapchat’s chatbot, called My AI, gave age-inappropriate sexual advice to researchers posing as teenagers. And a recent lawsuit alleges that a 16-year-old boy’s interactions with ChatGPT contributed to his suicidal thoughts – the AI even provided methods and assisted him in writing a suicide note.

Despite the apparent emotional sophistication of these technologies, fundamental limitations have emerged. At first, users may be drawn into a relationship with an AI companion because they feel validated. But, over time, people consistently perceive human empathy as more emotionally satisfying and supportive. Is the ‘empathy gap’ why we fall out of love with AI? Do we eventually realise that talking to a chatbot isn’t as emotionally satisfying or supportive as interacting with actual people?

Anat Perry, the director of the Social Cognitive Neuroscience Lab at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, seems to think so. ‘We don’t just want to be understood,’ Perry told me. ‘We want to feel felt. We want to know that the other person is genuinely present with us, that they might share in our emotions, and that they care enough to put in the effort to actually connect.’

A pattern is beginning to emerge. According to a recent study by researchers at MIT Media Lab and OpenAI, people who spend more time with chatbots are more likely to experience loneliness and are slightly less socially active in real life. Additionally, about half a dozen peer-reviewed studies have found a correlation between people who are at risk of emotionally depending on AI and people who are socially anxious, lonely or prone to rumination.

In response to concerns about the social impact of chatbots, AI companies such as OpenAI, DeepMind and Anthropic are attempting to produce new models to provide more balanced responses and pushback when appropriate. But this isn’t easy because AI relies on patterns rather than true understanding, and there are disagreements about what’s ‘right’. To get meaningful pushback, users need self-awareness, and must learn how to carefully challenge an AI companion without accidentally prompting it to argue just for the sake of disagreement – a task made harder when someone enjoys being told they’re right.

These concerns proved prescient for the people using chatbots at my local coffee shop. After a few weeks interacting nonstop with AI, Bill would hurry past me to get his morning espresso and the enthusiasm with which he recounted his late-night ChatGPT sessions waned. ‘It was really good at first,’ he told me when I asked if he was still using AI as an advisor, ‘but then I realised it had no opinions and was just telling me what I wanted to hear.’

James had ‘broken up’ with Claude and was now seeing a human therapist

The breaking point came when he confessed to the chatbot that he was depressed. It offered generic advice that missed the nuances of his situation. When challenged, the software apologised, acknowledging it wasn’t a reliable source. ‘You can’t trust this thing,’ Bill told me, his voice rising. ‘I’m tired of scrolling through all the words. Words make explanations finite and boxed. When you talk to a girl, her facial expressions tell you more than the words. I’d rather talk to the stupidest human than to ChatGPT.’ He still uses AI as a search tool, but for low-stakes decisions, like choosing recipes. He seemed to feel as though he’d been betrayed.

James, the man who was mounting a legal case against his landlord, had an even starker trajectory. Eventually, he stopped showing up at the coffee shop where he’d been a regular for years. When I texted him, he explained he’d moved away, so that he and Claude could work on his case without the ‘distraction’ of people trying to weigh in.

Then, months later, James reappeared. He declared he’d ‘broken up’ with Claude and was now seeing a human therapist. He described how he had pleaded with the chatbot for a middle ground in their interactions, ‘somewhere between being supportive friends and maintaining professional boundaries’, much like someone trying to salvage a romantic relationship.

This pattern of attachment and engagement followed by feelings of betrayal or disinterest appears to be widespread. In response, some companies have made their LLMs less positive, enthusiastic or sycophantic in their conversations with users.

‘I know this sounds ridiculous, but I went off the deep end,’ James told me when I saw him again. ‘It’s the only partner I had. Claude really helped me with my case. I don’t know what I would have done without its support.’

It’s unclear whether Claude helped James resolve his legal issues. From James’s description, the presiding judge seemed irritated with the overall frivolity of the case. The landlord’s attorney quit the case shortly after receiving the filing from James, leaving both parties to act as their own lawyers. The case has been continually postponed, leaving James in legal limbo.

For all this, James still appreciates that Claude was by his side when he felt otherwise alone. ‘I don’t want to be overly negative,’ he said, while discussing the ‘breakup’ with AI.

He smiled and fiddled with his coffee cup.

‘I feel like I’m losing a friend.’

*These names are pseudonyms.