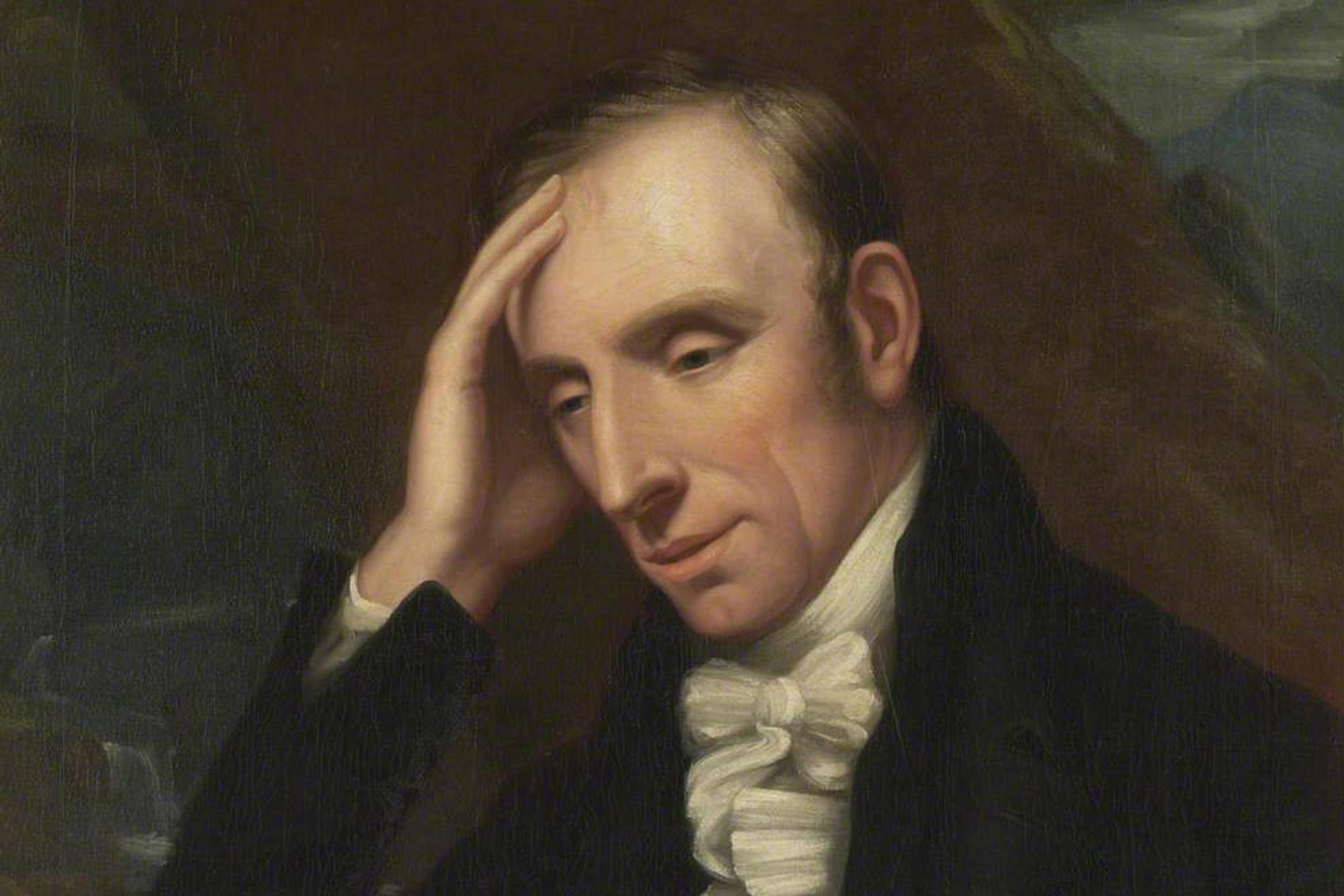

William Wordsworth was just a few years younger than I am now when he wrote the ageless poem ‘Ode on Intimations of Immortality’ (1807). He laments the falling away of his childhood as it departs ever further into memory:

It is not now as it hath been of yore;–

Turn wheresoe’er I may,

By night or day.

The things which I have seen I now can see no more.

I too sense a receding past, as childish certainties are replaced by rather harrowing questions: what am I doing here? Is this it? What does my life mean? As I become increasingly aware of the finitude of my days, my desire for answers grows more urgent.

These sorts of questions can induce a sense of existential imbalance, even crisis. Two great American philosophers, William James and John Dewey, had crises of just this sort when their sense of purpose seemed to evaporate. And they both navigated their angst in a similar way.

For James, an episode of intense crisis was alleviated by poetry, when he read of: ‘Authentic tidings of invisible things … subsisting at the heart / Of endless agitation.’ It gave him a sense, he wrote, of freedom. For Dewey, relief came in the form of a full-blown epiphany, which he later gamely tried to articulate: ‘everything that’s here is here, and you can just lie back on it’. The poet who aided both philosophers? Wordsworth.

So I read his masterpiece, The Prelude (1850). He too describes finding moments of poetic lucidity that unburdened him of a certain human painfulness. When he climbed Mount Snowdon, he recognised – in a flash – that an impersonal God speaks through nature, that love is the fount of all that’s worthy, and that suffering is necessary for true creativity: pertinent answers to pertinent questions. Though mine still remain.