The human desire to communicate with animals is as old as it is universal. It is woven into Indigenous storytelling traditions and echoed in the Old Testament, where humans lived in perfect harmony with animals in the Garden of Eden. It can be found in modern stories ranging from The Jungle Book to The Story of Doctor Dolittle to Urmel from the Ice Age. Today, that ancient dream might be closer than ever, thanks to rapidly evolving artificial intelligence.

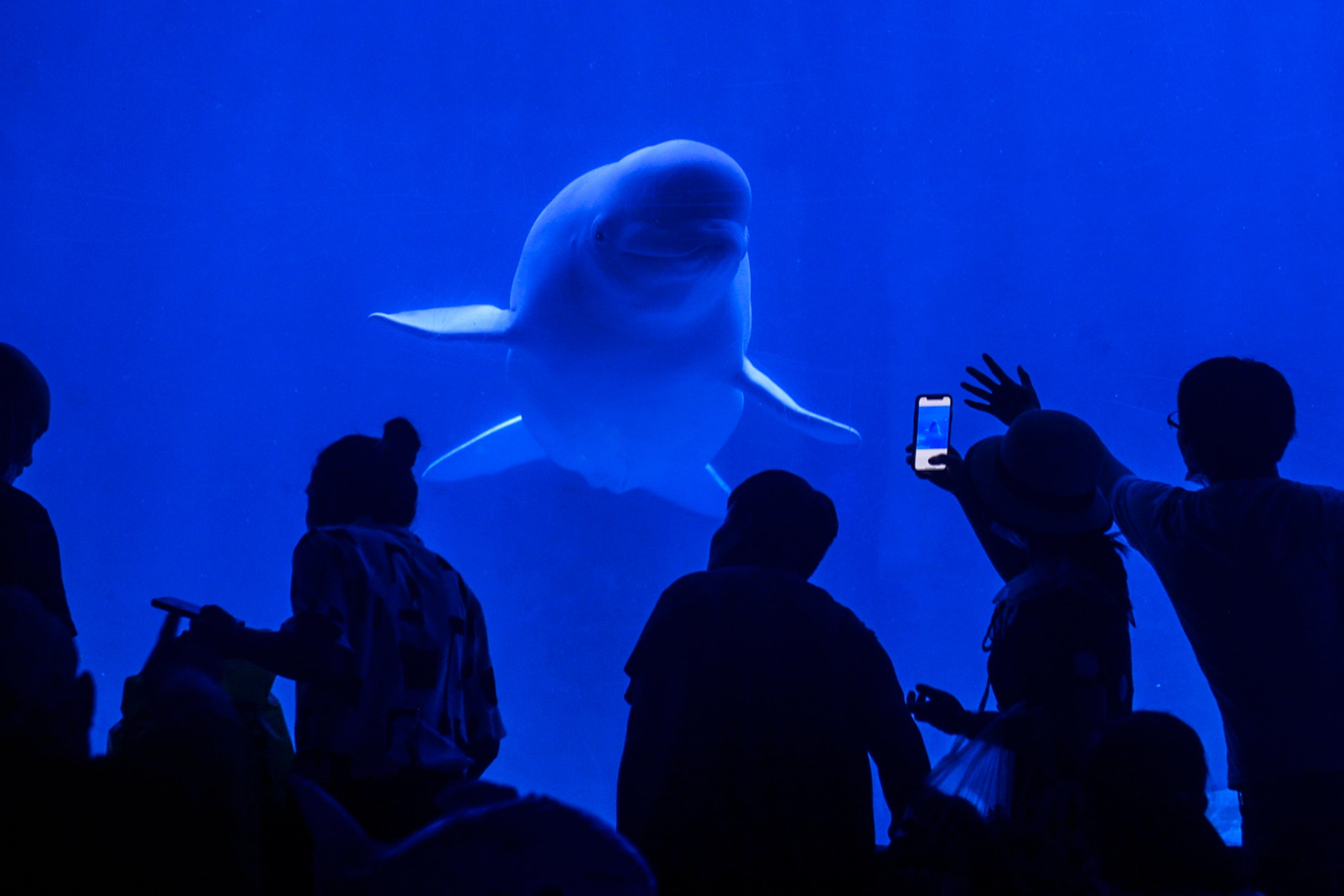

Researchers from the Whale-SETI project used machine-learning technology to communicate with a humpback whale. The team recorded typical humpback whale contact calls – vocalisations used for social connection – and played them underwater via loudspeakers. A 38-year-old female whale named Twain approached, circled the boat, and engaged in a 20-minute exchange, responding to each call with precise timing. She mirrored the turn-taking intervals used by the scientists, suggesting a dynamic and intentional form of communication. We don’t know exactly what she was trying to say – but, in that moment, it felt as if a whale was holding a conversation with us.

This fascinating encounter points towards the potential to engage in multispecies dialogue. AI technologies are used to decode the vocalisation patterns of crows and other social animals, such as whales, elephants and bats. It is increasingly used to uncover the meaning behind their signals, shedding new light on how and what animals communicate. If this technology were ever to be integrated into everyday devices, it might allow curious city dwellers to understand what the birds in the tree next door are so loudly discussing. But, until that day comes, it at least allows scientists to gain a better understanding of these animals.

But should we embrace this possibility? At first glance, these new technologies could be a friend to animals, allowing human beings to expand their knowledge of animals’ emotional and social lives. In northern Spain, carrion crows are known to form stable family groups – an unusual behaviour, given that the species typically lives alone or in pairs. Could this social structure be tied to the way these birds communicate? Meanwhile, the New Caledonian crow has gained fame for its remarkable tool-making abilities. But, even within this species, researchers have identified cultural differences in how tools are crafted across populations. Could distinct vocal ‘dialects’ be part of the explanation? AI could tell us.

It could also be used to understand the lives of animals that are often perceived as less intelligent than crows. In North America, the communication capacities of prairie dogs have been extensively studied by the biologist Con Slobodchikoff. After decades of observation, we now know that prairie dogs can describe their environment in great detail, including calling attention to the human intruders who disturb their peace. Through various alarm calls, prairie dogs can share information about humans’ size and speed and the objects they carry with them. Similarly, cows and their calves use a distinct, individual moo to call each other. Its pitch even varies according to the mother and baby’s physical proximity, getting lower when they are close to each other and higher when they are separated, thus expressing important emotional changes that testify to the strength of their bond. Chickens have been observed ‘speaking’ to their chicks before the eggs hatch.

Animals are not voiceless. They express preferences and desires, form meaningful relationships, and negotiate their environments

If AI were used to develop a more fine-grained understanding of these animals’ ways of communicating, the consequences could be tremendously positive. It could lead us to deeply change the way we have seen and treated them so far – as creatures to whom we have denied language and agency, simply because animal communication had previously been beyond our grasp.

On a practical level, AI could mean improved legal protection and higher welfare standards for animals, as well as significant social changes. Would injuring or killing cawing crows go unnoticed, as is sometimes the case, if we come to realise that the birds are just engaging in a chat among family and friends? Would AI provide us with additional reasons to support higher animal welfare standards for farmed animals, or to consume fewer animal products and by-products, if we come to understand that chickens’ clucks and cows’ moos are like words of love? Would prairie dogs be more protected against habitat loss if, thanks to AI, they could more vividly express their distrust of human intruders? The potential is there. If used wisely, AI could help us better consider animals’ interests, such as their desire to interact with other members of their species or their preference to live free from human interaction.

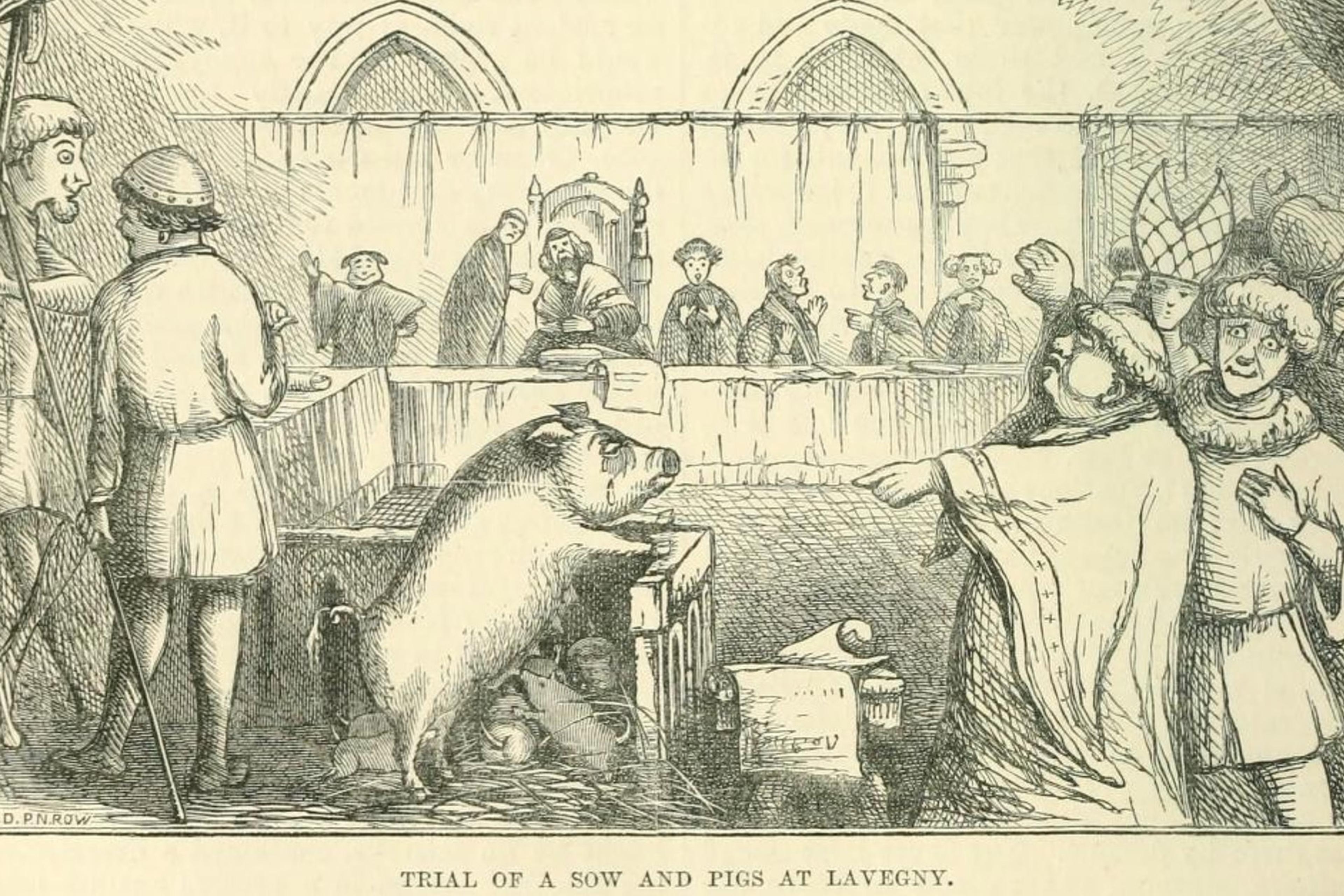

More ambitiously, AI could foster the type of interspecies democracy proposed by several philosophers over the past 15 years. In their book Zoopolis (2011), Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka challenge traditional assumptions about animals’ incapacity to communicate, and argue we should stop seeing animals as passive beneficiaries or victims of human actions. Animals are not voiceless. They express preferences and desires, form meaningful relationships, and negotiate their environments in significant ways. According to Donaldson and Kymlicka, animals are agents whose interests should be considered in political decision-making. In other words, we should pay attention to what animals are trying to tell us.

Could AI foster such an interspecies democracy? It would probably be utopian to think so. More realistically, AI could help us make more informed political decisions in the short term. Before going ahead with projects that could deeply disturb animals’ social and emotional lives – cutting down a tree inhabited by birds, developing untouched meadows, separating mother animals from their children – humans could first listen to what animals have to say, thanks to AI. And maybe this would lead us to change our minds about decisions we thought would not be so harmful.

Furthermore, if AI enables us to understand what animals are saying, we will need to rethink some of our habits, such as confining animals in cages. If we could clearly understand what animals do not feel comfortable with, this could lead to a change in animal welfare laws. While this is the minimum animal philosophers call for, AI for animal communication also comes with the potential to change political decision-making more substantially. For example, legislators could more accurately represent animals’ interests in democratic decision-making processes. Would that mean dogs would have the right to not be left alone for a whole day if they did not want to, or that horses would have the right to spend more time grazing than in stables? Maybe. Maybe AI could let us know if that is what the dog or horse prefers.

Yet the use of AI to communicate with animals comes with risks. Animal communication is an incredibly complex phenomenon. Even more than human communication, it relies on non-verbal cues. AI can help us understand animal communication only if it analyses articulated forms of communication as well as interpreting them correctly in the context of non-verbal gestures. But, as good as AI tools such as language models are at finding patterns, they are often not actually deciphering meaning. And, even when they do appear to get it right, there is no guarantee that they actually have. In fact, even AI developers sometimes cannot fully explain how a model arrived at a certain result – a challenge widely known as the ‘black box’ problem in AI science and ethics.

This raises a troubling possibility: we might end up generating digital animal sounds that seem meaningful to the animals, but without actually knowing what we are saying. As Tom Mustill highlights in the book How to Speak Whale (2022), the sounds of animal communications probably are ‘the glue that holds their cooperative lives together – vital in keeping close, hunting, navigating, mating, and protecting one another.’ Exposing them to digitally generated sounds that irritate or confuse them could interfere with the culture of an animal population that has evolved over hundreds of years. What consequences could that have for the habit of Spanish carrion crows to form family bonds, the practice of prairie dogs to describe their environments in great detail, or the intense bonds between cows and calves? We do not know, and it may not be worth finding out.

If we could finally hear animals as communicative beings, we would no longer view them as passive figures in our world, but as agents within it

Avoiding the most serious risks by refraining from exposing animals to irritating sounds may seem like a safeguard, but it is not sufficient. Even if we succeed in generating animal sounds that convey accurate meaning and elicit reliable responses, the potential for misuse remains high. Such technologies could be weaponised to deceive animals using their own modes of communication, ultimately enhancing the efficiency of hunting and poaching rather than benefiting the animals. The consequences of these practices are ethically troubling. Animals suffer from hunting and poaching not only physically but psychologically. Except in cases of subsistence hunting, such suffering cannot be justified.

Moreover, several philosophers find it plausible that animals, too, wish to continue living. Among them, the philosopher Martha Nussbaum, in Frontiers of Justice (2006), argues that animals have an interest in developing their species-specific capabilities – an endeavour that necessarily requires continued life. The philosopher Mark Rowlands emphasises in Animals Like Us (2002) that many animals have future-oriented interests, such as specific expectations, and therefore maintain a strong interest in continuing to live. If there is any chance that our newfound ability to communicate with animals could diminish their chances of living the fullest life possible, we should go to great lengths to ensure that AI technologies are used only to benefit animals.

How can we make sure that AI does increase the wellbeing of animals instead of depriving them of a life worth living? A realistic solution is to adopt a code of moral principles that will steer corporations in the right direction. These principles must be specific enough to ensure that important values – such as animal welfare, transparency, accountability and neutrality – are respected. We wish to put forward three principles as a starting point.

Principle 1: AI should not be implemented to benefit activities or industries that systemically overlook animals’ interests in avoiding suffering and continuing to live.

Principle 2: Data on animals’ vocalisation patterns should be available to the public, especially decision-makers.

Principle 3: Governments and corporations should consult independent biologists and animal cognition specialists before developing or using language models. This would ensure that AI would not have negative effects on animals, or that these risks could be mitigated.

With these principles in place, AI could benefit animals by shedding light on the complexity of their emotional, cognitive and social lives. Yet the most profound impact of AI-mediated communication might not be regulatory, but existential. If we could finally hear animals as communicative beings, we would no longer view them as passive figures in our world, but as agents within it. Animals such as whales, crows, cows, chickens and prairie dogs would no longer be seen as mute beings, but as interlocutors with preferences of their own. If humanity’s ancient dream of directly communicating with animals finally comes true – or at least very close – we can envision a future in which humanity defines itself not by its separation from other animals, but by its entanglements with them, leading to more respectful human-animal relations and the willingness to listen to our fellow creatures.