Across all kinds of jobs and workplaces, companies are swiftly adopting artificial intelligence in the name of efficiency. The typical business rationale behind the adoption of AI-driven technologies is that they help to identify wasteful activities, or allocate resources more effectively, or otherwise streamline work processes in the service of maximised productivity. AI software is used to optimise supply chains, to reduce bottlenecks, to identify and reward workers for behaviours aligned with organisational goals, and to predict outcomes that can drive firms toward desirable practices in their quest for profit.

Yet many of these technologies rest on a fallacious premise – that these tools save time and effort. In practice, a more accurate assertion is that while these technologies appear to eliminate efficiencies, they often don’t do so. Instead of reducing labour, cost or risk, we can better understand AI technologies as reallocating these burdens from firms onto workers. In so doing, AI may appear to serve the bottom line – but it does so not through labour saving, but the distribution of extra burden onto workers.

Here are a few examples of what I mean.

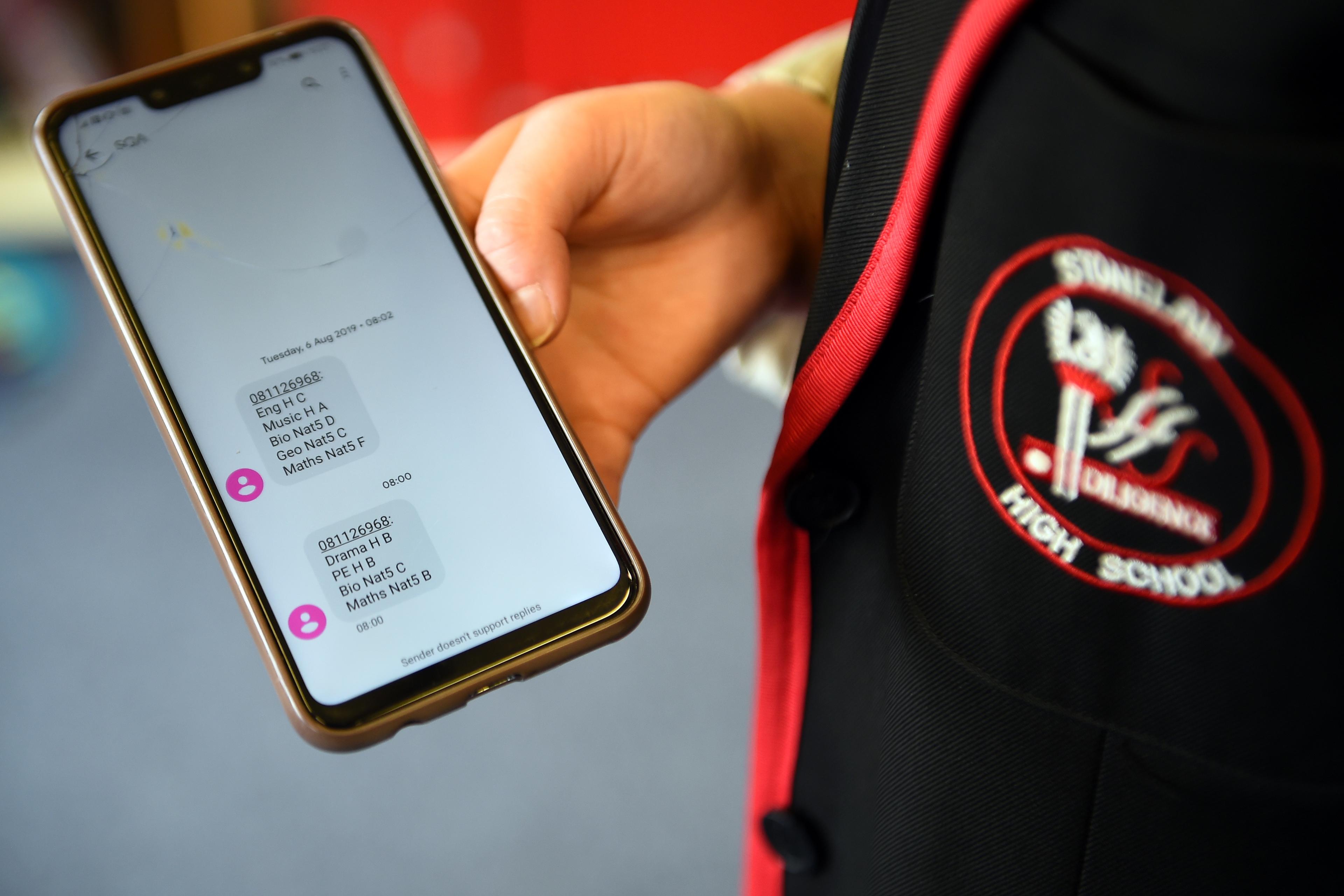

Across many industries and workplaces, workers’ productivity is increasingly tracked, quantified and scored. For example, a recent investigative report from The New York Times described the rise of monitoring regimes that surveil all kinds of employees, from warehouse workers to finance executives to hospice chaplains. Regardless of the quite different kinds of work, the common underlying premise is that productivity monitoring counts things that are easy to count: the number of emails sent, the number of patient visits logged, the number of minutes that someone’s eyes are looking at a particular window on their computer. Sensor technologies and tracking software give managers a granular, real-time view into these worker behaviours. But productivity monitoring is rarely able to measure forms of work that are harder to capture as data – such as a deep conversation about a client’s problem, or brainstorming on a whiteboard, or discussing ideas with colleagues.

Firms often embrace these technologies in the name of minimising worker shirking and maximising profit. But in practice, these systems can perversely disincentivise workers from the real meat of their jobs – and also results in them being tasked with the additional labour of making themselves legible to tracking systems. This often takes the form of busy work: jiggling a mouse so it’s registered by monitoring software, or doing a bunch of quick but empty tasks such as sending multiple emails rather than deeper but less quantifiable engagement. One likely result of AI monitoring is that it encourages people to engage in those sometimes frivolous tasks that can be quantified. And workers tasked with making their work legible to productivity tracking bear the psychological burdens of this supervision, raising stress levels and impeding creativity. In short, there’s often a mismatch between what can be readily measured and what amounts to meaningful work – and the costs of this mismatch are borne by workers.

As more data-driven metrics are built by default into office tools and software, they also can have the effect of locking down channels where workers might organise or talk among themselves about workplace reforms. While these dynamics have been ramping up for a long time, the pandemic has accelerated them as employers look for ways to control remote workers and worry about shirking.

In my new book, Data Driven: Truckers, Technology, and the New Workplace Surveillance (forthcoming in 2023), I show how workplace monitoring technologies are affecting long-haul truck drivers in the United States. The geographically distributed, mobile nature of truckers’ work has meant that they have long been able to maintain a significant degree of autonomy over how they conduct themselves day-to-day – much more so than other blue-collar workers have. These new technologies are changing the experience of trucking work, however, in significant ways.

Truckers find themselves increasingly monitored by systems that record myriad dimensions of how they do their work. The technologies record how fast they go, how long they drive, whether they brake too hard, how much fuel they use and how fatigued they are. Some of these systems use AI-augmented cameras or wearable technologies to monitor truckers’ eyelids, heart rates and brainwaves. Companies often impose these technologies in the name of safety, arguing that gathering such data will prevent truckers from driving recklessly, or will help managers ‘coach’ drivers not performing according to a firm’s standards. Yet digital monitoring systems can in fact make public roadways less safe by removing flexibility from truckers’ work and driving veteran drivers out of the industry. These tools again disproportionately burden workers, infringing on their bodily privacy and occupational autonomy, while employers benefit from fleet-wide analytics and amass valuable data on truckers’ activities.

The technology also shifts burdens of time and labour to workers in the form of algorithmic staffing and scheduling. In retail and food service, work schedules are increasingly determined by just-in-time staffing algorithms. These systems draw on real-time customer traffic and sales data, among other things, to generate ‘dynamic’ schedules for workers. A dynamic schedule can mean shifts that are assigned with very short notice, irregular and fluctuating numbers of hours per week, and microshifts that are sliced and diced into small chunks where more demand is expected. Such erratic scheduling appears efficient from the perspective of the firm: the company wants to predict and avoid the risk of either overstaffing or understaffing a shift, either of which can undercut profit. It’s a different matter for workers. A good deal of research shows how these systems can make it difficult for workers to earn a steady income, or work a second job, or take classes, or care for their families. In fact, these harms even cross generations, affecting the outcomes of the children of people who work under these conditions. The risk of fluctuating customer demand – which used to be borne by the company – is not eliminated by AI tools, but instead gets offloaded onto employees. It gets hidden because it’s been shifted to – and forced onto – low-wage workers, who are the least powerful players in the ecosystem.

It is important to understand, then, that AI is fundamentally a reallocator of burdens from firms to workers. Any effective policy response must target this dynamic and return some costs back to firms. There are a few possibilities. We might curtail some of the harms of workplace AI by directly regulating the technologies at issue – as, for example, a number of states and cities have done via ‘fair scheduling’ laws. These laws attempt to mitigate the instability of predictive scheduling algorithms by ensuring workers have sufficient notice of their schedules, and are compensated if shifts are cancelled or changed at short notice, among other provisions. Similarly, some EU member states have made rules that constrain the use of certain types of invasive monitoring (such as GPS tracking) in the workplace. Other strategies might involve recalibrating pay regimes to ensure workers are fairly compensated for the true amount of work they do; for example, recently introduced legislation would reverse long-haul truckers’ exemption from the Fair Labor Standards Act, which prevents them from receiving overtime pay for their work. And we might find promise in policies that protect the capacity of workers to bargain collectively: the US Department of Labor has recently taken aim at workplace surveillance technologies that could interfere with workers’ abilities to talk confidentially among themselves about unionisation. Together with other protections, strategies like these show promise for tipping the scales back a bit in order to protect labour interests and worker dignity in the AI-mediated workplace.