For most of my 20s, I couldn’t brush my teeth, ride public transit, or take a walk without listening to a podcast or audiobook. Silence, I thought, was a waste of time.

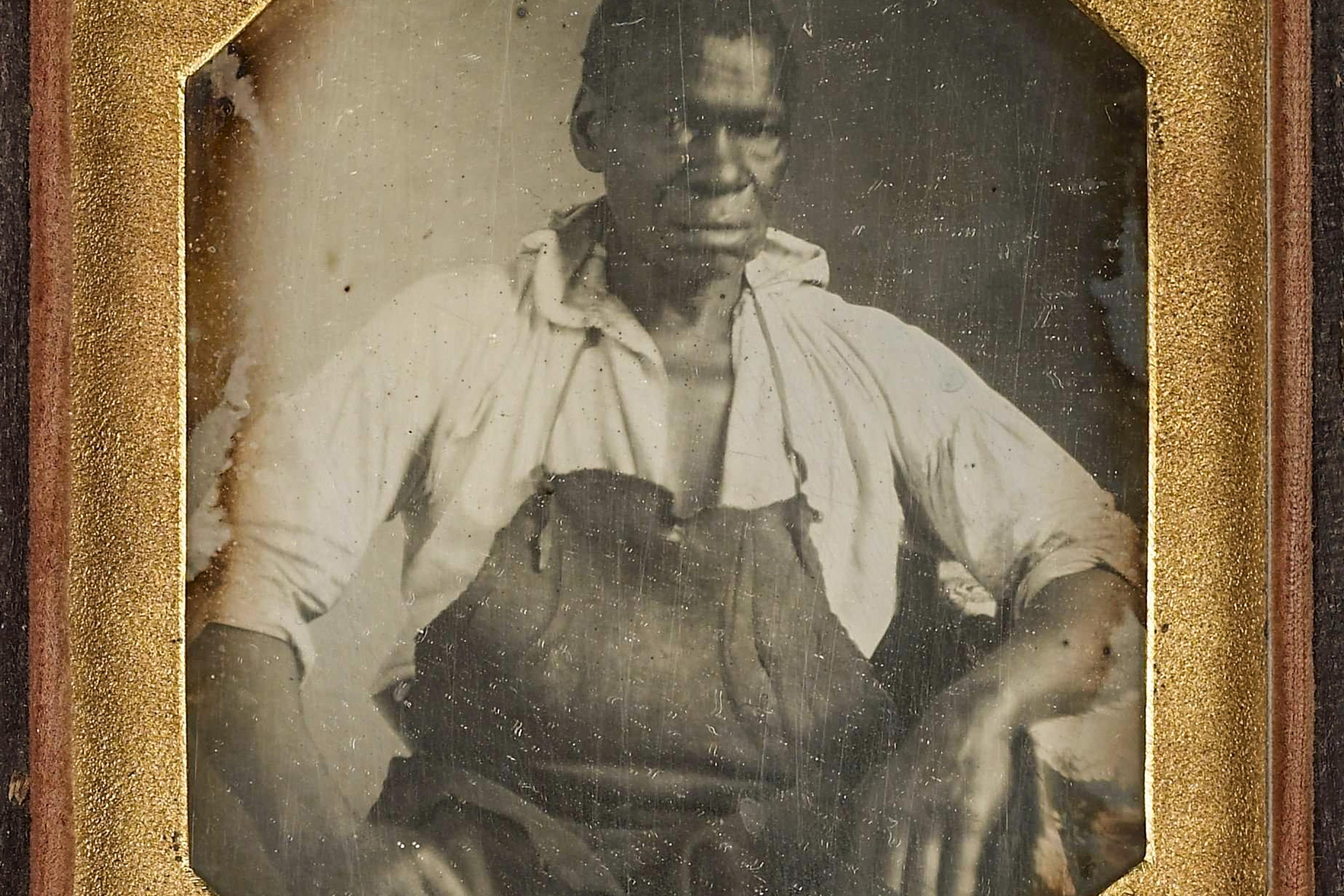

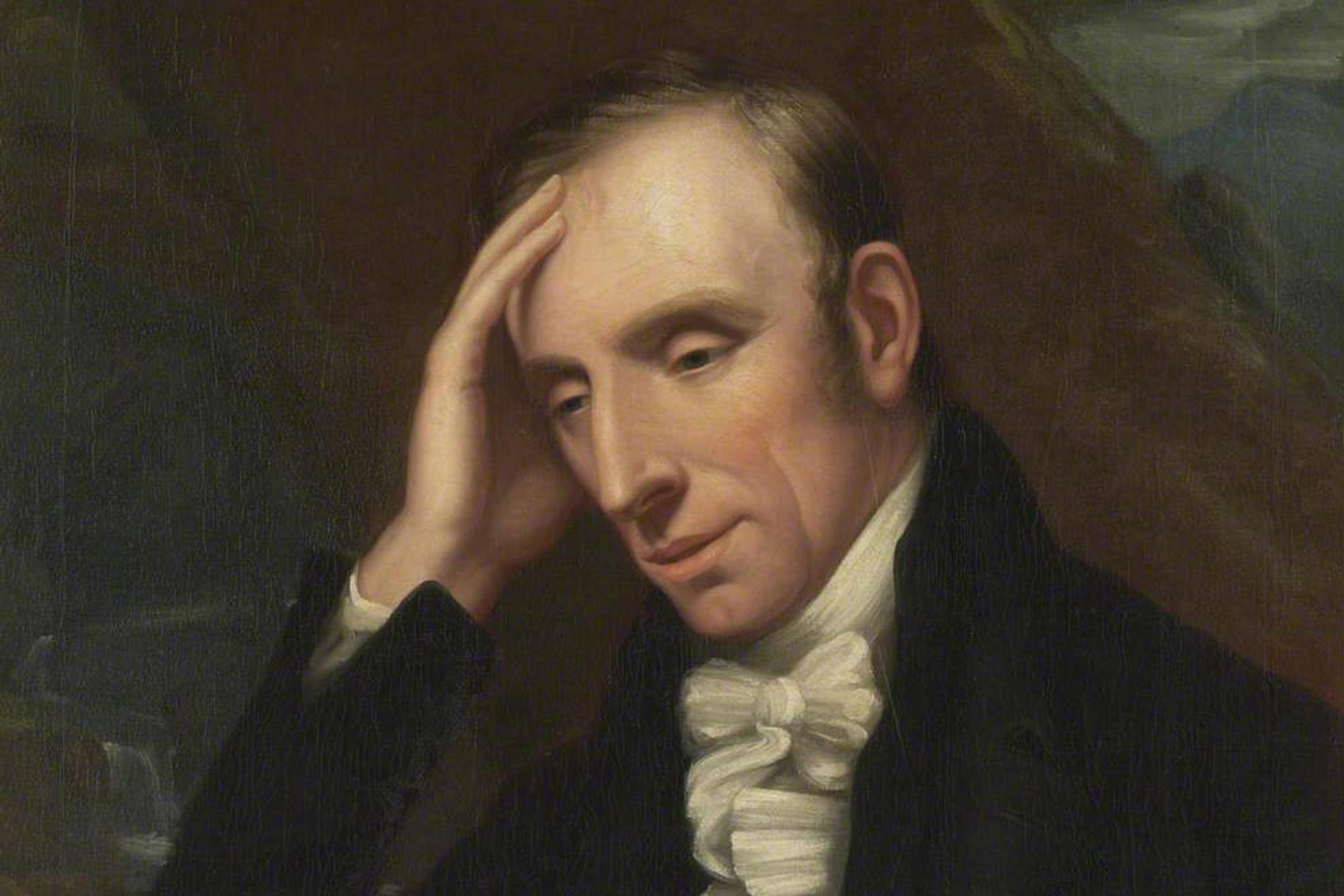

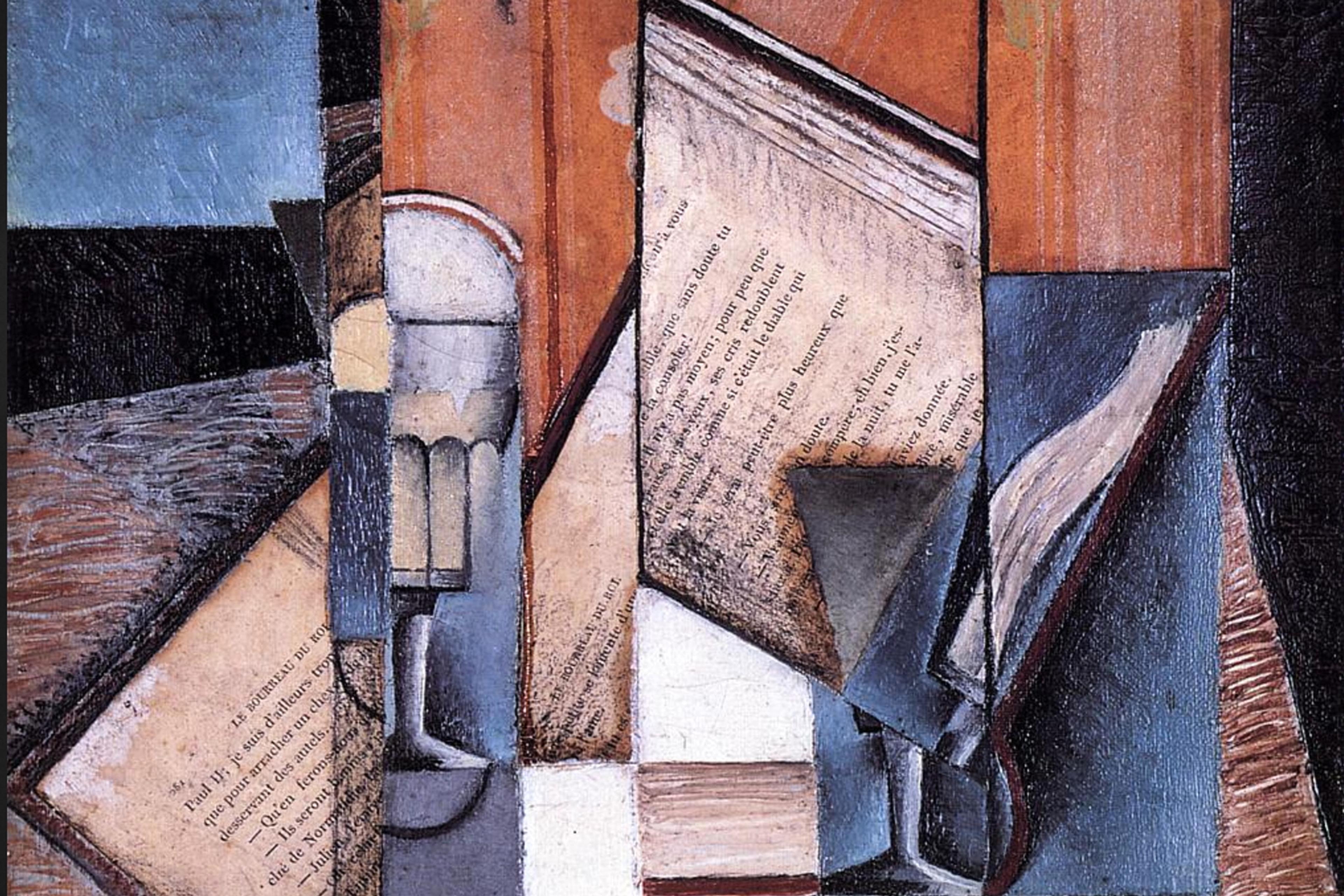

But since reading All the Beauty in the World (2023), I’ve been reconsidering my relationship to dull, seemingly empty moments. In the book, Patrick Bringley recounts his decade among the watchful guards of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Standing in the Met’s echoic halls for hours on end, day after predictable day, he found that, over time, his relationship to the work slowly changed. Initial enchantment with the art gave way to boredom – and then, enlightenment. He surrendered to the ‘turtleish movement of a watchman’s time’, stopped thinking about how much of his shift was left, and let the hours drift.

I think about Bringley’s experience when I have to engage in any long, monotonous task. It might be waiting in line or on hold, vacuuming, folding laundry, or chopping vegetables for dinner. I resist the urge to fill the time with music or podcasts and strive instead for what Bringley calls a ‘princely detachment’ from time, finding the luxury and nuance in the moment.

Bringley noticed patterns in the different kinds of Met visitors. Hanging up my laundry, I notice patterns in how different articles of clothing tend to wrinkle in the wash. Bringley developed an appreciation for artworks that he initially ignored. I pay finer attention to the unique composition of facial features on the faces of people I stand in line with. I am learning, I think, to appreciate the little things.

Of course, it requires constant practice to find the peace and richness in these stretches of time. But your reward comes, Bringley says, when an hour no longer feels an hour long, and you ‘hardly remember how to be bored’.